Interview: Marilyn Stafford on photographing Einstein, fashion & refugees

Marilyn Stafford shares poignant stories from her years of experience as a photojournalist

Marilyn Stafford’s remarkable life spans almost one hundred years, from Ohio in the Great Depression by way of post-war New York and Paris to London in the swinging 60s and harsher 1970s, followed by “another life” in retirement on the English south coast.

She began her photographic career with an almost accidental portrait of Albert Einstein, before moving to Paris on a whim, where Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa became close friends. From the late 1940s until 1980, she was a pioneer of socially responsible photojournalism while also liberating fashion shoots from the studio into the streets and portraying the leading politicians, intellectuals and celebrities of the day. What unites all her images is her innate ability to tell a story that captures the human spirit.

Now in her mid-90s, she received the prestigious Chairman’s Award for Lifetime Achievement from the UK Picture Editors Guild in 2020, and later this year her work is being celebrated in a major new retrospective book.

Having experienced first-hand the difficulties of being a woman in what is still often seen as a man’s world, she is a staunch advocate of women documentary photographers through the Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage Award, sponsored by Nikon UK and now in its fifth year.

The deadline for this year's FotoReportage award is Monday 24 May, so this is your last chance to apply. The overall winner is awarded a grant of £2,000 and the runner up receives £500. All shortlisted applicants are featured on the FotoDocument website. The Award is reserved solely for female documentary photographers working on projects that are intended to make the world a better place and which may be unreported / under-reported.

As Marilyn says herself, “Many years ago a photographer in New York told me, ‘Photographers don’t grow old, they just grow out of focus’.”

How did your forthcoming retrospective book come about?

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

When I retired in 1980 I put all my images and negatives in little bags and shoe boxes under the bed. I figured that nobody would be interested in any of my work, as it was so of its time, so I forgot about it and lived another life. But it turns out a lot of the pictures are now rarities and they are wanted, so after several successful exhibitions in the last few years, I decided to put some of them into a book. We hit our Kickstarter target on the first day, and I’m overjoyed and really so grateful to all the people who have pledged to make it possible.

It documents a remarkable life as one of the great female pioneers of photojournalism. What sparked your passion?

I was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1925 and brought up during the Great Depression. I remember newsreels at the cinema of Franklin D Roosevelt pledging to help people on the breadline, and seeing Dorothea Lange’s photographs in LIFE magazine documenting the hungry migrant families displaced from the Dust Bowl. That project was part of Roosevelt’s Works Project Association, which helped quite a lot of artists I later got to know in New York – they’d been given work like painting post offices. So from an early age I was aware that horrible things could happen but also that something could be done about them if there was the will, and eventually it seemed to me that photography might be an answer, although that realisation only came a lot later.

What was your first camera?

It was a Kodak Box Brownie, and I can still feel of the serrated edge of the metal shutter lever. I took my first pictures with it on a family picnic in the country by a beautiful, crystal-clear stream. I remember suddenly feeling very moved to wade into the water and take a photograph of it splashing over the rocks, but when I got the pictures back, that depth of emotion wasn’t in them. It was just water and stone. I was so disappointed at not being able to express my feelings that it put me off photography for years.

Instead I concentrated on my acting – I’d started classes when I was seven and went on to study drama at Wisconsin University – because theatre did feel very expressive. However, it had its own drawbacks because you were only ever speaking somebody else’s words. I suppose it was above my comprehension at the time, but fundamentally I wanted to say something to change the world and make it a better place, and that did start to enter into the frame, both subconsciously and consciously.

How did photography regain a foothold in your life?

After university, in 1946 I went to New York to find my way in the theatre as an actress and singer, and to pay the rent I took a job assisting a photographer called Francesco Scavullo. At the time he was just doing catalogue shoots but he later became one of the biggest New York fashion photographers. My job was picking up pins off the studio floor – to make them fit, the models’ dresses were pinned tightly at the back, and when the pictures were finished the poor girls would give a big sigh of relief and all the pins would pop out. I also did my early apprenticeship in Scavullo’s darkroom – mixing chemicals, processing film, hanging negs up to dry. In 1947 a friend gave me an old Rolleiflex twin-lens reflex and taught me how to use it. It was a marvellous camera with a great lens, but it had its limitations – with a Rollei you’re either shooting from the other side of the road or you’re right on top of what you’re photographing. Still, I managed.

In 1948 you took what was to become the first of many portraits of famous people throughout your career, of Albert Einstein. How did you get this incredible opportunity?

Two friends of mine were making a short documentary about Einstein, in the hope he would speak out in it against atomic weapons – which he did. They invited me along for a day’s filming at his house in Princeton, New Jersey, and on the drive there informed me I’d be taking the stills, then handed me a 35mm single-lens reflex camera. I’d never used one before and I went into a panic.

When we arrived, Einstein himself opened the door, dressed in baggy pants and a sweatshirt, very gentle and welcoming. While my friends were setting up their movie camera, he sat down in a chair near the fireplace in his lounge and asked at how many feet per second per second the film went through the camera. The director explained and Einstein very sweetly nodded his head and said, “Thank you. I understand now.” That stopped me in my tracks. It’s not every day you meet genius and humility, and since then I haven’t suffered fools gladly. So I just did what I had to do – focus and get the shots. Unfortunately, the director kept all the negatives and I got just one large mounted print and three or four little headshots.

Why did you leave New York for Paris in the late 1940s?

It was because of male infidelity. The husband of a close friend was having an affair, and when she found out, she told him, “I’m going off to Paris and I’m taking Marilyn with me and you are going to pay for it.” Of course, I fell in love with Paris and decided to stay. By this time I was hooked on photography, so I would get on a bus every morning to the end of the line and wander around taking pictures. That’s how I found the Bastille slums, where I’d photograph the kids playing, but I wasn’t making any money from photography at this point. Then one night at a birthday dinner with expat friends, just after we’d finished singing happy birthday, a man standing behind me introduced himself as a theatrical agent and asked me to audition for an ensemble at a place just off the Champs Élysées called Chez Carrère. It was a very smart, very exclusive dinner club, and the only one in Paris Princess Elizabeth was allowed to visit. I said yes and got the job.

Did mixing in these circles open any doors photographically?

Chez Carrère was the place to be in Paris and I met many interesting people there, including Maurice Chevalier, Bing Crosby and Noël Coward – who asked me to audition for a play in London, then later telegrammed to apologise that it had been cancelled. In one of my many moves over the years his telegram was lost, along with several big boxes of photographs and other memorabilia, and I’m still sad about that. One evening I was invited to join Eleanor Roosevelt at her table, probably because I was an American. We spent some time talking but I never once thought about taking her picture. That’s a real regret, as she was the woman I most respected in the world. I still wasn’t really thinking like a photographer at this stage.

But I did get a few photographs of Édith Piaf. A young American singer and actor called Eddie Constantine, who’d joined the ensemble not long after me, translated some songs from English into French and took them to Piaf. She rather liked the songs and she rather liked Eddie and they became lovers. Every night she would come into the club to pick him up after work and we’d all go along to her house in Bois de Boulogne for breakfast. She had this great entourage living with her, including Charles Aznavour, and I joined them for about six weeks until she left for her next tour. One day we all went for tea at the Grand Hotel and I got some shots of her I really like. She was always being photographed in black and looking miserable, but here she was, wearing a very nice white pleated dress and laughing.

You later became friends with the Magnum co-founders Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. What effect did that have on your photography?

Bob [Capa] used to go to the lovely little bar at the front of the club most nights and we struck up a friendship. He was like a big brother to me. I was so impressed by his work but we only really talked about photography when I told him I couldn’t sing for a living for much longer because I was losing my voice. He suggested that I start work for his friend and Magnum co-founder David Seymour – Chim – but I said no way was I going to be an assistant to a war photographer. I didn’t want to go into a war zone. Both of them got blown up in conflicts in the end.

I met Cartier-Bresson through a mutual friend, the Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand, and I think because of that he took special care of me. He was like family. I was often invited to dinner at his house – he was married at the time to an Indonesian dancer called Ratna Mohini – and he became my mentor. I’d go out with him on shoots to observe how he worked. He was very tall and usually wore a hat, and when he brought his little Leica up to his eye, nobody noticed. All they’d see was me, this very small woman carrying a very large Rolleiflex at a time when no one really had a camera. Cartier-Bresson would look at the photographs I’d taken and instead of telling me what not to do, he’d make suggestions – “If you did it this way you’d get a different result”. He simply helped me to see.

He also helped me in 1958, when I went to the Tunisian border town of Sakiet Sidi Youssef during the Algerian War of Independence to photograph Algerians fleeing from the French bombing campaigns. After the French bombed Sakiet’s Red Cross hospital, I felt compelled to bring the plight of the refugees to public attention. When I got back to Paris, Cartier-Bresson looked through my photographs and sent a selection to The Observer. Two made the front page – my first front page – on 30 March 1958 and I was so proud of being able to highlight the refugees’ plight, as it wasn’t being widely discussed at the time.

How did life change after that?

I was five months pregnant with my daughter at the time and had to spend several weeks in bed recovering from the rough journey home. Not long after Lina was born, my then husband, who was a British foreign correspondent, was posted to Italy and so we left Paris for Rome. There I met quite a few artists and intellectuals, including the writer and painter Carlo Levi. He introduced me to a very interesting lady, Francesca Serio, who became one of my heroines – I have a few! She was an illiterate peasant and the first person to bring the Mafia to trial, for the murder of her son. I photographed her in my apartment and it’s one of my favourite portraits, because what she stood for shines through. I later travelled to Palermo for the trial but somehow misloaded the film, so I didn’t get a single picture of those men in a cage in the courtroom.

We then moved to Lebanon, where a local publisher asked me to do a book of photographs to promote the country as a tourist destination. I travelled extensively, recording everyday life, and because the results weren’t the Fifth Avenue or rural idyll-style pictures he’d wanted, he wouldn’t publish them. Many years later, a friend of mine showed the dummy to the Lebanese writer Mai Ghoussoub, who was co-founder of Saqi Books in London. Mai looked at the photographs and said, “This was my childhood.” And that’s how it finally came to be published in 1998, as Silent Stories: A Photographic Journey Through Lebanon In The Sixties.

During my husband’s next posting, in New York, I decided not to work while we were there because my daughter was starting school and it was all just too complicated. Instead I had a nice life shopping and watching Greta Garbo. She lived not that far from me on the East Side so I would see her in the street, and because I was furnishing my little apartment I would often go to Bloomingdale’s, which I adored, and she always seemed to be there at the same time. In the mid-1960s my husband was posted to the Soviet Union. I’d been told it wasn’t a good place for a woman with a camera. The marriage was on the rocks by then, so we separated – he went to Moscow, and Lina and I to London.

As an American, why didn’t you stay in the US?

Well, I wasn’t an American anymore. I’d taken my husband’s British nationality when I got married in 1956. Being with a foreign correspondent, you never knew where you’d be going next and some places wouldn’t let you in with an American passport. So being under the same flag had made life much easier, and it also now meant that living in England made the most sense, especially as I already had contacts with The Observer and a few other UK publications, plus some international ones, so I knew I’d be able to pick up some small jobs at least.

Was it difficult getting regular photojournalism work, in an era when women photographers were something of a rarity on Fleet Street?

Photography was still very much a man’s world, especially news. Portraiture and fashion were definitely seen as more suitable for women. Of course, I’d had experience in fashion studios – as well as in New York with Scavullo, in Paris I’d spent a short time assisting the American fashion photographer Gene Fenn in his studio – and I’d worked with a Parisian PR agency doing fashion commissions, where I’d take the model and all the clothes out in a cab onto my beloved Paris streets.

So in London, when I met a wonderful French fashion photographer called Michel Arnaud, we decided to set up a small fashion agency together called ASA – Arnaud Stafford Associates – and that little agency kept me going until I retired in 1980. We covered all the haute couture and ready-to-wear fashion shows in Paris, London, Milan and New York at our own expense then sold the images to the newspapers, so they saved money. The Observer was our only client for our first Paris season but we came back with five more, which was a wonderful start. It was exhausting work – sometimes up to ten shows a day – and I was never rich, but it provided a stable income that paid the bills and allowed me to do all the other photography I wanted to do.

What types of projects did you choose to pursue in your own time?

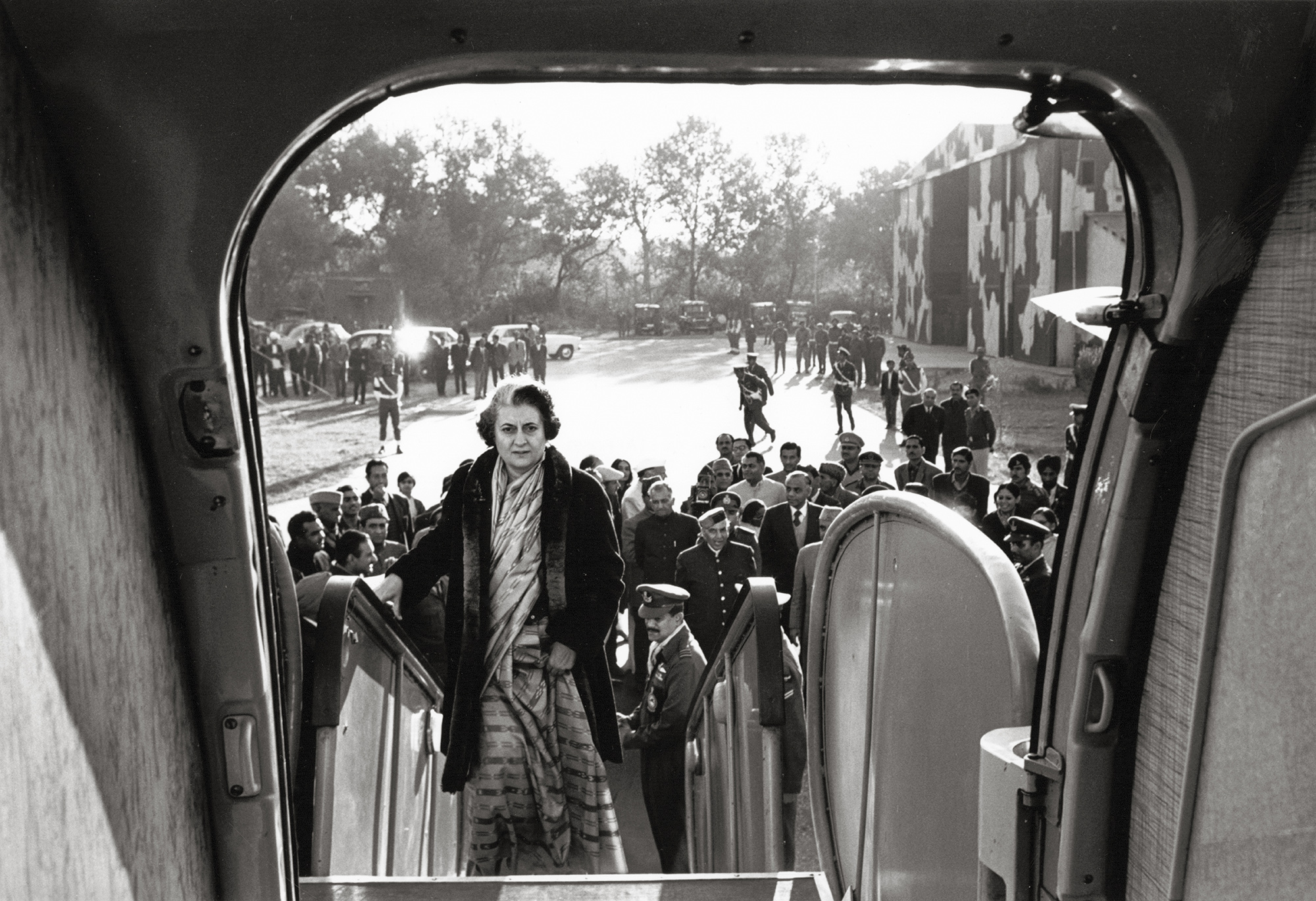

One of my first was a trip to India in late 1971 to photograph “a day in the life of the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi”. It wasn’t exactly a commission but a London magazine said they’d be interested in it. The first thing that happened when I arrived was that all my film was confiscated because it was assumed I’d be selling it on the black market. Then I got a message from Mrs Gandhi’s office asking me to change the time and venue of our first meeting, which proved impossible to do. And then she declared war on Pakistan and it turned out she’d wanted me there to take her photograph as she did it – so I missed that scoop.

My first meeting with her ended up being in early 1972, when the war with Pakistan had ended. We were on an aeroplane to Kashmir where she was going to start a big tour, visiting wounded soldiers and making speeches – and an added advantage for me was getting to see the Himalayas from the cockpit. In the end I spent around a month photographing her, and I was invited to visit her family in Delhi. Mrs Gandhi was very gracious, and later that year when I wanted to go to Bangladesh to do a report about the poor girls who’d been systematically kidnapped and raped by the Pakistan army, she was very encouraging. The story was eventually published in the Guardian and I raised £5000 to send to Bangladesh to help those women.

Just a few days after I returned to London, I was offered a staff job on a fashion paper. I turned it down. I’m not denigrating fashion – there is enormous creativity in it, and looking at beautiful design and beautiful fabric is always a pleasure – but having experienced such a terrible and traumatising reality, I didn’t want to get caught up in the fashion world. So I stayed freelance until I retired in 1980, doing the fashion work I chose, in order to support the photojournalism I wanted to do.

Do you have any particular favourite memories from that era?

I went back to India six or seven times, including a wonderful visit to the forest-dwelling Ghotal Muria tribe in Chhattisgarh. I still have a photograph of the little boy who used to come every morning and sit on the fence outside the schoolhouse where I was staying. He’d bring breakfast in a big leather bag – fruits from the forest, which I’d eat off a huge banana leaf. One morning my translator took me to visit a family hut. There was no one at home, but she said it would be fine to look inside. It was so small, about the size of a bathroom, and so neat, with a brushed hearth and a place to sleep and cooking pots hanging from the ceiling. And then suddenly this lovely young woman emerged from the forest shouting an apology for her “dirty house”. She ran in and picked up one single leaf from the floor and I thought, my god, it’s like going to my mother’s. Women are women everywhere.

Why did you decide to establish the Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage Award?

In the mid-1960s when I arrived in England, there were very few women in Fleet Street, and as a single mother I was caught between caring for my daughter and doing what the job was telling me to do. There are still issues around discrimination and unequal pay. Many women documentary photographers want to tell important, underreported stories but have to juggle family commitments and often have no funding or guarantee of a financial outcome. So I wanted to find a way to support these incredible women, and when I met the documentary photographer Nina Emett, everything fell into place.

Nina is the founder of FotoDocument, a social enterprise which showcases positive solutions to global issues through documentary photography. We set up a grant to support women photojournalists financially, but it’s about more than the money – it’s helping to give them confidence and exposure. Women make up the largest numbers in photography colleges, yet commissions are particularly low for women in photojournalism and advertising. Setting up the award was my way of redressing the balance. The more women documentary photographers there are in the public eye, the more they will be commissioned and eventually revered in the history books. We’re now in our fifth year, with Nikon sponsoring us for the third time.

How has your relationship with Nikon developed over the years?

I started using Nikon around 1970, when Michel Arnaud and I set up our agency. One day he said to me, “We’ve got to move to Nikon because the cameras are so good.” So we did. And I adored my Nikons. I found them very easy to use. Then in 2019, when I was being presented with the Exceptional Achievement in Photography award by Amateur Photographer – which was such a surprise and an honour – I was introduced to the lovely people at Nikon UK and discovered they are committed to developing women photographers. So we’ve been able to forge a very productive relationship and for the last three years they have generously provided the funds for my award and towards the management, judging and marketing. Above all, they provide encouragement, because they fully believe in what we are doing. It’s my hope this relationship will last for many, many years and become a legacy for me and my work.

What advice would you give to women wanting to make a career in photoreportage today?

I’d just say go for it. Keep fighting for the opportunities that exist, get out there and do some good work. It’s hard, but determination will get you there in the end. Talent is irrepressible and glass ceilings are there to be smashed.

The deadline for submissions to the Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage Award 2021 is Monday 24 May. https://fotodocument.org/fotoaward/

Marilyn Stafford: A Life In Photography will be published later this year by Bluecoat Press, priced £28. Find out more at www.marilynstaffordphotography.com

Read more

Best professional camera

Best Nikon camera

Best Nikon lenses

Best film camera

Best mirrorless camera

Best DSLR

With over a decade of photographic experience, Louise arms Digital Camera World with a wealth of knowledge on photographic technique and know-how – something at which she is so adept that she's delivered workshops for the likes of ITV and Sue Ryder. Louise also brings years of experience as both a web and print journalist, having served as features editor for Practical Photography magazine and contributing photography tutorials and camera analysis to titles including Digital Camera Magazine and Digital Photographer. Louise currently shoots with the Fujifilm X-T200 and the Nikon D800, capturing self-portraits and still life images, and is DCW's ecommerce editor, meaning that she knows good camera, lens and laptop deals when she sees them.