The short history of the Advanced Photo System film camera

APS was meant to give film photography a new lease on life, but it soon became clear that digital imaging was the future

Like it or not, the camera phone represents the culmination of what the photographic industry had been trying to achieve for the best part of 150 years. It’s a compact device that’s easily carried anywhere and delivers an acceptable result in most situations without requiring anything more than the press of a button. Of course, it helps that you can now essentially run your life with your smartphone, but the photography element was where the compact point-and-shoot camera was always heading… minimum fuss, maximum reward.

There was a good century of development from rollfilm to ever smaller format films packaged in various cassettes and cartridges – 35mm, 126, 110 and Disc – designed to make for easier handling with fewer mistakes. Each succeeded to some extent, but there was always room for improvement and so, in the early 1990s, work began on the most ambitious cartridge-based film system ever devised - the Advance Photo System.

As ever, the Advanced Photo System was driven by Kodak, which had been at the forefront of popularizing photography since devising the original box camera in the late 1880s. Looming on the horizon was ‘electronic photography’ which had already manifested itself with the still video camera – mostly championed by Sony, but plenty of others dabbled with prototype systems. While the analog approach was inferior to film in many ways, it made the point about potential conveniences, and work was well underway on digital technologies that would better exploit them.

Nevertheless, within the photography industry at least, it was still believed that film was the way ahead, but with a system that also had to deliver more conveniences than 35mm – the small format that had set the benchmark for image quality. So Kodak was joined by Fujifilm, Canon, Nikon and Minolta – a powerful group of leading Japanese photo companies – in the Advanced Photo System which, inevitably, quickly became known simply as ‘APS’.

If APS had arrived 10 years earlier, it would have been a very different story, but history and technology conspired against a system.

With 35mm continuing to gain in popularity and affordability, and digital imaging definitely not going away, it’s a little surprising APS actually ever happened, especially as it wasn’t ready for launch until early in 1996. In fact, APS was unveiled to the world on 1 February, but on 3 June – just four months later – Kodak launched its DC20, the first truly compact and comparatively affordable digital camera that, ultimately, helped sealed the fate of film. However, this didn’t stop just about everybody jumping on the APS bandwagon and, after launch, the system was joined by Agfa, Hanimex, Konica, Olympus, Pentax, Panasonic, Yashica, Contax and even Leica.

In fact, the only major camera brand that didn’t sign up to APS was Ricoh which, by that time, was enjoying huge success with its ultra-slim 35mm R1 (1994) and GR1 (1996) compacts, and was already looking ahead to the digital era with its radical RDC-1 (also 1996).

Easing The Load

Over the years a number of features had been added to 35mm to make it more goof-proof, including DX (Direct eXchange) coding for automatic film speed setting, drop-in film loading and film prewinding which meant all the exposed frames were safely in the cassette should the camera be opened accidentally. The latter two are, of course, camera based and, in reality, were not widely adopted, so film loading errors – which inevitably resulted in lost pictures – continually topped the lists of consumer complaints about 35mm photography and, consequently, were seen by the industry as inhibiting growth in the then-lucrative point-and-shoot sector.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

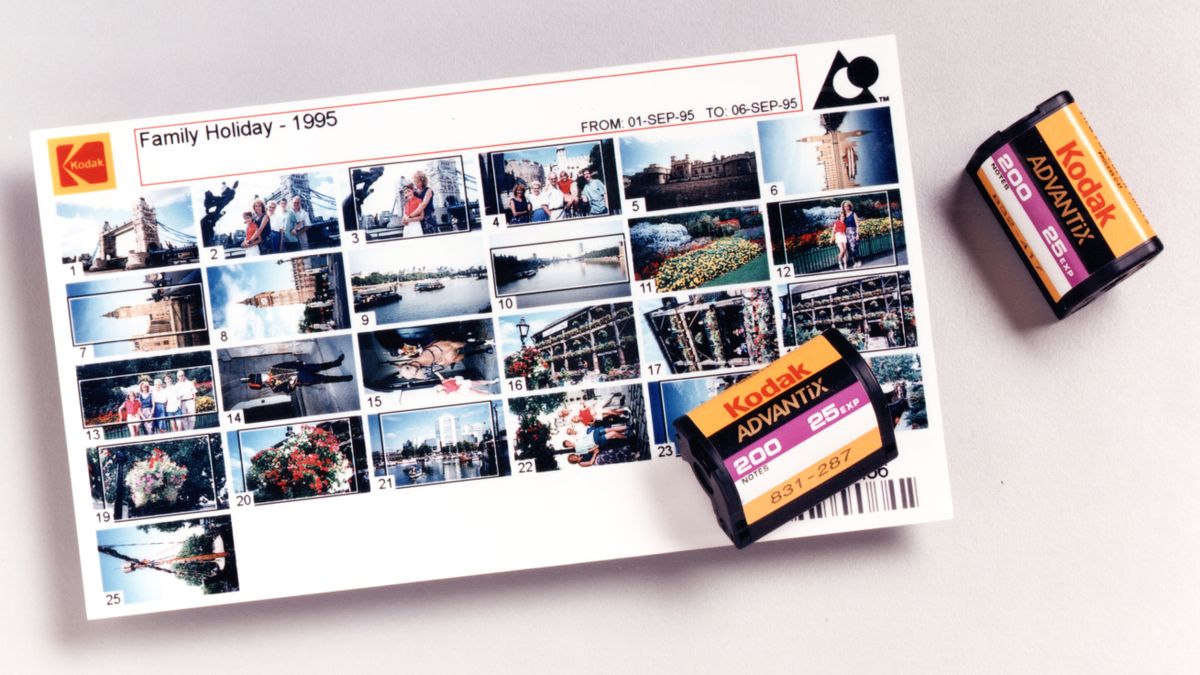

The Advanced Photo System was designed to eliminate all film handling issues because users never actually saw the film at any point… even the processed film was returned in the APS cartridge. The higher-end APS cameras even allowed for the cartridge to be removed mid-roll and reloaded later to resume shooting from the next unexposed frame. A set of four markers on one end of the cartridge indicated the status of the film inside – unexposed, partially exposed, exposed but not processed and, finally, processed. The APS cartridge was drop-loaded – it could only fit into the camera one way – and the film prewound. It was available in 15-, 24- and 40-exposure lengths.

APS used 24mm wide film with just two perforations at the base of the frame, and a transparent magnetic coating that allowed different format frames to be obtained from the same roll – these were called Classic (which has given rise to the naming of the ‘APS-C’ sensor size), Panoramic and High Definition. All images were recorded as HD frames – at 30.2x16.7 mm, representing a 1.25x crop on 35mm – and then cropped to 25.1x16.7 mm (1.44x) for the C format print and to 30.2x9.5 mm (1.36x) for the 16:9 aspect P format. Consequently, if you re-ordered a print, you could have it in any format regardless of what was originally set in the camera. The magnetic coating – called the ‘information exchange’ system or ‘ix’ for short – also allowed for additional data to be recorded along with the image, including the date and time, exposure details, and a short caption. The low-end APS cameras had an optical information exchange arrangement that only recorded the selected aspect ratio for the print. APS film was given the format designation ‘IX240’ and also known as 24mm. The higher-end cameras used an LED-based optical system to drive the film transport rather than conventional sprockets.

As the processed negatives were returned to you in the original cartridge, it was accompanied by an index print of thumbnails and everything – including each print – was linked via a six-digit ID code in a XXX-XXX format. Of course, the index print was unnecessary with slide film which was returned mounted in the same size frames as 35mm to maintain compatibility with the existing projector tray systems.

For the record, although today’s APS-C sensor size is directly named after the Classic APS film format, at 23.6x15.7 mm, it’s slightly smaller and hence the crop factor of 1.5x. With its first four generations of the EOS-1D series pro DSLRs, Canon used APS-H size sensors with an imaging area of 27.9x18.6 mm, which is close to the APS High Definition format and gave a crop factor of 1.3x.

Starting line-ups

The early emphasis with APS was on compact and fixed-lens zoom cameras, and the five main protagonists all initially launched full line-ups of models from entry-level to high-end, the latter utilizing all available convenience features. Later on, there were disposable APS cameras too, but with very few of the system’s key features.

As with the cropped sensor sizes today, a number of camera makers could see the potential in size and weight reductions that would be achievable with an APS SLR system, and this resulted in the Nikon Pronea, Minolta Vectis S and Canon EOS ix models.

The downside of APS for enthusiast-level shooters was mainly being limited to using color negative film, as slide films from both Kodak and Fujifilm – available only in ISO 100 speed – weren’t around for very long and, what’s more, were never available in some markets including the USA. Additionally, ISO 800 speed color neg film didn’t arrive until 2000. Kodak also made a chromogenic B&W film (i.e. for processing in C-41 color neg chemistry) in the APS format. It was rated at ISO 400 but, being chromogenic, it had the latitude to range up to ISO 3200. There were no traditional B&W stocks in APS and, even if there had been, the film’s narrower width and the cartridge design would have likely been deterrents for the home darkroom practitioner.

Minolta, in particular, put quite a bit of effort into its Vectis S APS SLR system, taking the opportunity to redesign the camera bodies to take better advantage of the size reductions and using a new, smaller diameter lens mount. There ended up being eight V-mount lenses – including a 400mm f/8.0 mirror telephoto – and, interestingly, Minolta also used the S-1 body and the V mount as the platform for its first DSLR (the DiMAGE RD3000).

Canon also took the opportunity to be more adventurous with the design of the EOS ix, but it retained the EF mount, so the 1.25x crop factor applied. This perhaps suggests that Canon didn’t have a lot of faith in APS for serious shooters but, as it happens, the company did produce the bestselling APS compact. It’s been estimated that Canon sold more of its ultra-compact ELPH (named IXUS in some markets) than all other APS compacts combined, and it certainly made the most of what could be achieved with the smaller film format. A smart stainless-steel body added to the appeal.

The odds against

Despite the clever work done with the system SLRs (and the higher end compacts), APS was inevitably perceived by the market a snapshot format. This was just one of the many odds stacking up against it in the late 1990s and into the start of the 21st century. The others were the ongoing 35mm minilabs couldn’t be adapted, which took APS out of the equation for outlets like pharmacies. To get to the required volumes, APS processing became more centralized, thereby increasing both the turnaround times and the cost to consumers. In comparison, you could have your 35mm film processed and printed while you did the rest of the shopping. Plus, with 35mm compacts becoming much smaller and digital compacts offering far more convenience – albeit still at a bit of a premium in terms of price – APS ended up being squeezed by both the past and future imaging technologies. The news pages of Australian Camera magazine at this time reported on as many new digital cameras – and remember that compacts led the charge into the consumer market – as the APS arrivals. By 2000 the former were outnumbering the latter.

If APS had arrived 10 years earlier, it would have been a very different story, but history and technology conspired against a system that really did have some merits if the photo world had still only been analog. It’s probable that Kodak – and more than likely the Japanese too – knew it was likely doomed from the start but, by that stage, so much had been spent on R&D, taking it to market was the only way to possibly recoup some costs. The same thing happened in the audio industry with Philips and the Digital Compact Cassette (DCC), which was an even shorter-lived format than APS.

The APS SLR sales started to decline quite dramatically from around 2000 onward and, by January 2002, we were listing only three models in Australian Camera Magazine's Buyer’s Checklist. By the May 2002 issue, these had gone too and, in September 2003, we replaced the APS camera listing entirely with one for DSLRs.

Digital distractions

I well remember the hoopla surrounding the launch of APS and then, certainly in Australia at least, Kodak almost immediately seemed to lose interest in it. There were, of course, plenty of subsequent introductions of new Advantix (Kodak’s branding for APS) cameras and films, but it was also busy building its Digital Science range of digital cameras which were steadily becoming more capable in terms of both features and image quality (it even regained interest in 35mm).

By the start of 2000 there had already been 16 Kodak digital models, which puts paid to the assertion that Kodak wasn’t on the ball with digital imaging, but it also highlights the dilemma that faced most of the major photo companies at this time. All were reluctant to give up film when it still wasn’t really obvious what might happen with digital imaging. Yes, it was here to stay, but how big was it going to be? This manifested itself in a number of hybrid products like Kodak’s Advantix Preview – announced at Photokina 2000 – which was an APS film camera with an LCD display like that of a digital camera.

There was a CMOS sensor set into the viewfinder that captured the image digitally while it was simultaneously being recorded to film. However, there was only sufficient memory to recall the last image taken, so the ‘preview’ aspect was only for the print – enabling you to decide the format and whether you wanted more than one copy of a shot (or, indeed, none) – and not for the exposure itself. Kodak’s thinking was that the preview facility was a digital-like convenience combined with the superior image quality of film (as even the smaller-than-35mm APS format still delivered back then).

With so much working against it, it’s surprising that APS lasted as long as it did, although it only really flourished for the first few years following its launch. As digital cameras began to challenge even the popularity of 35mm, industry support for APS quickly waned and, over a relatively short period of time, the camera makers began to end production – Kodak itself in 2004 (although it also ended its involvement in 35mm cameras in most markets at the same time). Film production continued until 2011 when both Kodak and Fujifilm finally called it a day. Agfa’s Futura range had finished in 2004 after the its imaging business became the standalone AgfaPhoto, and Konica ended Centuria APS film in 2006 (a branding it also used on 35mm color neg films).

A surprising amount of expired APS film has remained available over the last decade or so, but supplies are starting to dwindle now and will continue to do so as there is no current manufacturing, nor any plans to restart it (such as had happed with 110). Perhaps more restrictively, the processing options are very limited. Preloved cameras are plentiful and destined to become even cheaper as the film supply dries up. As there’s no easy hack of an APS cartridge to reload it with something else, all APS cameras are heading towards mere curiosity value.

Consequently, if you want to tick off using an APS camera from your list of photography experiences, you’d better hurry. But is it worth the effort? Frankly, no… even though APS spawned some really interesting camera designs with Canon’s ELPH leading the pack, the Nikon Nuvis S, Fujifilm Fotonex 1000ix, Minolta Vectis Weathermatic Zoom and the Yashica Samurai 4000ix are all worthy of a mention.

The Advanced Photo System had the potential to take film photography further had film itself still had plenty of life in it. The early sales were encouraging and, if they had continued to grow at the same rate, there would have undoubtedly been many more higher-end cameras and a greater variety of film types. In some ways APS would have enabled a smoother transition into digital imaging and this could be seen in products such as the film scanners introduced for the format by Fujifilm, Konica and Olympus. The ix system allowed for much greater automation of processes such as film scanning. The Fujifilm system also included a photo player, so APS images could be viewed on a television. However, as it happened, after a slow start, digital imaging arrived in a great rush and, while the image quality took a while to catch up, the numerous conveniences easily sealed the deal for photographers.

Read more

Best film cameras today

The best film to buy

The rise and fall of the 35mm compact camera

The rise and fall of 110 film cameras

Best darkroom equipment available today

The best film scanners

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.