Ricoh GXR – the whacky mirrorless camera with its interchangeble sensor/lens modules

Is it worth buying an older, used digital camera? It’s a question I get asked a lot and I've always erred on the side of ‘no’, but there are exceptions and Ricoh’s unusual take on a mirrorless system from 2009 can still work today.

The Ricoh GXR was an innovative camera dating back to 2009. Back at the time the first mirrorless camera were coming onto the market, Ricoh took a radically different approach to making an interchangeble lens camera that was smaller than a DSLR. It's whacky idea was a camera where you changed both the lens and the sensor at the same time - using a series of modules.

I have been seeing how the GXR stack up in 2025 - but before I get to that, here is the history…

The history

It’s the middle of 2009 and the photography world is starting to get to grips with a whole new breed of camera. First Panasonic at the previous year’s Photokina and then Olympus repackaged the Four Thirds format sensor – now renamed Micro Four Thirds – into interchangeable lens cameras which did away with the traditional SLR mirror box and optical viewfinder.

Panasonic opted for having an integrated electronic viewfinder in its Lumix G1 giving a design reminiscent of a very compact DSLR while the Olympus PEN E-P1 adopted a styling very similar to that of its Pen F half frame 35mm, but which didn’t have an eyelevel viewfinder at all.

Both these cameras were significantly smaller and lighter than even the most compact DSLR which was achieved partially by using the MFT sensor and also by eliminating the bulky reflex assembly at the heart of both film and digital SLRs. While the term ‘mirrorless’ is universally used now, early on, a widely-used classification was ‘Compact System Camera’ (CSC) which neatly summed up what they were… compact camera bodies in a system of lenses and accessories.

Nobody knew where CSCs were heading except that ‘compact’ was the big selling point for both the bodies and the lenses. Enthusiasts didn’t really take them all that seriously and the early marketing was certainly aimed at the users of fixed-lens compacts who wanted to upgrade to something with more versatility.

In January 2010, Samsung stepped up a sensor size with its ‘APS-C’ format NX-10 which was still very compact compared to any DSLR using this sensor size, but there was still a belief that smaller was better so Pentax introduced the Q line in June 2011 and the 1 Nikon system appeared just a couple of months later.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The tiny Q series cameras were initially built around a 6.77x4.55 mm BSI CMOS that was very compact indeed. The former, called the S10, had a BSI-type CMOS mated with a zoom equivalent to 24-72mm f/2.5-4.4 which was also exceptionally compact. In both cases, the ‘10’ referred to the effective resolution in megapixels. There were two A12 modules – so, ‘APS-C’ sensors with an effective resolution of 12.3 megapixels – with prime lenses; namely (effectively) a 50mm f/2.3 and a 28mm f/2.5. The M mount unit used a similar sensor with the same resolution and then, finally, there was the A16 module which combined a 16.2 megapixels ‘APS-C’ sensor with a 24-85mm f/3.5-5.5 zoom, and was the biggest and bulkiest of them all.

It was possibly the A16’s size that suggested what had looked like a clever idea at the time of its launch maybe couldn’t be developed very much further. There was also a bit of an identity crisis – was it really only a compact camera with some added versatility or something more serious? And the pixel war was raging which raised the issue of how upgrades might be handled… you’d have to buy a new lens as well as the higher-res sensor and faster processor. It would have been easy to update the body with, for example, an adjustable monitor screen, but down the track, it started to become obvious that the module concept would be problematic, particularly in terms of implementing new technologies. In a way then, its advantages were also its disadvantages. Perhaps after the megapixel race calmed down and the resolution of ‘APS-C’ sensors settled at where it is now – in the region of 20 to 26 MP – there might not have been so much of an imperative to upgrade the modules, but as we’re now seeing, it’s more about more powerful processors which can perform complex functions such as AI-based subject recognition.

The Ricoh GXR system was launched at the end of 2009 and the last new module, the A16, in February 2012 by which time Panasonic, Sony, Samsung and Olympus were building mirrorless camera systems with bigger choices of lenses and bodies with more features and better capabilities.

Furthermore, the competition was hotting up with the arrival in early 2012 of Fujifilm’s X mount system – introduced with the X-Pro1 – and then, mid-year, Canon’s EOS M system, both using ‘APS-C’ size sensors.

Slowly but surely the formula for mirrorless cameras was taking shape and it was evolving to use only the ‘mainstream’ sensor sizes – the first full frame bodies were not far away – and a conventional lens mount. More significantly, what had initially been considered an ILC category supplementary to DSLRs was emerging as their replacement… and the Ricoh GXR was never going to stack up here.

Ricoh’s original road map had plans for up to 20 lens modules and there was talk of full-frame units down the track, but in the end there were just five plus the M mount model. There were also ideas for other components that could use the 68-pin connection, including a projector, a large capacity data storage unit and a mini photo printer that would have turned the GXR into an instant camera, but none of these went into production. After no new product activity for over three years, the system was finally announced as discontinued in late 2015.

The Ricoh GRX today

However, none of this history prevents the Ricoh GXR being a really interesting proposition today, not just because the concept still has merit, but because it actually works well as a compact interchangeable lens camera system. If you accept that ‘it is was it is’, the GXR has plenty going for it and it’s a lot of fun to use.

| Name | Lens | EFL | Sensor type/resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| A12/50 | 33mm f/2.5 Macro | 50mm | CMOS, 15.7x23.6 mm, 12.3 megapixels |

| S10 | 5.1-15.3mm f/2.5-4.4 | 24-72mm | CCD, 5.7x7.6 mm, 10.0 megapixels |

| A16 | 15.7-55.5mm f/3.5-5.5 | 24-85mm | CMOS, 15.7x23.6 mm, 16.2 megapixels |

| P10 | 4.9-52.5mm | 28-300mm | BSI CMOS, 7.59 mm, 10.34 megapixels |

| A12/28 | 18.3mm f/2.5 | 28mm | CMOS, 15.7x23.6 mm, 12.3 megapixe |

The A16 module obviously delivers the most resolution compared to contemporary ‘APS-C’ mirrorless cameras and its 24-85mm zoom performs well. However, 12.3 megapixels is still a reasonably useful amount of resolution for many applications and both the prime lenses are very good indeed with the 50mm also labelled ‘macro’ as it focuses down to seven centimetres which gives a maximum magnification ratio of half life size. With RAW capture – which uses the Adobe DNG format – the A12 modules deliver a file size of around 20 MB (depending on the subject content, of course) and a maximum JPEG quality of close to 5.0 MB. The A16 unit – which uses a Sony-made sensor – generates average file sizes of 24 MB and 6.0 MB respectively.

Arguably, the most interesting of the GXR modules is the Mount A12 unit which, as noted earlier, combines the Leica M mount with a modified version of the 12.3 MP ‘APS-C’ sensor which doesn’t have an optical low-pass (or anti-aliasing) filter. Additionally, it has both a focal plane shutter with a top speed of /4000 second and a sensor-based shutter that runs up to 1/8000 second. Of course, there’s a focal length magnification factor of 1.5x – as there was with the Leica’s M8 – but otherwise, this module turned the GXR into a very neat little digital M mount camera… not to mention a comparatively affordable one too.

Better still, the GXR body can be fitted with a plug-in EVF – the compact VF-2 – which is tilt-adjustable and has a resolution of 920,000 dots (same as the monitor screen), but obviously looks a lot sharper because of the much smaller screen. The VF-2 is handy with any of the lens modules, but makes an M mount GXR into a great little package… and the system is young enough to have a focus peaking display to assist with manual focusing. It’s only in white and at a single intensity, but it’s still more useful than the classic rangefinder in terms of showing exactly what’s sharp and what isn’t. There’s a second option which renders the live view the image as a B&W negative so it’s easier to see the peaking display – but obviously it needs to be switched on and off – so the color mode is more convenient. Alternatively, there’s a magnified image display with settings of 2x, 4x or 8x.

Not surprisingly, the M mount module was a big hit and possibly helped sell more GXR body units than any of the others. Indeed, initially Ricoh had plans for more of what it called ‘extension units’ with mounts primarily for fitting legacy lenses. These lens mount modules could have been a way to keep the system going, perhaps with the updated body suggested earlier. A K mount option would have made a lot of sense, but Ricoh had purchased Pentax in July 2011 and the Pentax K-01 – a K mount mirrorless camera – was launched in February 2012 so avoiding competitive products may have stymied that idea. Also, licensing would likely have been an issue, although it wouldn’t be too long before Sony was handing out E/FE mount invitations to all and sundry, and the MFT group would likely have welcomed a new member of Ricoh’s caliber.

Features

Despite the earliest components of the system now being over 15 years old, the Ricoh GXR doesn’t lag so very far behind compared to today’s compact mirrorless cameras as far as still photography is concerned.

Video, of course, is another story and this is where a lot of the recent progress has been made, but it was a feature yet to gain any traction at the end of the ‘noughties’. The best you can get is HD res (i.e. 720p and not Full HD) at either 24 or 30 fps in either MPEG-4 or AVI Motion JPEG depending on the lens module, and only with mono sound via the built-in mic. There’s no manual controls – except, of course, for focusing when you’re using the M mount module – and no connection for an external microphone so, even when it was new, video wasn’t the GXR’s strong point.

For photography, the period features are contrast-detection AF with nine measuring points, continuous shooting speeds of between 2.5 and 5.0 fps depending on the module, and a less-than-logical menu layout. However, the AF is still reasonably brisk and there’s a handy ‘Snap Focus’ mode which can be preset to one of eight distance settings from one metre to infinity which are automatically set – virtually instantaneously – when the shutter is button is depressed (and with half-press or full-press options). This feature continues in the current Ricoh GR IIIx fixed-lens compacts as does the multi-point white balance measurement which was actually first introduced in the CX series compacts. This takes multiple measurements across the frame and the colour balance is then adjusted area by area rather than by applying an average setting. This takes into account that different parts of a scene are often differently illuminated or have different colour balances (i.e. broad sunlight and shadow).

There’s auto bracketing for white balance as well as exposure, ISO and for colour whereby three frames are recorded, one in the preselected colour, one in B&W and one with a preset monochrome tint. The color setting options are Vivid, Standard and Natural, but you can create two of your own, while the toning/tint effects for B&W are sepia, red, green, blue and purple. The Scene modes include the staples for portraiture, landscapes, close-ups, sports action and night photography while, later, special effects were added via a firmware upgrade and these included Soft Focus, Cross Process, Toy Camera, Miniaturise and High Contrast B&W.

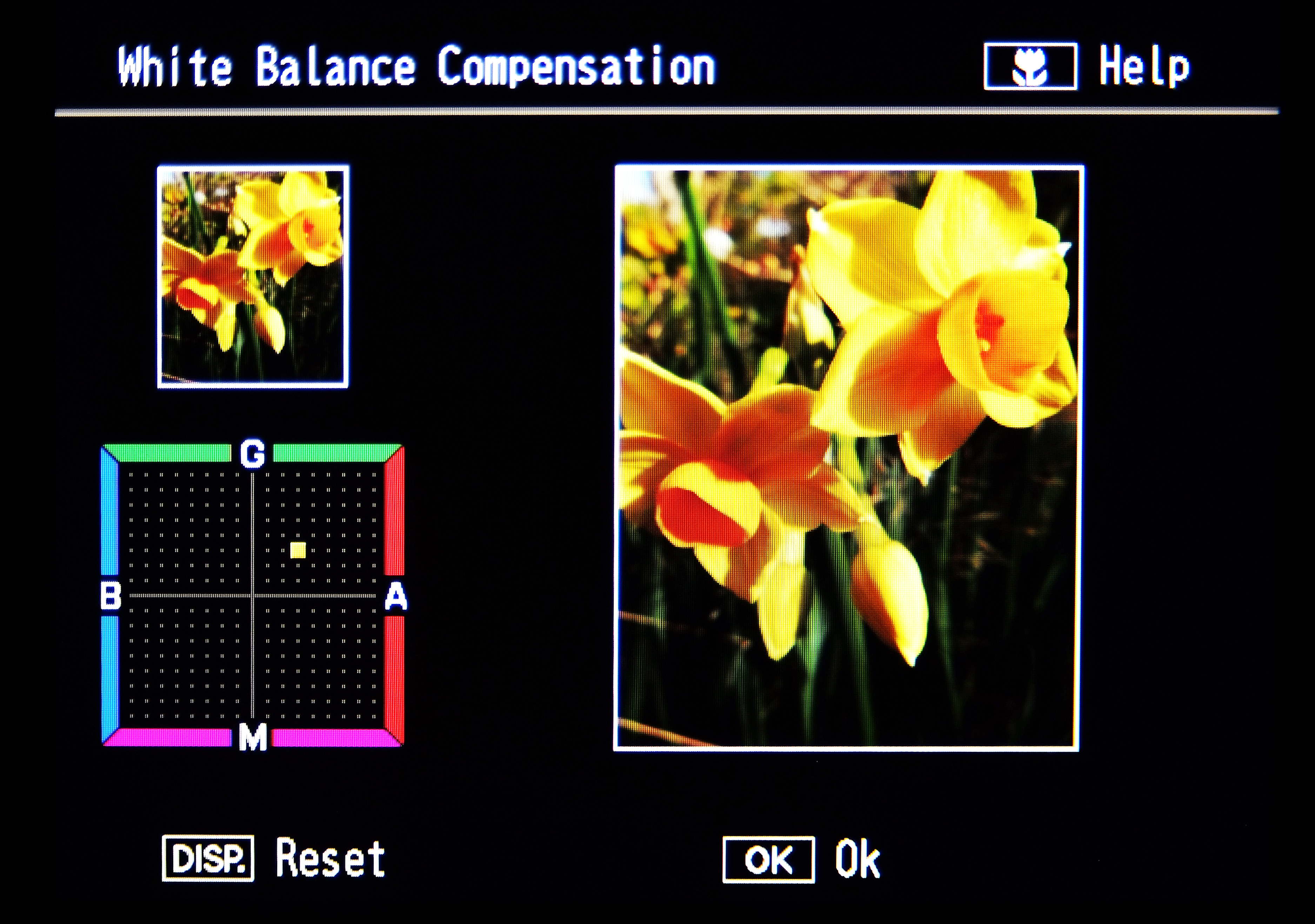

By today’s standards the GXR is still pretty well featured including with all the manual controls and overrides you’d expect on a new mirrorless camera. There’s noise reduction, high ISO noise reduction (adjustable for threshold from ISO 200 to 3200), dynamic range expansion, white balance correction (set via a colour square), distortion correction and auto aperture or shutter speed shifting (depending on the exposure mode). Post capture, you can edit in-camera with Auto/Manual Levels Corrections (which works the same way it does in Photoshop), White Balance Compensation and Skew Correction. There’s also an intervalometer (set for up to 99 frames or unlimited), a programmable self-timer and copyright info input.

Handling

Even with the bulkiest A16 module fitted, the GXR is still a very compact camera. The main body dimensions aren’t far off those of the GR III models, but obviously the lens units add extra depth… although not very much in the case of the S10 and P10. Add-on EVFs always look a bit clumsy, but it’s definitely worth having so worth tracking down if you’re looking at a preloved body without one.

At the time of the system’s launch, Ricoh emphasized the reliability and durability of the 68-pin interface and the guide rail arrangement that ensures a reliable coupling between the GXR body and the lens units. It’s not entirely goof-proof because you can misalign the two components and they’ll still lock into place, but it should be very obvious visually and, in case you still miss it, the camera refuses to play ball until you do something about it.

The coupling is undoubtedly massively over-engineered so it’s hard to see even a well-used system having any issues, but the design did prevent weather-proofing and make sure you get the clip-on rubber dust covers for both the modules and the body units… these are as important as lens and body caps.

The external control layout is conventional with a main mode dial, a front input wheel and a rear ‘ADJ’ adjustment lever, a four-way keypad on the back panel and a small scattering of function buttons. There are two dedicated multi-function controls – the left/right pad actions – which can be assigned from a load of stuff plus four ‘ADJ’ lever settings for various capture-related settings including ISO, white balance, exposure compensation, the auto bracketing mode and much more. You can then cycle through what’s been assigned so you can set it up to enable quick on-the-fly adjustments of those key exposure and white balance settings. Not as quick as if you had touch screen controls, but still pretty efficient.

The monitor screen itself is showing its age with its now comparatively low resolution and fixed position, but it works well enough. More of a challenge is the tiny typeface that Ricoh used in the menus and displays with both the GXR and the CX-series compacts.

The menu layout comprises just three tabs so you’ll spend a lot of a time searching for things until you become familiar with where they are, but you can create up to three sets of ‘My Settings’ which are then selectable via the main menu dial. The customisable ‘ADJ’ level mentioned earlier also cuts down the number of times you’ll need to trawl the menus when shooting. However, the undoubted convenience of

‘My Menu’ pages was still before the GXR’s time. However, the displays still include all the essentials – a dual-axis level display, a real-time histogram, a highlight warning and a choice of guide grids.

In practice then, the user experience isn’t so very much different from a current mirrorless camera, but minus the efficiencies of a touch screen monitor and a better-organised menu system. Basic set-up and operation will be familiar no matter what else you’ve been shooting with.

Performance

Speed-wise, the Ricoh GXR is very much of its day and, of course, we’ve been treated to some significant advances in both AF performance and continuous shooting frame rates over recent years. It’s not quick, but if you’re thinking street photography or something very compact, but capable to travel with then it’s fast enough. Of course, f you’re using the M mount module then the AF speed isn’t an issue. In terms of exposure control and white balance, the GXR is still more of a modern than a classic.

The R/GR series of 35mm subcompacts built a cult status on their combinationof portability and performance with a big part of the latter being the lenses. These were so good that, in fact, a small batch of 21mm f/3.5 ultra-wide from the 35mm GR21 (2001) was offered as a manual-focus version with a Leica L39 screw mount. The dedication to high-quality optics continued with the GR lenses for the GXR which, apart from being each optically matched to the sensor, are very highly corrected to give excellent uniformity of sharpness and brightness. There is undoubtedly some digital correction going on too, again specific to the lens and sensor combo. Consequently, the A12 primes, in particular, are exceptionally strong performers optically and well corrected for both distortion and chromatic aberrations.

The 24-85mm is the pick of the zooms and is again very well corrected. It’s versatile too, and the 16.2 megapixels sensor delivers plenty of well-defined detailing along with smooth tonal gradations. Of course, noise reduction processing for JPEGs is something else that’s progressed in leaps and bounds since the GXR system components were new, so none of the sensors have sensitivity ranges that extend beyond ISO 3200, and only the A16 is capable of anything like the high ISO performance that we’d expect today. Best-quality JPEGs look fine up to ISO 800 and still pretty good at ISO 1600 which is also true of the A12 sensors, but even ISO 800 is pushing things with the S10 and P10 units with their tiny imagers… although the latter’s 28-300mm equivalent zoom is brilliantly packaged and hugely versatile.

Verdict

If there had been a GXR II body with a higher res, tilt-adjustable monitor and at least a couple of 24 MP ‘APS-C’ lens modules, Ricoh’s concept would still arguably be in the mix as a compact mirrorless camera system. The biggest impediment to long-term progress was forcing users to buy a new lens with a new sensor, and while a bunch of mount units – let’s say, K, E and M43, along with M – might have worked, what looked like a bright idea at the start quickly lost its appeal after you bought into it… if only because the conventional systems from the likes

of Canon, Panasonic, Samsung, Olympus and Sony were soon all offering more for less. However, it’s that original appeal that makes the GXR worth looking at today because the concept did work and, now you know the history and so don’t have any great expectations for anything more, it still works.

With the 28mm and 50mm modules, the overall package is very compact, but with great quality optics and enough resolution for plenty of applications especially, as it now happens, anything you might want to do online such as social media. The M mount module is also worth considering and, of course, you can fit other classic MF lens via an adapter. This unit turns the GXR into a nifty little digital RF camera that’s actually a whole lot of fun to use, especially with the VF-2 EVF.

The A16’s extra resolution brings the GXR even closer to current image performance levels and, while it lacks any of the camera tech that’s appeared over the last date, it still has all the basics and quite a few frills too. Importantly, there’s all the manual controls and overrides for the experienced shooter to effectively deal with focus, exposure and white balance, plus enough for a bit of creative dabbling such as picture controls – the B&W mode is noticeably filmic in its look – and special effects, especially if all the firmware upgrades have been done (and there were quite a few of them along the way).

On one hand, it’s easy to see why, at the time, Ricoh thought that the GXR was a good idea, and it’s equally easy to see why it would have been apparent from quite early on that it really wasn’t. But it hasn’t been a total failure because, while it may be even more of a curiosity today, it’s also still surprisingly workable and, better still, a great deal of fun to use.

There are a few other unusual choices if you want to relive the early days of mirrorless cameras, including the Pentax Q and Nikon 1 miniature systems, but nothing is quite as unique as the Ricoh GXR.

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.