I've got the best Canon cameras – but my best work comes from the urge to tell a story

It's often best to keep things simple. I captured my childhood hero Al Worden in the unlikeliest of locations using just a 50mm lens

On July 26, 1971, a five-year-old me is watching the launch of Apollo 15, one of the most complex missions of the entire Apollo space program and one of the first I can remember. As the Saturn Five rocket clears the tower, my Dad and I are glued to the tiny black and white TV set.

Dads’ passion for all things space was infectious and it left me with a sense that if we can put human beings on the moon, we can do anything, I can do anything! My Father and I shared this love and fascination with the cosmos until he died of cancer, far too soon, in September 1998.

• This is the best lens for portraits

Almost half a century later and I’m lying on a sofa bed in our living room recovering from a broken ankle, from a swing ball accident (you read it correctly), sporting an impressive five-inch plate and eight screws. Sometimes in life, we get a break, and I’m not talking about my ankle.

Just then, a close friend phones to say that Al Worden (Apollo 15 Command Module Pilot and one of the three astronauts who sat on top of the Saturn Five rocket all those years ago), now aged 87, will be at Excel, London next week and would I like to meet him and shoot his portrait? Without hesitation, I say yes, and call my wife, who immediately knows what this means to me and reassures me we can do this.

• Apollo remastered: how 35,000 photos were breathtakingly restored

Given my limited mobility, the next issue should be kit choice and yet for me, this isn’t a challenge at all. It’s October 2019, and I’ve been shooting with the Canon EOS R system for over a year. The decision is simple: my Canon EOS R body and RF 50mm F1.2L USM. Since first using the EOS R system and the 50mm lens for the R System launch, I have used very few other Canon lenses. It's perfect for so much of what I shoot and especially good for portraiture.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

After all, if 50mm is good enough for Cartier Bresson then it’s good enough for me! Add to this a couple of batteries and a 1 x 1 Fomex bi-color LED with softbox and grid. With everything fitting easily into my Billingham Hadley Pro Large bag, there’s even room for a small Manfrotto deflector and my laptop.

Photographing my hero (a last-minute lighting fix)

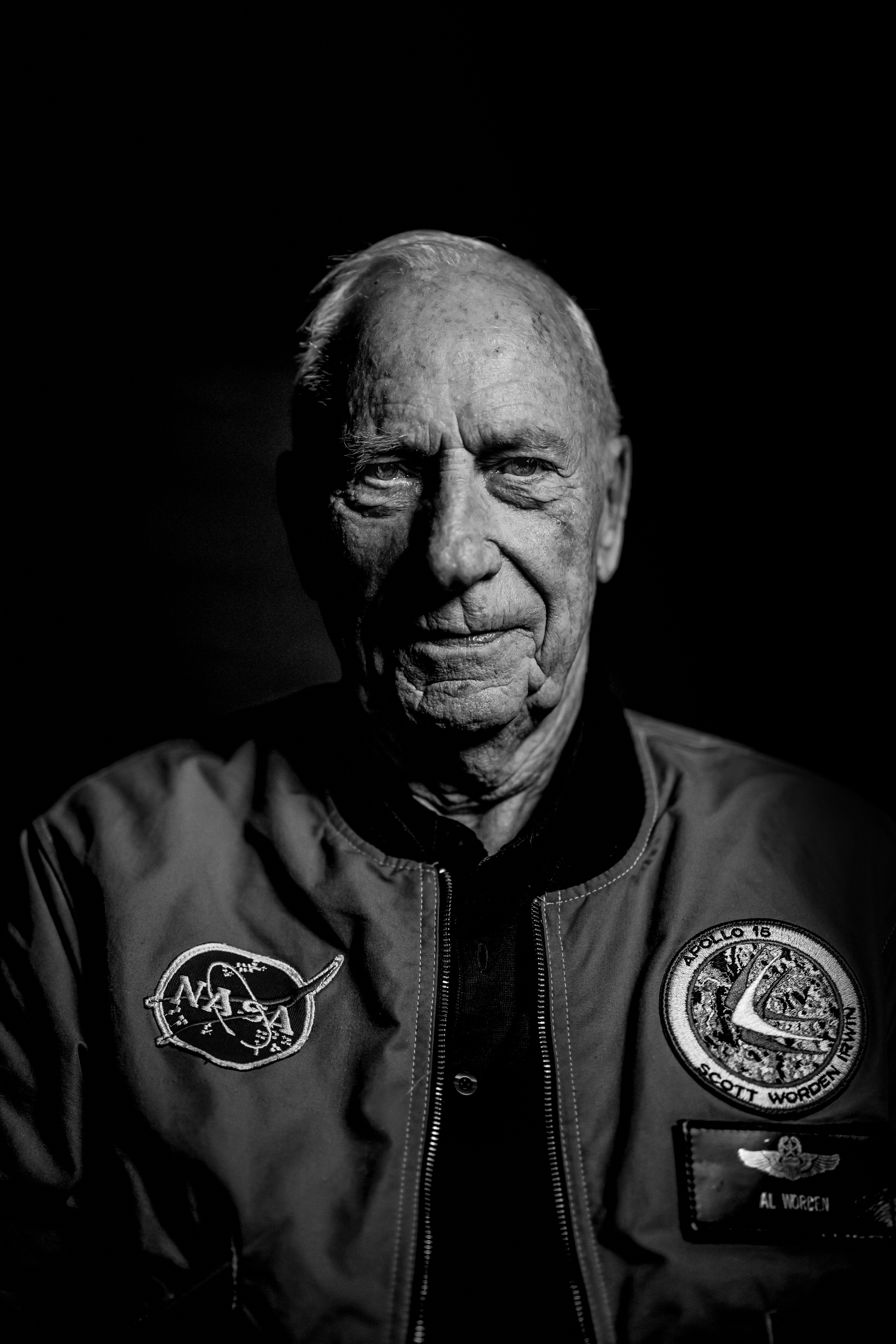

Seven days and half a century later I’m standing in front of my childhood hero. He is everything I had been told he would be, and at 87 he’s showing no signs of slowing down. Still lean, with thinning white hair, he’s wearing his light blue flight jacket with astronaut wings, Apollo 15 mission and NASA patches. But it’s his eyes that speak first: intelligence, experience, empathy, sensitivity, and understanding.

He is relaxed, charming and witty, with an ever-present smile and infectious regular laughter. I literally have to pinch myself. Al is only one of twenty-four human beings to have flown to the moon, orbiting it 74 times, and holding the record for being the most isolated human being in history. When his crewmates roamed the lunar surface, he was 2,235 miles away from them and nearly a quarter of a million miles from any other living thing.

He is sitting at a desk signing autographs and it’s at this point that I suddenly wake up to the fact I have this one chance to shoot a picture fifty years in the making. All I can think of is how terrible the lighting is. He is under fluorescent light and his eyes are in shadow, the background is confusing, and it would be impossible to shoot a meaningful portrait here.

Having said hello and exchanged pleasantries, I immediately start to assess my options. I look across the huge expanse of the Excel exhibition hall and literally right next to Al is a planetarium tent, large enough to hold twenty or more people as they cram inside and look up at a projected night sky.

Without thinking I hobble over and negotiate its use for the fifteen minutes it takes for the projector to cool down between shows. It may be great at showing the cosmos, but right now it’s going to be even better at being a blackout studio. Al quickly agrees to join me and we head in.

Creative collaboration and a meaningful portrait

Al is 5ft 10 1/2 and my wife, who is doubling as my lighting assistant, is five feet tall. I decide to sit Al on a stool whilst my wife holds the 1x1 light panel with soft box and grid as high as she can over his right shoulder. My inspiration for portrait lighting comes from well before the advent of photography. I’m drawing on the work of Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Vermeer, and my favorite local 18th-century painter Joseph Wright of Derby, whose work I first saw aged nine and which gave me a lifelong passion and obsession with light.

For me, portrait photography is not about the technical as that needs to be muscle memory!... it’s about the connection we make with our subject and this shoot is no exception and there is very little time.

I’ve found that when I share my ideas for a shoot with the person I’m shooting, it encourages a form of creative collaboration and helps ensure better final results. I explain to Al what I’m trying to achieve. I want meaningful portraits, beautifully lit and that tell a story. No pressure then!

He quickly picks up on what this means to me and obliges, he’s all business and so am I. Al played a key role in bringing the ill-fated Apollo 13 crew back to Earth safely and I quote “steely-eyed missile man”, a term used for an astronaut or engineer who quickly devises an ingenious solution to a tough problem while under extreme pressure, and he looks steely-eyed straight into the camera and it's immediately working.

I take a low angle, looking up at my hero both physically and metaphorically and I ask him to look up and left, I shoot close-ups of his mission patches, astronaut wings, and NASA insignia, as these will give me a series of narrative pictures.

Time is ticking and with just minutes left I announce I want to try one more shot. Two days beforehand, I’d seen a small moon globe light pop up in my Instagram feed and thought this could make an excellent prop. Switching it on, Al holds it in his left hand, looks at it with what I would later realize was introspection, and in just a few seconds I shoot several shots, and then it’s over.

Over the moon

This final image gave me everything I was looking for, Al, the moon, his mission patch and astronaut wings. It tells the story in a single picture or as I like to term it, a single-image narrative. It’s as if he or some part of him is still orbiting the moon and he is looking back at this moment through time.

After the shoot, I am satisfied with my decision to keep things simple. Especially, sticking with a single lens. 50mm is perfect for both close-ups and wides and it meant no time wasted on deciding on different focal lengths or lens changes. Both camera and lens perform brilliantly and my confidence in this liberating choice grows.

• What's the best 50mm lens?

Over lunch, I get to know Al and he never tires of answering my mountain of questions, all of which I’m certain he’d answered thousands of times before. He explains that a large proportion of his mission objectives included photography and how this led to one of the most extraordinary and memorable moments of his time in space.

Somewhere on the 240,000-mile journey home, he was spacewalking to retrieve a vital film canister from the service module, and when taking a break to look up, he realized to his left he could see the moon and to his right the Earth. “Now I know why I'm here. Not for a closer look at the moon, but to look back at our home, the Earth."

Before we leave Al signs his biography Falling to Earth and hands it to me. I record the moment with my smartphone and ask who his favorite photographer is, and with a wry smile he laughs and says “This guy right next to me".

Printing the final edit

Back home and my final edit is just five pictures. I post-produce the files in Adobe Lightroom, some in black and white and some in color. Being a graphic designer I’ve always had a passion for print.

Nothing can beat the tactility of ink on paper, for me, it’s still the best way to share my work and the one I have the most control over. At home, I have a digital darkroom and color-managed workflow, from calibrated Eizo monitor to Canon imagePROGRAF PRO 1000 and finally to Hahnemühle digital fine art, archival paper. I make a set of archival prints. Put them in a portfolio with a card and send them to Al and his family in Texas, a small but personal thank you for a day I will never forget.

Every portrait is a legacy for the subject and me

I believe every portrait I shoot is a legacy for both the subject and for me, therefore I throw myself all in, making the absolute most of and squeezing every once out of every opportunity. What I didn’t and couldn’t have realized at the time was that this would be one of, if not the last, professional portraits to be taken of Al. Less than six months later I found out the tragic news that Al had died. I felt incredibly sad and yet at the same time extremely fortunate to have met him, photograph his portrait, and spend quality time with him.

I post a series of messages of condolence along with the pictures on my social media channels, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn, telling the story and what this shoot meant to me. There are a lot of complimentary comments and messages from others who had met Al, some were even his friends.

And then to my surprise, I receive a message from Al’s daughter and her husband, along with a photograph of their living room wall. The wall is a tribute to her father and includes Apollo memorabilia, as well as close-up pictures of the moon shot by Al. To my amazement right in the middle of this gallery is my portrait of Al holding the moon globe. The message reads, ‘You did an amazing job of capturing Al. We love your work so much, one of the shots is literally the centerpiece of our Al display at home. The one with the globe is our favorite. It captures Al in all his introspection”.

Sometimes our best work comes from the urge to shoot and to tell a story, driven by passion and purpose and a belief that anything is possible. After all, if we can put human beings on the moon we can do anything, I can do anything!

Read more on this story by visiting Clive's website.

Special thanks to Al Worden, Heather MacRae (ESA / Ideas Foundation) and Vix Southgate and the British Interplanetary Society without whom this opportunity and shoot would not have been possible.

Read more:

Clive booth: why I've never shot manually on my Canon camera

These are the best Canon portrait lenses

What's the best Canon camera?

After a 20-year career as a graphic designer, Clive decided to follow his lifelong ambition and become a photographer and filmmaker. His use of prime lenses and selective focus along with natural, available, continuous and found light gives his work an atmospheric and ethereal quality. His unique style, along with constant experimentation with new technologies and techniques, has attracted numerous international clients, including fashion brands such as Hackett London, LVMH, H&M and beauty brands such as MAC Cosmetics and L’Oreal. He also works for such corporate giants as Asus, Intel, EY and Aston Martin. In his role as a Canon Ambassador Clive gives talks and workshops both here in the UK and across Europe. He is passionate about sharing his knowledge, experience, expertise and learnings with young people and collaborates on visual storytelling workshops for Canon's Young People Programme, Canon Student development program and is an advisory board member and teacher for the Ideas Foundation Charity.

- Lauren ScottFreelance contributor/former Managing Editor