Astrophotography in November 2023: what to shoot in the night sky this month

Everything you need to know about what’s happening in the night skies above this month

November is a fine month for astrophotography, with long nights leading up to next month’s solstice. It’s getting colder down here, but crisper above, with the bright winter stars of Taurus and Orion rising high into the sky at night.

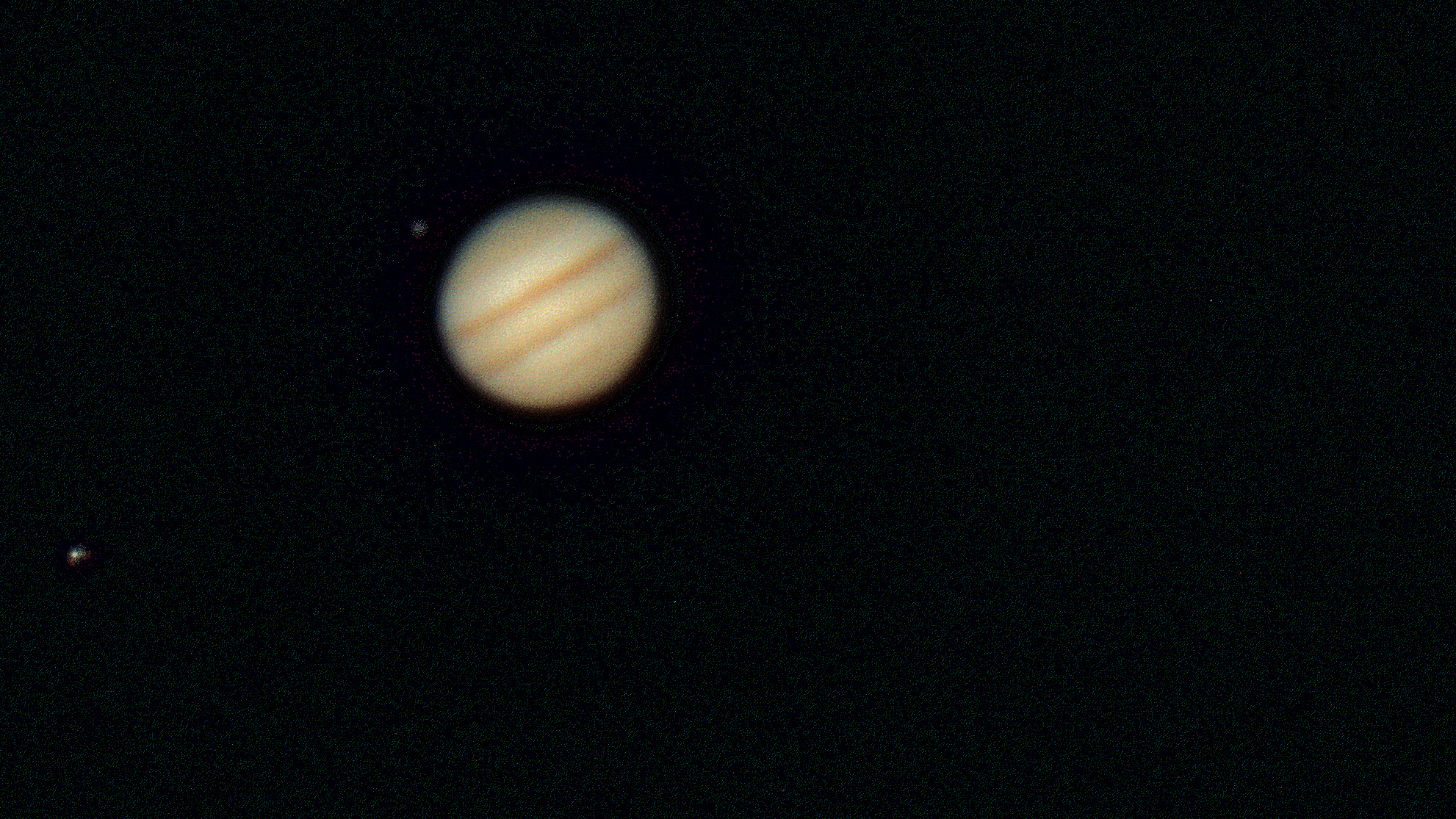

This month is the best in 2023 to image Jupiter, which can be both hugely challenging and rewarding. Add a few conjunctions, a trio of meteor showers and the rise of the full ‘Beaver Moon’ and November 2023 promises to be a great month for capturing the sky night.

Read: Night photography techniques, tips and tricks

Thursday, November 2: Jupiter at opposition

Since Earth orbits the sun faster than the far-outer planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – once every year it gets between them and the sun. This month it’s the turn of Jupiter, which will today be at its closest to Earth in 2023 at a mere 370 million miles. This means a spike in its brightness, but also its visibility, with the giant planet ‘up’ all night and 100% lit by the sun – a bit like a full moon. Any kind of image of Jupiter will show some of its big Galilean moons – Ganymede, Callisto, Europa and Io.

Read: Best CCD cameras for astrophotography

Sunday, November 5: Monthly dark sky window opens

Sunday, November 5: Monthly dark sky window opens

Astrophotography is best attempted when the moon is down. Tonight sees our natural satellite reach Last Quarter, which sees it rise after midnight. That begins 12 nights of moonless darkness until the waxing crescent moon begins to get bright around November 17.

November 4-5 and 11-12: Southern and Northern Taurid meteor shower peaks

With their peaks on successive weekends, the Southern and Northern Taurids are both minor meteor showers. Although the peak for each can be drawn out, the source constellation, Taurus, is above the eastern horizon around midnight. On November 5, a 25%-lit crescent moon will rise a couple of hours later while on November 12 a barely-lit crescent moon will be visible in the minutes before sunrise. At around five ‘shooting stars’ per hour neither peak is much to get excited about, you might think, but both the Southern and Northern Taurids are known for producing bright fireballs throughout November.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Read: How to photograph a meteor shower

November 9: Conjunction of the moon and Venus

From about two hours before sunrise, there’s a chance to catch a close conjunction of a 14%-lit crescent moon in a ‘smiley face’ orientation extremely close to the bright planet Venus. This is arguably the shot of the month to attempt, which you can do by using a 200-400mm lens and experimenting, starting from ISO 100-400, f/6.5 and f/9 and 1/125 to 1/500 seconds.

Read: The best cameras for astrophotography

November 15/16/17: A beautiful crescent moon

For most of 2023, there’s been a bevy of planets passed by a delicate crescent moon emerging into the post-sunset sky. Not so this month, but the crescent moon remains a wonderful target for astrophotographers. Be outside looking west after sunset on these three nights and you’ll have a chance of capturing the slim lunar crescent slightly brighter (7% lit on November 15, then 14% and 23%) and higher in the sky on each successive evening. Look out for delicate ‘Earthshine’ on the moon’s darkened limb.

Read: When to photograph the moon

November 17-18: Leonid meteor shower

The meteor shower to plan for in November is the Leonids, which produce around 15 ‘shooting stars’ per hour, but it’s regular, with 100-per-hour displays possible. This year the peak occurs in dark moonless skies so it’s worth putting a camera outside pointing roughly east to see if it picks up any of the Leonids characteristically bright meteors, which often have long trails.

Read: Best star tracker camera mounts

November 19 and 20: Moon and Saturn

On November 20 a 56% lit waxing gibbous moon will be a mere 2.7° from Saturn high in the southeast. That’s the shot to get, but as is so often the case with mon photography you can practise the night before. On November 19 the moon will be 44% lit and approaching the planet, though slightly farther away.

Read: Best equatorial mounts

Monday, November 27: ‘Beaver Moon’ rises

Find out when moonrise is where you are tonight and be in a location looking east at that time. Within minutes you’ll see the orange full moon rise during dusk – a stunning sight if you have a low horizon.

Read: How to photograph the full moon

Deep sky shot of the month: a ‘full’ Jupiter at its best

With Jupiter and Earth the closest to each other they get in 2023, early this month is a great time to image the giant planet. Visible all night – rising in the east and setting in the west – it will also be the brightest it gets. The simplest way to photograph it is to capture its brightness in a landscape by using any wide-angle lens (55mm or below). A particularly good way of doing this is to spend an hour or so with it just after sunset while at a southeast-facing location on the coast or lake. You can then capture ‘Jupiter-light’ reflecting off the water as it rises into an ever-darkening sky.

For true planetary astrophotography, things are much more complicated. You’ll need a telescope with a high frame rate planetary camera (such as a CCD camera for astrophotography) attached, plus a laptop. Wait until it’s way above the horizon and then shoot video, later stacking the best frames to create a less noisy image that may – if you’re lucky – show the planet’s cloud band and Great Red Spot. There’s a useful introduction to this technique on AstroBackyard.

Read: Best deep-space telescopes

Read more:

Astrophotography: How-to guides, tips and videos

Astrophotography tools: the best camera, lenses and gear

The best star tracker camera mounts

The best light pollution filters

Jamie has been writing about photography, astronomy, astro-tourism and astrophotography for over 15 years, producing content for Forbes, Space.com, Live Science, Techradar, T3, BBC Wildlife, Science Focus, Sky & Telescope, BBC Sky At Night, South China Morning Post, The Guardian, The Telegraph and Travel+Leisure.

As the editor for When Is The Next Eclipse, he has a wealth of experience, expertise and enthusiasm for astrophotography, from capturing the moon and meteor showers to solar and lunar eclipses.

He also brings a great deal of knowledge on action cameras, 360 cameras, AI cameras, camera backpacks, telescopes, gimbals, tripods and all manner of photography equipment.