Scientists build a "honeypot" system of fake cameras and networks to fool hackers trying to steal US military secrets

"I will create realistic fake videos, in order to deceive an attacker into believing that they have co-opted a camera system"

As technology evolves, our control over it diminishes, and opportunities to manipulate it for iniquitous purposes become available. Espionage and sabotage no longer require James Bond to cable drop into a room, as individuals can now remotely hack WiFi systems, and access cameras and sensitive information from the comfort of their own homes.

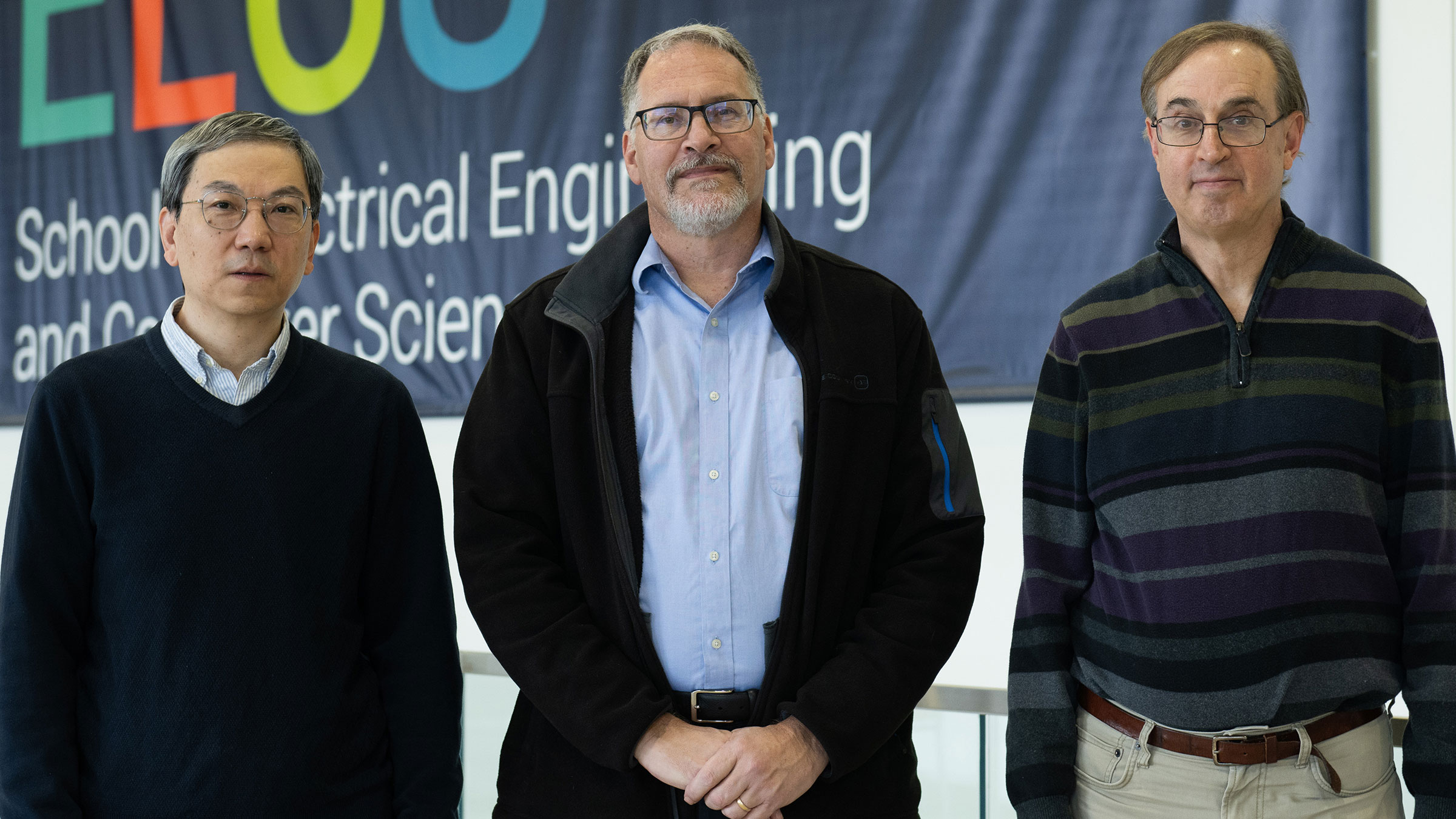

This threat is a serious concern within the military. So much so that three computer science researchers in the Penn State School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) are creating their own special ops team to build a “honey pot” tech trap.

In other words, a decoy suite of fake networks, devices and domains to entrap and deceive the hackers.

The team was granted a 24-month grant of $557,000 (around £450,000, AU$885,000) from the US Army’s Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM), with the possibility of renewal, to fund the project of deception.

Once the honeypot scheme reveals what the adversary's intentions are, the appropriate agencies can take further action, and the team plan on working with DEVCOM to hone the process as needed.

“We are seeing that hackers are getting very sophisticated, and they’re trying to compromise assets from multiple domains, such as air and land, to learn intelligence from both systems,” said co-principal investigator Tom La Porta, Evan Pugh Professor and director of EECS.

“They can compromise a Wi-Fi network, for example, and see there’s a ship on the network. From there, they can hack into the ship’s GPS. So, that would be multidomain deception: going from cyber to sea.”

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The other two members of the dream team trio are Guohong Cao, a distinguished professor of computer science and engineering, and David Miller, professor of electrical engineering. They plan to work on building sophisticated, multidomain fake networks that dangle a carrot in front of attackers, who then unknowingly upload their malware – so researchers can gather information about their adversaries and their tactics.

La Porta is in charge of developing the fake networks, Cao will build them, and Miller will develop and enhance the fake video feeds deployed on the honeypot through real-time video editing.

La Porta emphasized the importance of consistency across their honeypot domains, meaning that all the ‘hackable’ systems – WiFi routers, fake cameras, and smart system devices like light switches and thermostats – must be cohesive to fool the tech-savvy hackers. This is because hackers will typically verify that a system is legitimate by testing a light switch or thermostat and seeing if the camera of the same network registers the change.

“If the hackers think they have a camera and a light switch in the same room, from a network perspective, the addresses of these devices have to look like they’d be on the same network,” La Porta said. “To keep track of all the fake devices and networks, we are building a database that has the attributes of every fake device and what its impact on its environment is.”

Cao added: “We will build honeypots using software to emulate various devices that appear real but are actually just software. These honeypots will be deployed on a cloud-based system like Amazon cloud computing, where anyone, including hackers, can see and interact with our fake cameras, router, Google voice, network devices and more.”

Going into the way video is used, Miller explained: “Using generative deep neural network learning, I will create realistic fake videos, in order to deceive an attacker into believing that they have co-opted a camera system.

“This may involve generating fake video from scratch, consistent with the supposed physical location of the network that has been infiltrated, or editing an existing video to make it consistent with underlying weather conditions, such as displaying rain or snow, or the time of day, such as moving shadows throughout the day.”

If attackers believe the systems are legitimate, they will spend time observing the fake systems, wasting time they could be spending on real systems, La Porta added. And once hackers upload their malware, researchers can get an idea of their intentions.

“By interacting with our honeypot, they tell us what they want and how they will do their attack,” Cao said. “Do they want to hack the GPS of a submarine, observe troop movements, understand the layout of a military base, upload ransomware to ask for ransom, mine bitcoin or something else?”

You might also like…

Feel like conducting your own secret operation? Why not take a look at our guides to the best fake security cameras, the best camera drones, and the best spy cameras.

After graduating from Cardiff University with an Master's Degree in Journalism, Media and Communications Leonie developed a love of photography after taking a year out to travel around the world.

While visiting countries such as Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Bangladesh and Ukraine with her trusty Nikon, Leonie learned how to capture the beauty of these inspiring places, and her photography has accompanied her various freelance travel features.

As well as travel photography Leonie also has a passion for wildlife photography both in the UK and abroad.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.