How I use my unique camera rigs to take spectacular aurora images

How ‘super panorama’ robotic rigs help photographer Nathan Myhrvold capture the northern lights in super-high resolution

“Every photographer strives to capture a particular vision of the landscape or the world around them,” says ex-Microsoft CTO turned photographer and chef Nathan Myhrvold of Modernist Cuisine Gallery. “But I'm definitely taking photographs that few others could take.”

Myhrvold isn’t being cocky because his photography of the aurora borealis – as featured in his latest Iceland Series – largely relies on homemade camera rigs that use two, three and even four Canon EOS cameras.

“I use these rigs because they allow me to take incredibly high-resolution and high-quality panoramic images, including subjects that have motion, like the aurora, which changes second by second.”

Myhrvold (pictured left) took his collection across a two-week trip in the spring during which he was able to capture glaciers, wild horses, the ocean, and other ethereal Icelandic landscapes – as well as the northern lights, but to get his unique look and a purposeful approach to panoramas was required because a single very wide-angle lens just wasn’t going to work. “That approach tends to both introduce distortion and limit your resolution, which limits your optical quality,” said Myhrvold.

Read: Where, when and how to shoot the northern lights

The panorama robot

For horizontal landscape panoramas, Myhrvold used one camera with either a normal or slight telephoto lens and a programmable motor. “That’s why we call it a robot,” says Myhrvold. “The motor moves the camera to different positions and takes a picture, in this case, multiple pictures from different positions.” He then stitches all of the photos together to make a large panorama. Since each image in the panorama is 45 megapixels, the end result is a very high-resolution image, though image overlaps reduce the maximum possible resolution somewhat.

However, this setup only works well for photographing static landscapes. For the ever-changing northern lights, a different approach was required. “The panorama robot that I typically use takes 10, 20, 30 seconds—even longer for some things—to shoot a picture,” says Myhrvold. “That’s fine in the case of a mountain that’s just sitting there, but if it's an aurora, which is moving fast, or a crashing wave, not so much.”

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The ‘super panorama’ robots

So instead of having one camera that gets moved to different positions, Myhrvold uses multi-camera rigs. They are outfitted with three or four identical cameras each with a 40-millimeter lens that are set up to be level with each other so that all the images are taken simultaneously and can then be stitched together to produce a high-resolution pano.

“Besides having the angles correct, which is done by very careful machining of metal brackets, my team and I also developed electronics that make sure that all of the camera frames are taken at exactly the same time,” said Myhrvold, who calls the set up “The Three Amigos”, though for the horizontal aurora photos he used the 4x40 rig, which is outfitted with four cameras with 40mm lenses.

“It allows me to take a picture with a fast shutter speed from two, three, or four different positions—depending on the context—at once.” For vertical photos of the aurora Myhrvold used two stacked cameras outfitted with 24mm lenses. He also had to have special carrying cases made because none existed for such a specialized piece of kit.

Capturing the northern lights

Long night shoots capturing the northern lights in Iceland were a mixture of automation and human control. “It would be nice if you could just set it, forget it, and go to sleep,” said Myhrvold. “But the aurora moves, so it can be active in one part of the sky and not active in another part of the sky.”

As soon as he sighted the aurora Myhrvold set the cameras to take picture after picture. “It’s almost like it’s taking a movie or a video frame except because there's not that much light, each exposure is fairly long,” said Myhrvold. “You’re probably talking half-second or one-second exposures, so you can't do 30 frames a second as you do with video.” Myhrvold generally took images of aurora for about a minute before they change and a new composition was required. He shot for several hours, which allowed him to capture the fast-moving aurora’s best displays and later select the moment with the most vivid colors.

Dealing with moonlight

The moon can be a curse for astrophotographers, bleaching the night sky and making it harder to capture faint aurorae. However, the moonlight also illuminates the landscape. “If there’s a very faint, weak aurora, having the moon out is not good,” said Myhrvold. “But if there is a strong aurora—as I was fortunate enough to find in Iceland—the moon gives you just enough light that, with long exposures or by stacking many individual exposures, you can simultaneously get a really good picture of the foreground and capture the aurora overhead.” The theory applies to capturing the Milky Way or starfields above a landscape.

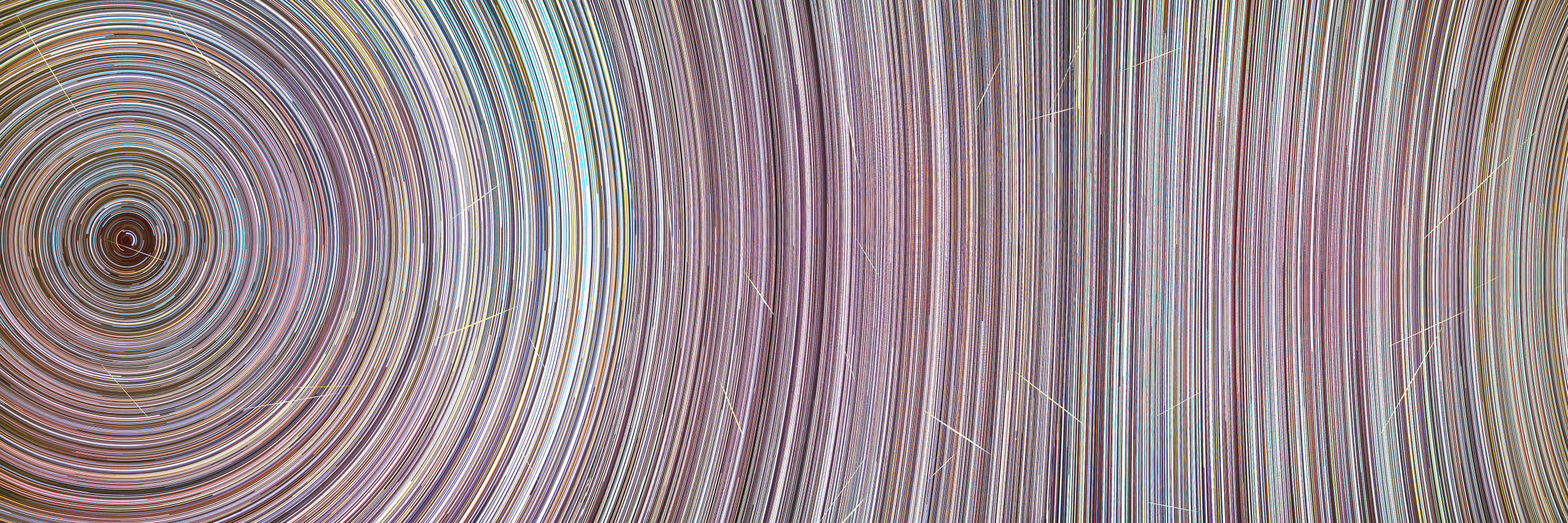

Star trails and meteor showers

For his earlier Cosmic Nightlife collection (which you can find in his online gallery), Myhrvold has also used his custom camera systems to capture the night sky without aurora and developed an entire astrophotography series. Here the emphasis was on wide. Myhrvold and his team designed and built a custom bracket that precisely positions three cameras with 24mm lenses to create panoramas with a 3:1 aspect ratio. That was specifically for a wide-angle star trail, but for images during the Geminid meteor shower, he needed something even wider. So he added a fourth camera to his custom rig, designing the 2x2 array to have a field of view nearly as large as a single 20mm lens.

Why not just use a 20mm lens? With this setup, he was able to get 16 to 32 times the sensitivity, much higher resolution and less edge distortion—something wide-angle lenses always introduce.

When and where to photograph the aurora

Although the aurora has been seen a long way south in recent months (because of something called solar maximum), it’s rare. They’re most dependably seen around 65º to 70º North latitudes in Alaska, northern Canada, Iceland, Lapland (northern Norway, Sweden, and Finland) and northern Russia. Patience is required, “You get good aurora about half the nights of the year and wind up having a clear night only about one in every three nights, so you might get a shot one out of every six nights,” said Myhrvold, who even on a good, relatively clear night is still looking for a hole in the clouds. “Typically in Iceland that breaks in the clouds is part of a weather system that's moving over you pretty fast so you are constantly scanning satellite photos and weather predictions.”

On this trip to Iceland and on previous trips to northern Canada and Alaska, Myhrvold says he’s spent many weeks trying to get aurora photos and wound up with many hours of good photos, but it’s largely a roll of the dice. “Photographing the aurora is a bit of a luck of the draw—sometimes we would deliberately set out to find the aurora and we'd get skunked,” he said. “But when it happens, it's just magical.”

Read more:

Astrophotography: How-to guides, tips and videos

Astrophotography tools: the best camera, lenses and gear

The best lenses for astrophotography

The best star tracker camera mounts

The best light pollution filters

Jamie has been writing about photography, astronomy, astro-tourism and astrophotography for over 15 years, producing content for Forbes, Space.com, Live Science, Techradar, T3, BBC Wildlife, Science Focus, Sky & Telescope, BBC Sky At Night, South China Morning Post, The Guardian, The Telegraph and Travel+Leisure.

As the editor for When Is The Next Eclipse, he has a wealth of experience, expertise and enthusiasm for astrophotography, from capturing the moon and meteor showers to solar and lunar eclipses.

He also brings a great deal of knowledge on action cameras, 360 cameras, AI cameras, camera backpacks, telescopes, gimbals, tripods and all manner of photography equipment.