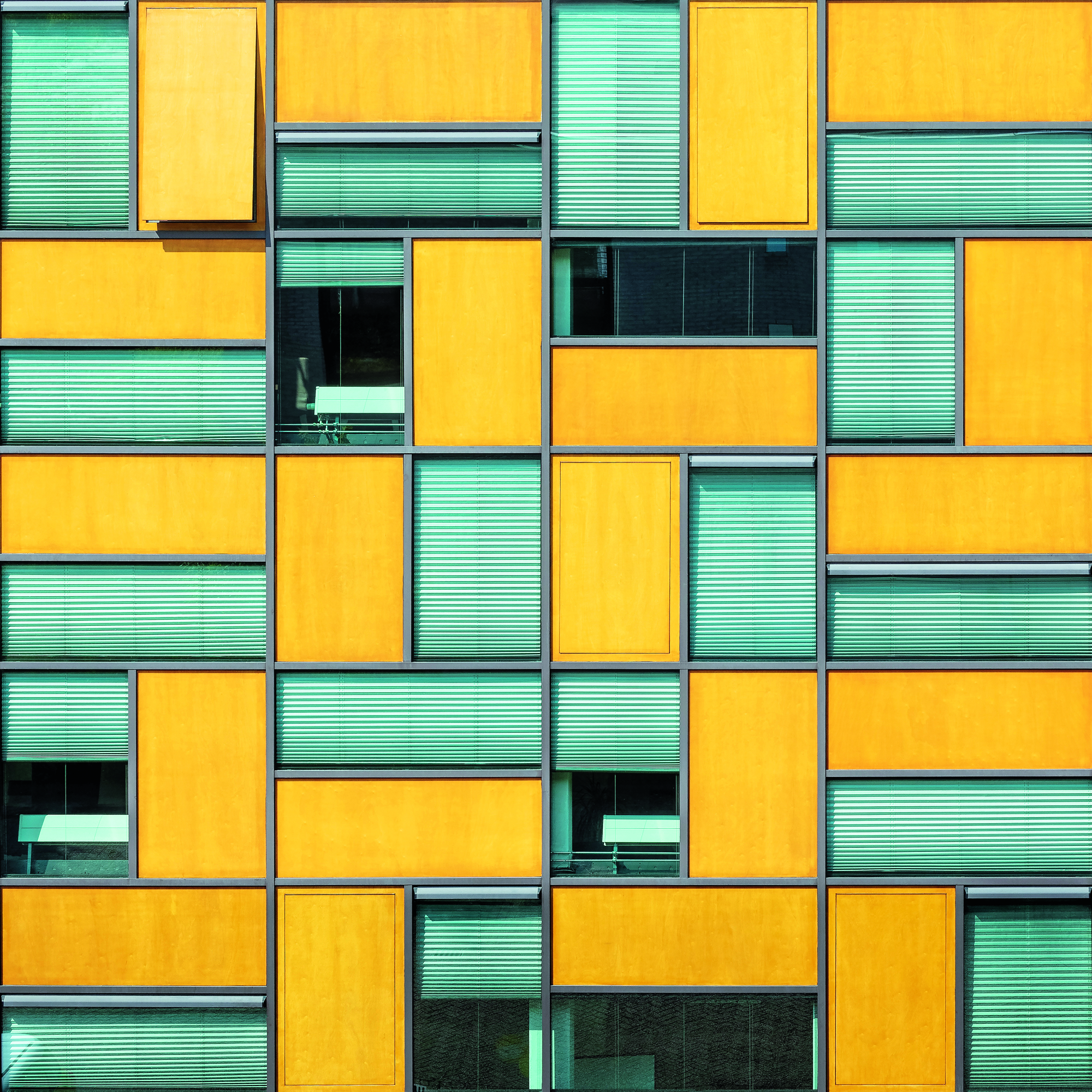

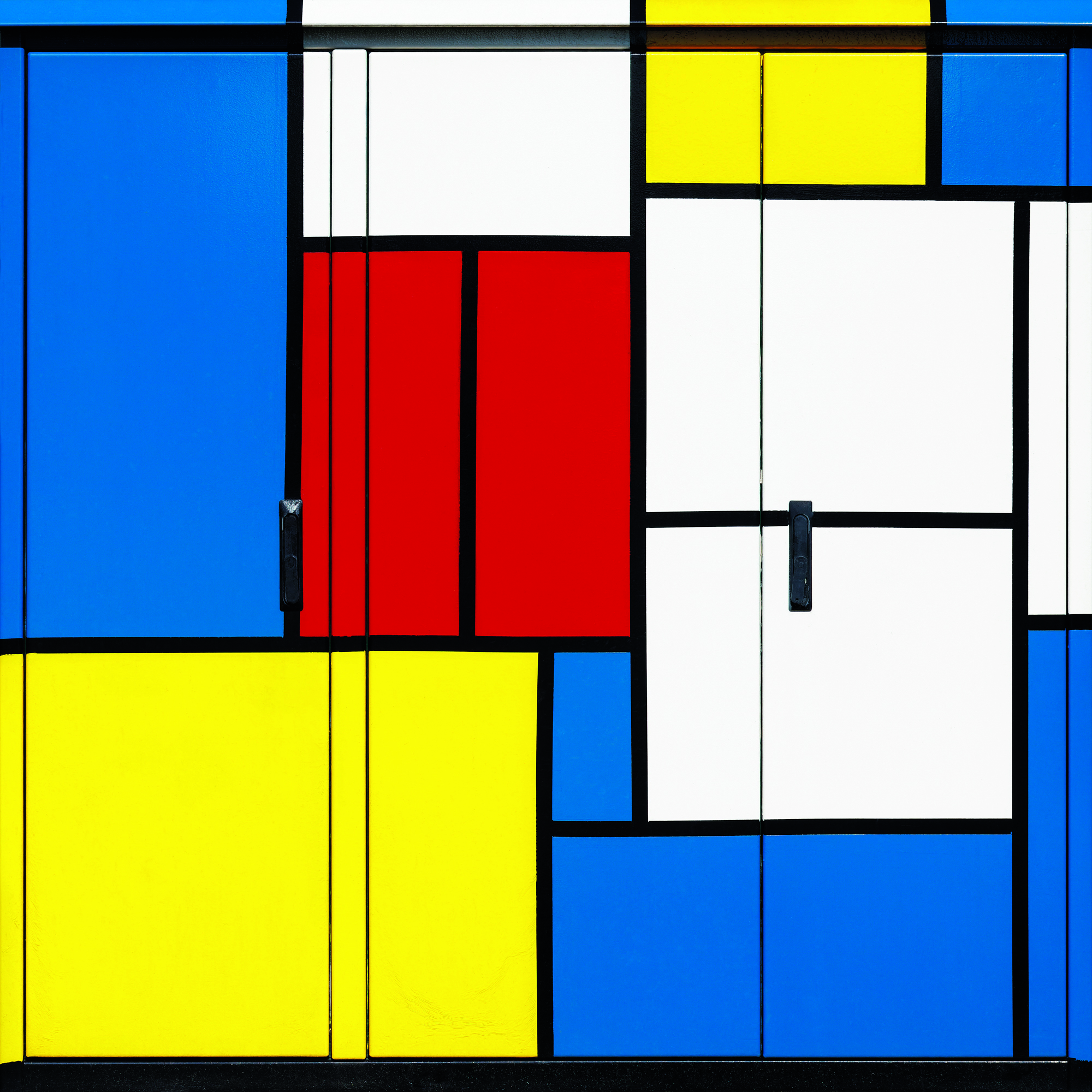

Chris Fraikin‘s photographs capture the beauty of industrial buildings

The Dutch photographer has just re-published ‘Archtracts’, a book of mimimal-styled studies of architectural details

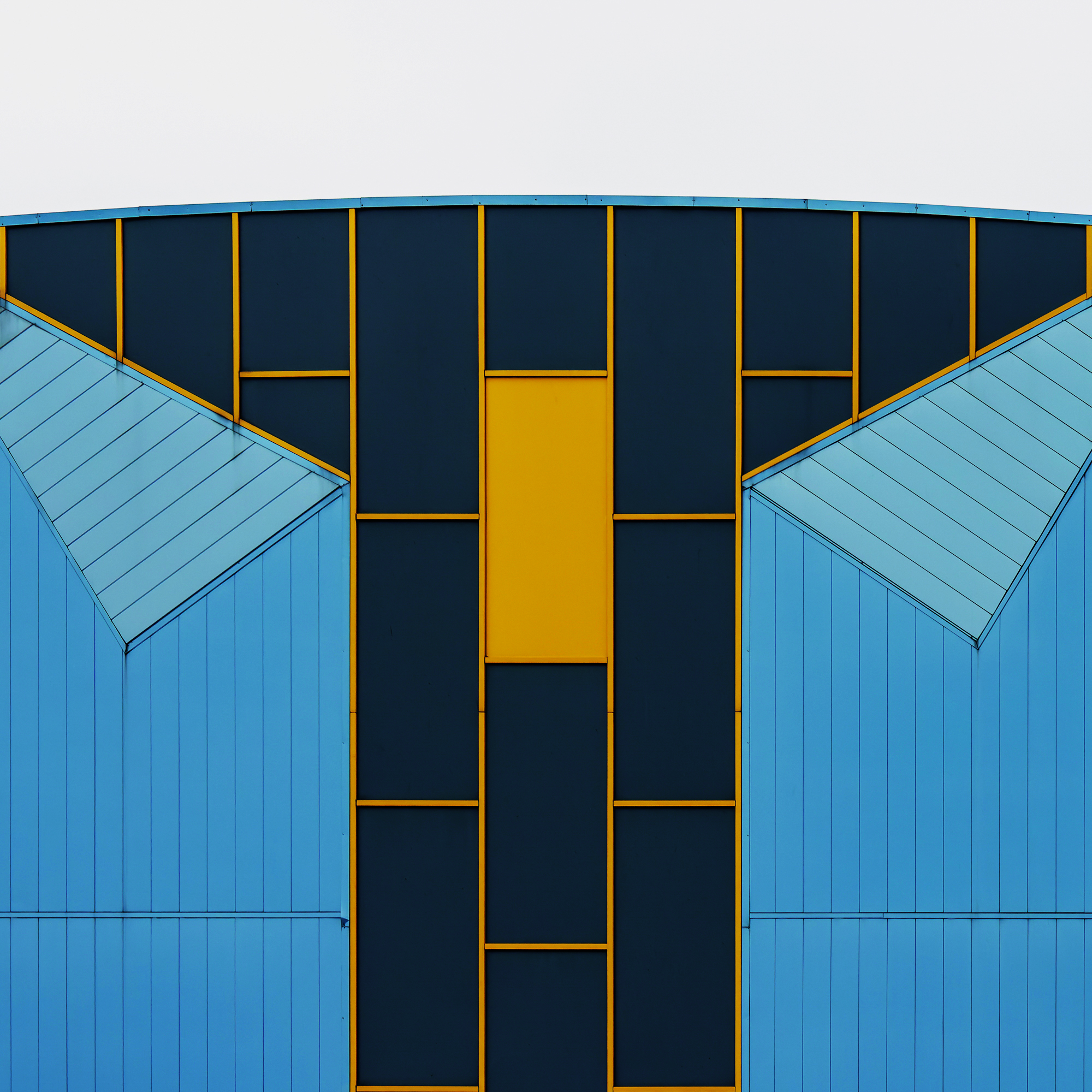

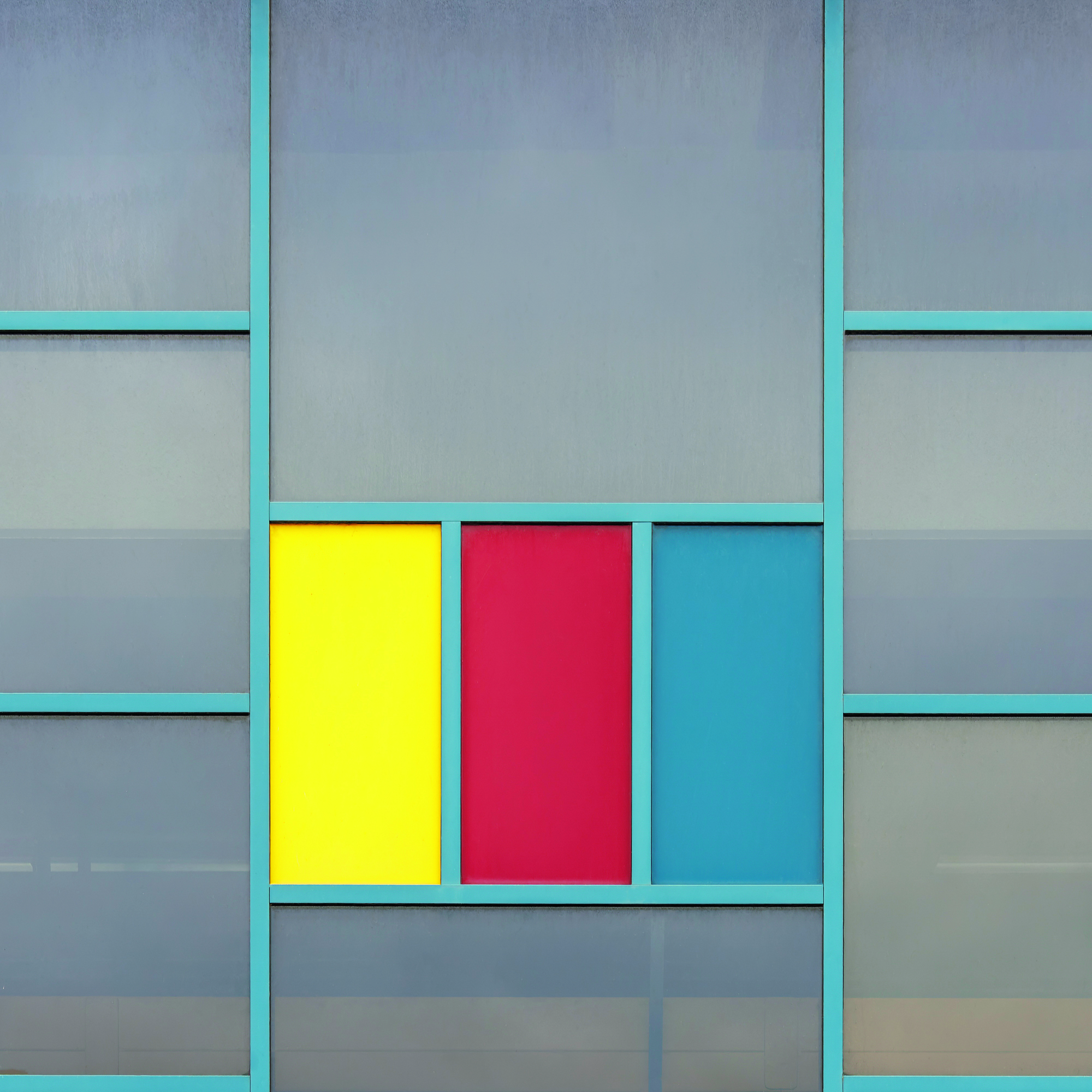

Chris Fraikin’s photographs of buildings feature strong lines, geometric shapes and striking colors and call to mind the work of the famous abstract artist Piet Mondrian – perhaps there’s something in the water in the Netherlands, as Fraikin and Mondrian are both natives of that country.

But while Mondrian’s works were produced in a studio, the canvases that Fraikin chooses are outdoors and in the built environment: industrial buildings and factory sites that were designed to be functional, but which on closer inspection often also have a certain amount of visual appeal hiding in plain sight.

• Canon EOS R5

• Tamron 150-600mm F/5-6.3

• Canon EF 70-200mm f/4

• Tamron 24-70mm F/2.8

• Canon EF 16-35mm F/2.8 L USM

Producing photographs in this vein is something that Fraikin has only been doing seriously since 2015, and was a reaction to becoming disillusioned with photographing live music. He was looking for a new creative outlet and eventually discovered it by photographing buildings.

As ‘Archtracts’, a book containing these contemplative, minimalist architectural works, gets a second printing, we caught up with Fraikin to discover more about this long-form project and how it began.

Despite his age (born in 1958) Chris Fraikin from The Netherlands is still a newcomer to the art of photography. He was educated at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, where he studied graphic design in the seventies. He built a professional career for forty years in succession in the graphic, the IT and the music industry. In 2014 he decided to focus more on photography. He attended workshops and made several photo tours as well in The Netherlands as abroad. Besides projects of all kinds, his current field of interest is what he calls ‘archtracts’: minimalistic extracts of architectural and urban objects. He mostly roams at industrial sites to discover the objects which are photographed in a contemplative way.

Can you describe your photographic style to someone who has never previously seen your work?

I call my works ‘archtracts’: minimalistic extracts of architectural, urban and industrial objects.

I mainly shoot in industrial areas – usually in the Netherlands – where almost all buildings seem to be nearly the same, because they are mainly built for functional content rather than beauty.

But if you take the time to open your eyes, you will often discover very interesting details in the shape, proportion or colour schemes in these buildings.

What’s the appeal of photographing architecture – is it seeing beauty in everyday structures?

Seeing the beauty in everyday structures is the attraction that led to these works. It is more or less a coincidence that I chose architectural objects.

An advantage of an industrial estate is that you have a lot of buildings together, so you can get into a flow to recognise many of those distinctive elements that you are looking for.

What are the most important factors you consider when composing an image?

When I am in the field and I am attracted to a detail, I must first filter out the environment around it in my mind in order to be able to properly assess the composition.

When I decide to take a photo, I only really think about the typical considerations, such as: do I have the right position to capture the image optimally; do I have enough in-frame for the perspective corrections in post-processing; are there no annoying reflections in windows; is everything in focus, and did I set the exposure settings correctly?

But the ‘real’ composition starts in post-processing. There, I determine whether the image will be used in a square (this is usually the case) or rectangular format, and at that moment I determine the crop to achieve good balance in the composition.

What advice would you give someone who wants to shoot your kind of photography?

First, understand the difference between minimalist photography and shooting details.

Minimalist photography is about ‘less is more’ and is much more about executing a well-balanced composition technically than the subject being chosen. In addition: look, look, look, shoot, shoot, shoot.

They often ask me how I manage to do it every time. You naturally develop an eye for it. Just think about photographing purple things.

At first you have to search a lot to find something purple, but before you know it the whole world seems to be purple.

To get the photos, do you need to be quite obsessive – going out in all weathers, early starts, with long, patient waits for the right conditions?

To get the photos, do you need to be quite obsessive – going out in all weathers, early starts, with long, patient waits for the right conditions?

Often, landscape photographers want to see beautiful skies and prefer shooting in the blue and golden hour, while architecture photographers want bright, sharp light with nice tight shadows.

Cityscape photographers often want to create nightscapes or busy streets with light trails from the passing cars.

For my type of photography it doesn’t matter that much. I only want to shoot in daylight, and not when the buildings are wet from the rain.

A possibly cloudy day, or a sunny one that gives a lot of reflections on windows, for example, are not conditions for the images I make, but additions to the compositions I create at that moment.

You’ve only been taking photographs seriously since 2015, and have made a lot of progress since then. What do you attribute this to – a naturally good eye?

You don’t necessarily need to have a good eye, I believe, but that you get it automatically by doing the same thing very often and also critically assessing your results afterwards in order to be able to develop them further.

What do you think sets apart an ‘OK’ architectural photograph from a ‘great’ architectural photo?

In my opinion, a ‘great’ photo differs from an ‘OK’ photo by having a good composition under the right lighting conditions with no distracting elements in the photo. Perspective should be properly corrected and the image should be razor sharp.

How do you find the buildings you photograph?

I use Google Maps to virtually visit cities and see if they have decent industrial areas. If this is the case, then I use Street View to view a number of streets to assess whether the buildings are to my liking.

After selecting the city with its industrial areas, I prepare a route to visit all streets as efficiently as possible and not to skip parts of the industrial area.

Are there any well-known buildings you would most like to photograph?

There is plenty in the architectural field that interests me to photograph. Think, for example, of the Expo 92 buildings in Seville, the skyscraper landscape in New York, and the colourful buildings in Miami and Burano.

But that is separate from the long-running series I am currently working on: after all, this is all about details, and the beauty of an entire building is not relevant to me at all at this moment.

Which cameras and lenses do you use?

For my minimalist work, I use a Canon EOS R5, a Canon EF 70-200mm f/2.8 and a Tamron 24-70mm f/2.8.

In addition to these, I also shoot with a Tamron 150-600mm f/5-6.3, a Canon 16-35mm f/2.8, a Sigma 105mm f/2.8 macro, an Irix 15mm and an Irix 11 mm.

Read more: The best Canon cameras in 2022

You said that the ‘real’ composition starts in post-processing – how much editing do you do?

The amount of editing depends on the work involved. My workflow is as follows: I import my photos with DxO PureRaw into Lightroom. PureRaw automatically corrects the captures during import for sensor and lens aberrations and chromatic aberration and has the very best noise reduction you can imagine.

Then I make the usual adjustments in Lightroom: white balance, exposure, highlights, shadows, whites, blacks, and so on. When this is done, the image goes into Photoshop.

First, I use DxO ViewPoint to correct the perspective because I want straight horizontal and vertical lines in my work, then I accurately determine the composition and crop the photo. The next step is usually the most intensive: retouching.

Buildings on industrial sites often contain quite a bit of bird droppings and other contaminants that have to be removed from the image. At that time I also eliminate any details and irregularities that require too much attention – some photos can require 300-400 corrections.

Before returning to the finished work, I sharpen the end result with Topaz Sharpen AI.

Read more: The best deals for Adobe Photoshop CC and Lightroom

What’s the greatest challenge you face when creating your kind of photography?

If the series of images you make – which is the case with me – already spans more than 5,000 works, the biggest challenge is to stay focused, because at a certain point the repetition also hides in the details and you can produce shots that are less and less unique. Yet, you want to prevent the repetition of previously made images.

Was it difficult to select the images for the ‘Archtracts’ book? How many didn’t make it?

Actually, this is already the fifth coffee table book I have published, but the first to be published by invitation by Snap Collective Publishing – the first four books were self-published.

It was not difficult to make a choice from the available works, because all my works were in principle satisfactory.

The selection of whether a work is satisfactory is already made the moment I complete a shoot; at least 60 per cent of the photos I take will end up in the trash.

The selection for a book focuses more on balancing the subjects of the details photographed and determining the order in the book.

Of the more than 5,000 works I have produced, about 1,000 have now appeared in a book, but that does not mean that the remaining photographs are going to lose out. Perhaps some of these photos will be included in a future book.

Do you know what the building owners, or the architects, think of your archtracts?

No, but simply because I don’t tell them that I have photographed details of their buildings. I do have quite a number of architects among my followers on Instagram, though, and Magazine Business Park, a Dutch trade magazine about industrial estates used some of my work on its front cover for a year.

What will you be working on next?

I’m not thinking about that at all – there is still plenty within this subject to photograph. But there will come a time when I think this project needs to come to an end and only then will I start thinking about my next project.

If I were to engage in that thought now, there is a chance of diluting my focus on ‘archtracts’.

Buy ‘Archtracts’ by Chris Fraikin

‘Archtracts’ by Chris Fraikin (hardcover, 168 pages) is published by Snap Collective Publishing (ISBN-13: 978-1-914569-44-9) and is available now, priced at £61/€69.90.

Click here to visit the Snap Collective Publishing website.

Read more:

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

How to shoot amazing architectural images

The best mirrorless camera in 2022

The best tilt-shift lenses for shooting buildings

Digital Camera World is the world’s favorite photography magazine and is packed with the latest news, reviews, tutorials, expert buying advice, tips and inspiring images. Plus, every issue comes with a selection of bonus gifts of interest to photographers of all abilities.

Niall is the editor of Digital Camera Magazine, and has been shooting on interchangeable lens cameras for over 20 years, and on various point-and-shoot models for years before that.

Working alongside professional photographers for many years as a jobbing journalist gave Niall the curiosity to also start working on the other side of the lens. These days his favored shooting subjects include wildlife, travel and street photography, and he also enjoys dabbling with studio still life.

On the site you will see him writing photographer profiles, asking questions for Q&As and interviews, reporting on the latest and most noteworthy photography competitions, and sharing his knowledge on website building.

- Lauren ScottFreelance contributor/former Managing Editor