Interview: Maryam Wahid on judging photography alongside Rankin and HRH The Duchess of Cambridge

The award-winning photographer and judge on The Great British Photography Challenge shares stories of her identity, community and a millennial’s love for the film aesthetic

Maryam lives and works in the UK. She expresses the origins of the Pakistani community in her hometown Birmingham (UK) by exploring her deeply rooted family history; and the mass integration of migrants within the United Kingdom. Her work explores the female identity, the history of the South Asian community in Britain and the notion of home and belonging. Maryam has been commissioned to create photographs for The Guardian and The Financial Times, and was the Portrait of Britain Winner 2018. Last year, Maryam judged the photography competition Hold Still 2020 for the National Portrait Gallery, alongside her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cambridge.

Tell us more about your photography and the themes you explore?

I would describe my work as quite autobiographical. It’s based on my personal experiences, on my personal family history, heritage, cultural identity, and to some extent, my religious identity. I graduated from university in 2018, and it was only in my final year that I started to actually photograph and do what I do now.

You’ve mentioned the lack of diversity in higher education. But how has your career progressed since university?

When my final year came at university, a few changes were happening, even then. I had a visiting lecturer called Kate Peters who would come in. She’s a great practitioner, and it was just so refreshing to talk to her.

When I left university I won the Portrait of Britain Award, and that was because [Kate] pushed me to apply for it. She really pushed me with the self portraits, too. I was very hesitant and reluctant to explore them, because I felt very awkward talking about my culture and talking about women in my culture.

You need that one person to look up to, and she really was somebody I was inspired by. When I left university, I was also awarded a mentorship with Grain Photography Hub, which is a photography organisation in West Midlands, UK, run by a woman called Nicola Shipley. She became my mentor for a year. She’s an encyclopedia for how the industry works.

Did you find talking about your work hard at the beginning?

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

It was very difficult to start with. But because I had Nicola, I had a female mentor just telling me, “It’s okay. It takes practice, and y’know, just get on with it.” So I just threw myself in the deep end, which is like a lot of things I’ve done in my life.

I have learned that it does take practice, but I think a huge part of it is having people that support you. So that also goes back to the question about diversity in universities, because I really struggled there. The awkwardness came because I felt like nobody could resonate with migration themes.

Do you think shooting something so personal has helped you in your practice?

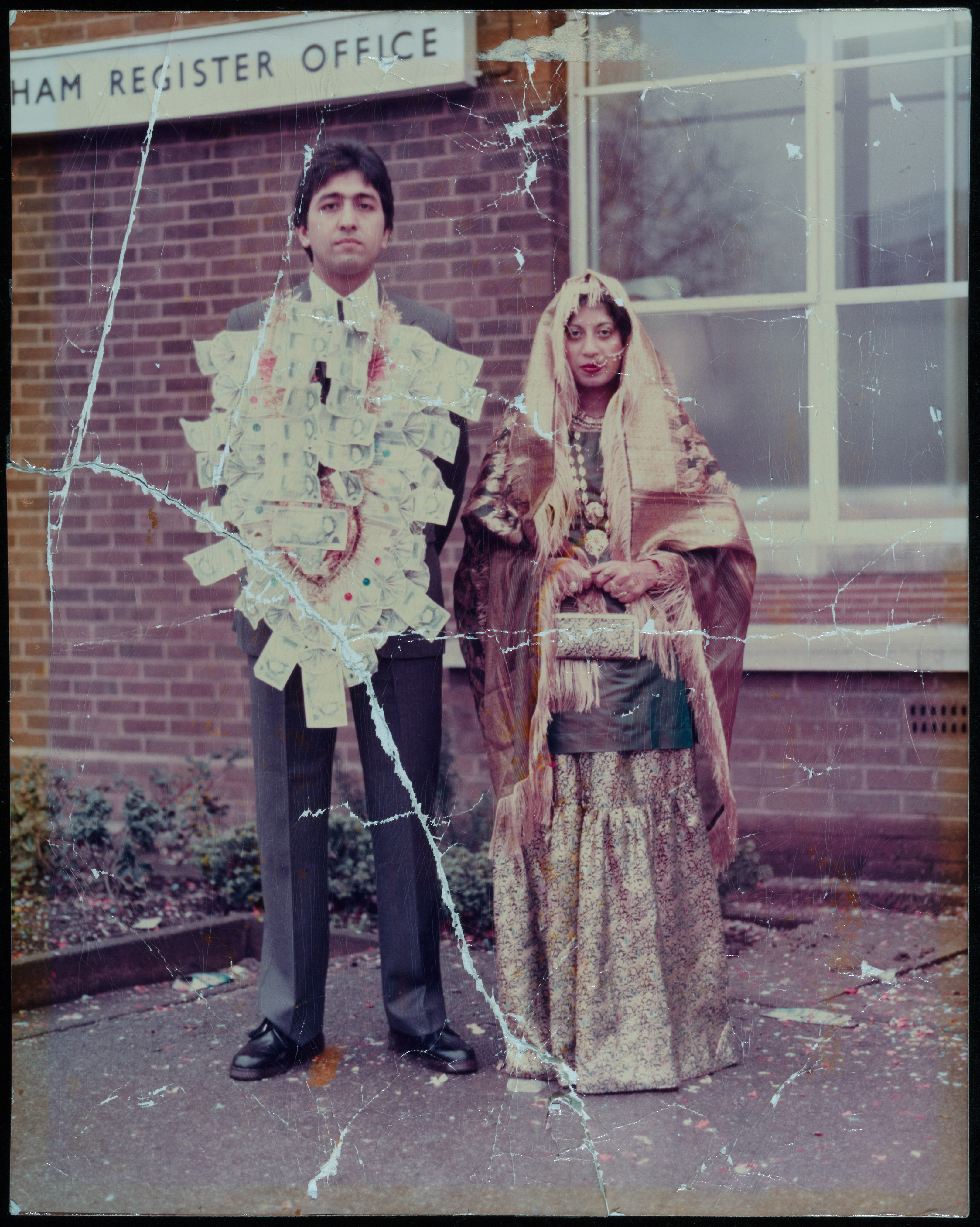

Absolutely. I’m exploring ideas within my own interests. It all started from looking at my family album. My parents were born in Pakistan; my father came here when he was six, my mum came when she was 18, and they got married in the 80s here. Looking through, I would find photographs of Pakistan in my family album and find photographs of England.

I embrace both cultures and both heritages, and when I was seeing these two places in the album, I found it quite fascinating. I started to explore why women and men are dressed in this particular way. I started to question and understand the real foundation of our community, of my community, in Britain.

Photography has really given me a sense of belonging. Again, there’s no sense of identity crisis at all, but it’s kind of made me feel like, “Wow, this is what my grandmother looked like”. And obviously when migration is involved, in history or in your own personal history, you lose certain information, certain histories and personal stories.

For me, it was particularly those women’s stories… knowing who my great grandmother was, for example. I’m obsessed with learning women’s stories, and then bringing them to life and retelling them.

There’s a real connection with your subjects. Do you plan shoots in advance, or are they more reactive to the subject?

If you look at my Hijab portraits, I plan those, and I’ll do things a bit more staged. Even the self portraits are all staged, as I was trying to feel like my mother might have done when she migrated to Britain. I wanted to perform in those spaces and actually feel like the migrant woman, which I did because everybody was staring at me like, “What the hell is she doing?”.

I’m into using mood boards to work out the aesthetic. I also plan how I want the audience to perceive the image. Do I want the person to be looking in the lens? Generally, it’s about knowing that gaze and what I’m trying to tell.

Do you look to other artists and photographers for inspiration?

I look at all kinds of stuff, to be honest. I look at paintings, and I love films in general, especially Asian films, Bollywood and all that. I’m so interested in the aesthetics, the fashions, and the styles and trends of the South Asian diaspora.

How was judging the National Portrait Gallery’s Hold Still 2020 competition?

It was a really great experience. I was on the panel with the Duchess of Cambridge, which was just really cool, but it was also very emotional going through the entries and seeing all these similar themes come out of them. I felt like I hadn’t seen all the sides of Covid, because I was in my house. I didn’t see people really struggling in hospitals, going to see their loved ones, standing outside their parents’ care home just to say hello to them.

You’ve also recently been on the BBC’s Great British Photography Challenge?

Yes, I was a judge on one episode. A lot of the individuals were hugely passionate about photography. I set a task for them and they were all very excited, and they all had different outcomes in the end, which was nice to see. It seems like a very exciting show. Rankin’s on it, and he’s such a cool photographer.

What are you working on at the moment?

My current project is called Zaibunnisa, and it’s the first project which I’ve shot in Pakistan. When I got there, I found myself capturing memories of stories from my childhood, today. With the pictures, I couldn’t help but see myself in Pakistan, in the sense of what my alternate life could have been like. The project is going to be shown in The Midlands Arts Centre next year.

Is it important for your work to be exhibited?

Exhibitions allow me to show my motivations in creating a project but also write captions and stories for the images. One of my goals is for art collections in Britain to have more contemporary South Asian art with context.

You recently shifted towards film from digital shooting. Why was that?

I started to explore film in my final year at university. I’ve always shot digital, but when I started to shoot film, I felt like I was getting a bit closer to my subject. I’m also often telling stories with history, and I loved how the film images looked. I don’t want to say this, but I’m saying it ’cause I’m a millennial... there’s a nostalgic feel to film, and that sense that you’re going back in time.

What’s next for you?

I would love to see my work in public and private collections. I want to give back, to mentor and teach photography – not just as a technical course, but about these things we’ve talked about. I love that feeling of being able to help creatives figure out complex thoughts in their head. I want to keep showing my work and shooting, to keep my own practice going.

Read more:

Opinion: There's more to photography competitions than just winning prizes

Food documentary photography wins Marilyn Stafford Award 2020

22 pioneering women in photography

Lauren is a writer, reviewer, and photographer with ten years of experience in the camera industry. She's the former Managing Editor of Digital Camera World, and previously served as Editor of Digital Photographer magazine, Technique editor for PhotoPlus: The Canon Magazine, and Deputy Editor of our sister publication, Digital Camera Magazine. An experienced journalist and freelance photographer, Lauren also has bylines at Tech Radar, Space.com, Canon Europe, PCGamesN, T3, Stuff, and British Airways' in-flight magazine. When she's not testing gear for DCW, she's probably in the kitchen testing yet another new curry recipe or walking in the Cotswolds with her Flat-coated Retriever.