“It was a beautiful thing and suddenly I felt the Leica was the right camera. Like certain guitars, it fits your hands, your body…” The Police's Andy Summers on his photographic passions

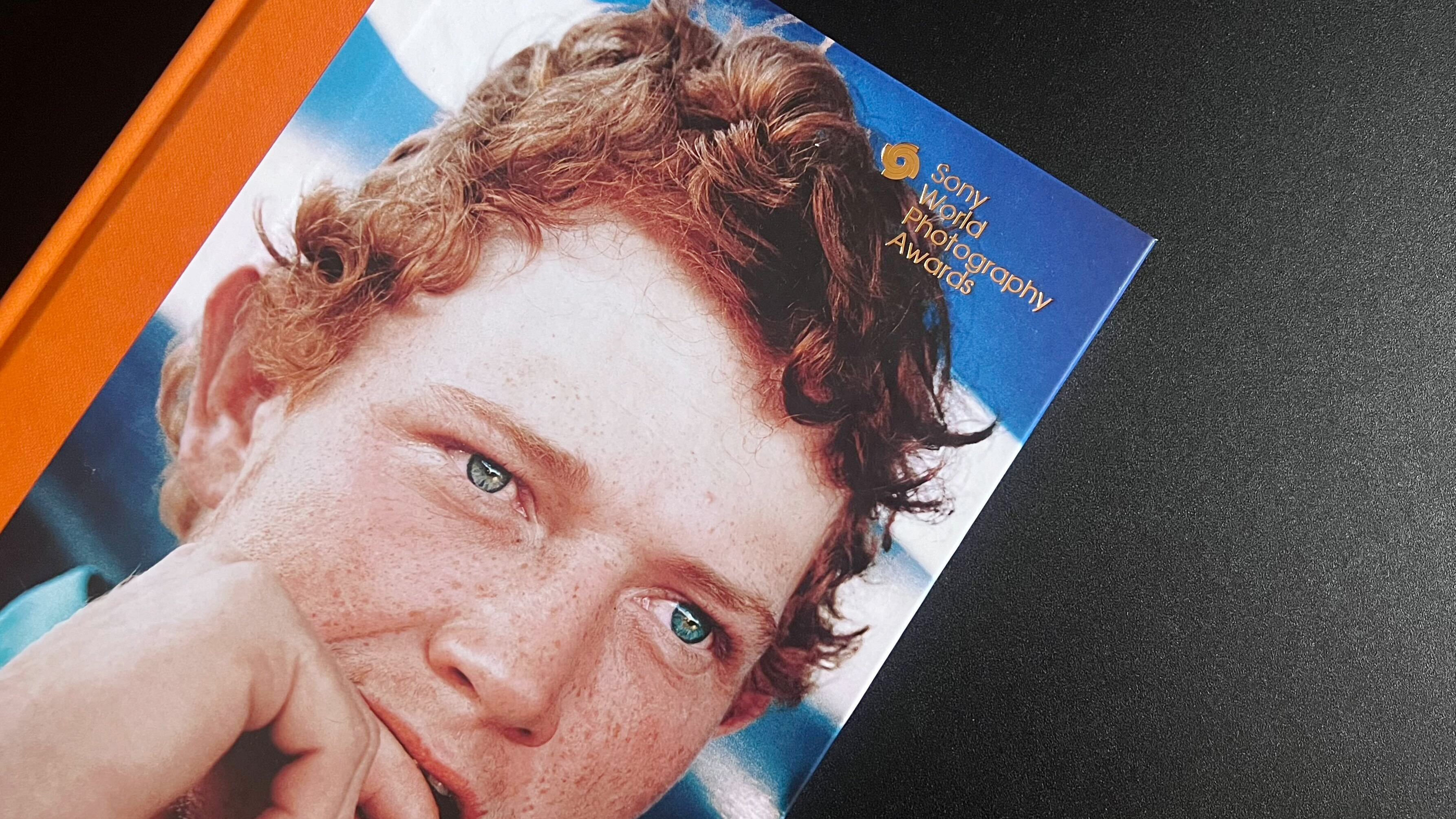

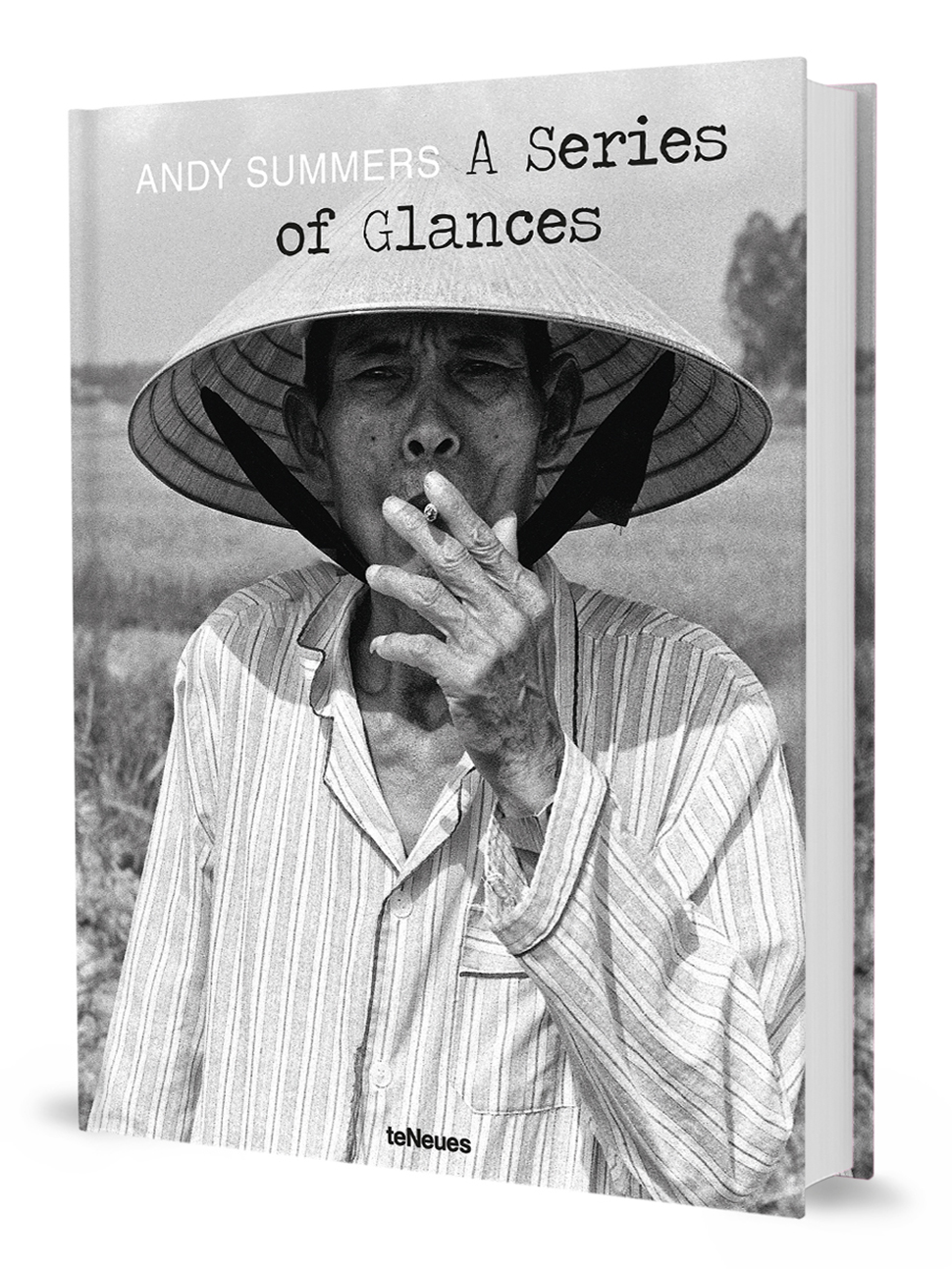

Former Police guitarist Andy Summers has a long-term passion for photography – and his best pictures appear in his new book, A Series of Glances

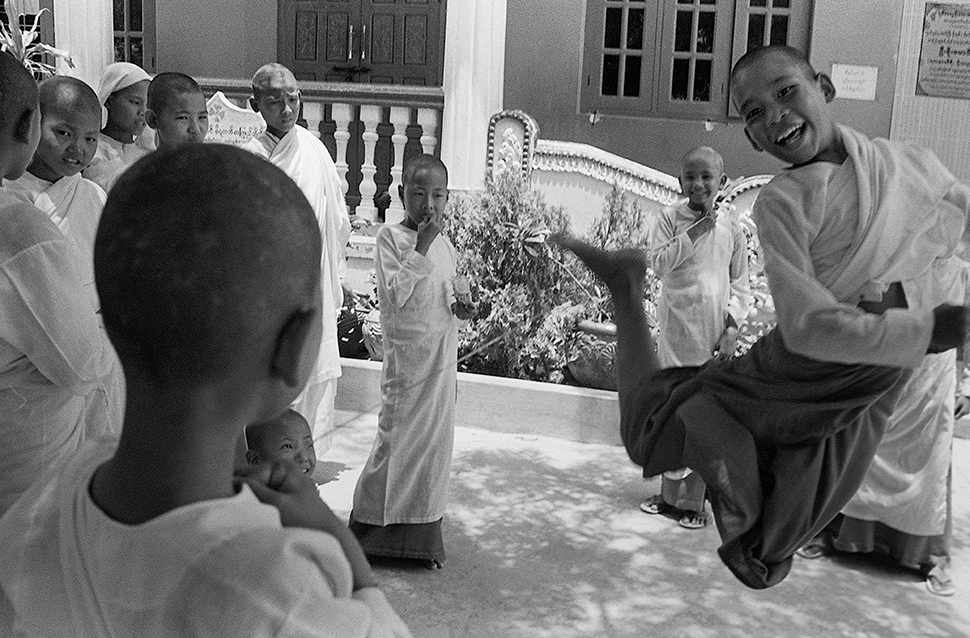

Andy Summers isn’t the first successful musician to have reached for a camera, but he can certainly play it as well as a six-stringed instrument. A fêted guitarist, known for his distinctive and inventive output for The Police and subsequently as a solo artist, Summers’ photography is no less interesting and accomplished. Leafing through his latest photo book, A Series of Glances, a lot of the photographs exhibit a cinematic quality, and have graced many a gallery wall over the years.

Keen to discover more about Summers’ influences and his photographic journey, we spoke to him over Zoom from New York.

What led to the publication of A Series of Glances – is it a ‘where we are now’ study?

I wouldn’t say it’s a ‘greatest hits’, but it is a survey of my involvement in photography since I started in about 1980. That’s what it is. I think it’s probably the best book I’ve done so far, and I’m pretty pleased with it. It is almost like a career retrospective, I guess, but it’s not the end – I’m working on another book already, with another publisher in England, and the subject matter is very different.

Are there many things that you still want to document in your photography?

Yes. I’ve been a bit restricted in the last three years, obviously, because of the pandemic; but I’m a traveling guy, so I always go fully loaded with Leica cameras to shoot photos wherever I am. Maybe I get something, maybe I don’t. I have got a lot of live shows coming up between now and mid-December so, you know, there’s a little part of me that’s thrilled I’ll be able to go out there and create some new photography.

I’m also pleased that A Series of Glances has a retrospective look to it, showing various countries and places I’ve been. It took me a while to put it together, but the next book I’m doing will be much more specific in terms of its material.

In the book, you praise your Leica M for being able to be played like one of your guitars...

It’s a fancy way of putting it, I suppose, but I don’t think it’s so far-fetched – I’m someone who has spent his life with two hands on something with strings on it, and have usually made it work. The big breakthrough for me actually came from the great Ralph Gibson, with whom I became strong pals in the early 1980s. I was using a Nikon, a clunker, and he said that I should try a Leica – he was obviously a Leica guy.

So I went and bought a Leica at B&H Photo in New York. I immediately got the tactility and the size. It was a beautiful thing and, for me, having been a tactile person all my life, suddenly I felt that the Leica was the right camera. Like certain guitars, it fits your hands, your body and all the rest of it, so as well as the mental side there is a physicality to it.

For me, as a physical object, the Leica handles much better than any of these big things with long lenses. You’ve got something that’s a part of your body, and it just feels like I can navigate through the world better with this type of smaller camera than any big thing.

Which Leica cameras have you used?

I’ve been through many, obviously. I started off with an M42 film camera, then an M5 and an M6. In 2012, Leica came out with their first digital, the M7. I jumped straight on it. I had just done almost a month traveling all over Asia, shooting film. I was carrying a bag of 90 rolls of exposed film and I was getting so paranoid about getting these things through the airports. That was the moment I switched. You can romanticize about film and wish you were still shooting on emulsion and all that, but I’m into digital now and happy with it.

I think digital actually helped me become a better photographer in many ways because I could judge better. In the old days, we would probably give it a couple more f-stops and do all the normal stuff. Having the picture on the back doesn’t make you lazy, because you’ve still got to make all the judgment calls – whether you want a deep focus or a shallow depth of field, do you use a 28mm lens or stick to a 50mm?

All these things became much more apparent on the back of the camera and you learn to hone your skills, rather than just hoping that you’re getting the photo, as you would have done before digital.

What is your typical setup for shooting?

For my normal practice, I have a black-and-white Leica M10 Monochrom and I’m starting to shoot some color now, more than before. I used to go out with one body and one 50mm lens, and wouldn’t even think about anything else, but now I usually use a 28mm, a 50mm and maybe a 90mm.

I used to use a 35mm all the time but stopped doing that, except that I recently acquired a new Leica lens that goes to f/1.4. It’s a limited edition of a 1960 lens that they brought out; I got one and have been playing around with that, and it’s great because you can shoot at night. I also have the small 1970 Noctilux lens, which is a beauty that’s close to f/1.2, so you get incredible bokeh and breakout of the imagery behind the central subject.

So yes, I’m a Leica man, and I’m extremely happy with that. There’s nothing else like them; you can’t compare any other cameras to a Leica. It’s a particular mental mode and a way of seeing and thinking.

When you visit a new location, what do you consider good subjects to be for taking photos?

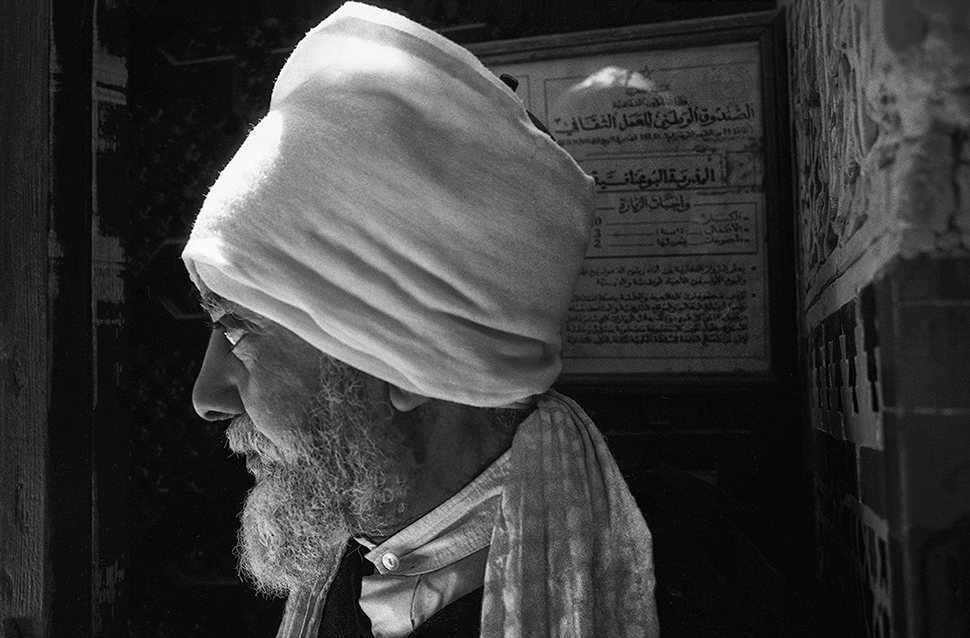

There are many ways to think about that, actually. I’ve been to places like Tibet, Nepal and western China and when you think about something that sums up the atmosphere, the vibe and the culture, those can become more corny pictures. Why are you taking a picture of this idol over here? I’m shooting a leaf that’s got sunlight on it or something more abstract.

Trying to sum up the culture in three or four photographs is not really my bag; I’m looking for more formal abstractional surrealism or something. Sometimes it works. I don’t do what you just mentioned because that’s just a kind of superior holiday snap, and I don’t really want to do that.

When you take photos, are you taking them for yourself or are you thinking of the wider audience?

As someone who has made records all his life and is used to the idea of always living with a permanent audience, you think you’re famous and you think you’re somebody. You’re not, of course, but you think you are, and you think there are people watching everything you do. Most of my life I’ve existed with this idea that some people are watching you to see what you’re going to do next, and that’s exciting.

But I’m not halfway up a mountain in Nepal thinking that the audience is watching me. ‘Am I going to get a shot here before my fingers fall off?’ When you’re back at home sorting out all the photos you’ve taken, that’s when you start to put it all together – there’s the wildness of the moment and then there’s the calm, collected bit later. So I think you work with more than one mindset.

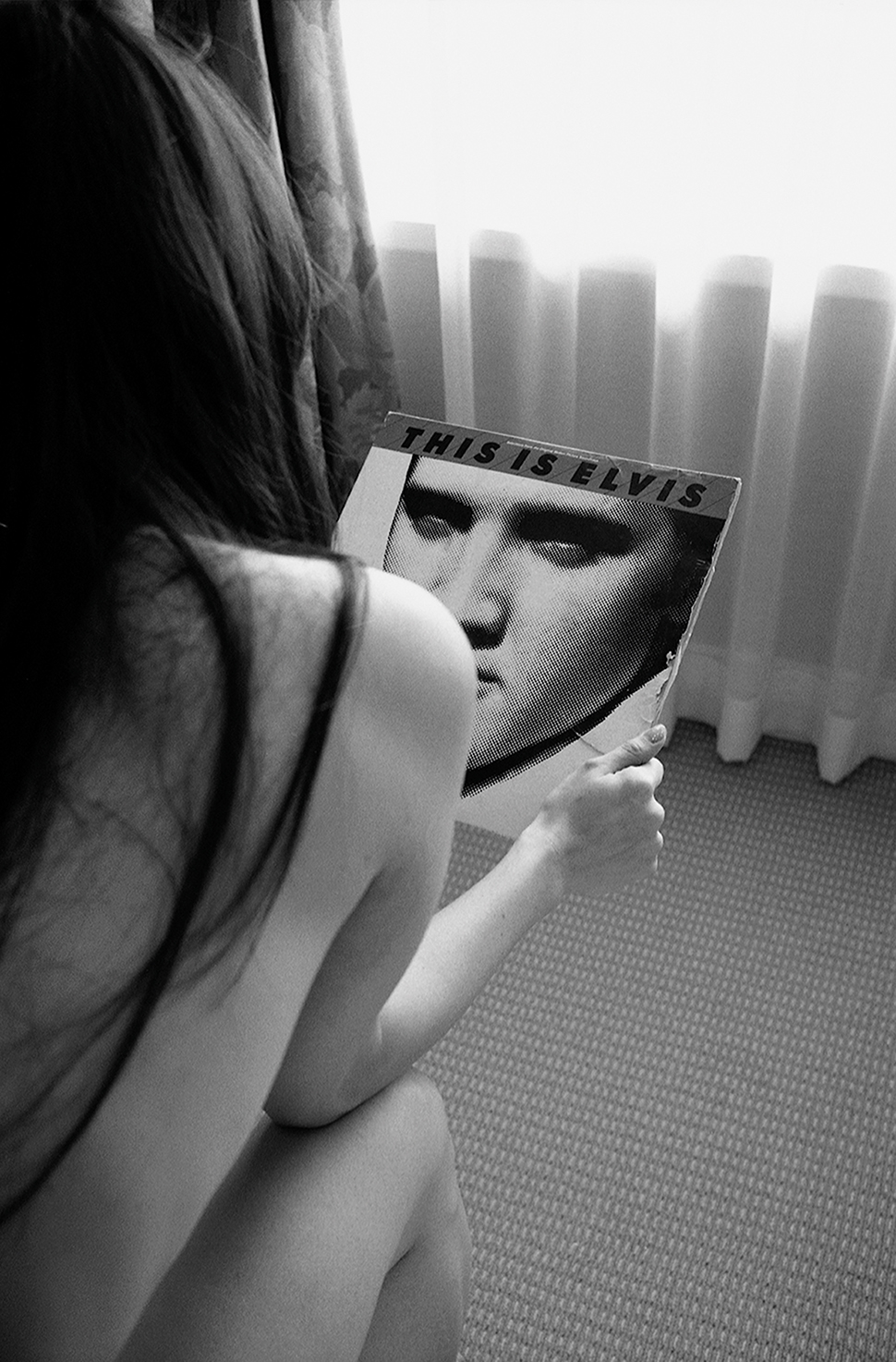

In A Series of Glances, you mention your love of arthouse films – and you can really see this influence in some of your photos.

I honestly think it’s really where it came from for me because I was just a kid in an English town and there was a cinema, the Continental, and that’s what they showed. I saw films by Fellini, Bergman, Godard – all that kind of thing – and was absolutely beguiled by it all. I was a real fan of those films; I didn’t necessarily understand them all but it opened up the world to me at a young age. So in terms of my formative years, it was very important – that’s where my love of photography came from.

But you were more drawn to American photographers than European ones. Why was that?

As I progressed on the guitar as a kid, I was really drawn to American jazz guitar players, along with Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. I was copying it all, and trying to understand the chord changes was pretty intellectual. I was taking in a lot of American stuff and, of course, it turned out that there were lots of great photographers in America that you wanted to be like – Garry Winogrand, Ralph Gibson, Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander, for example. When I got into photography, I was like, OK, I’m really going to do this.

How would you describe your photographic style?

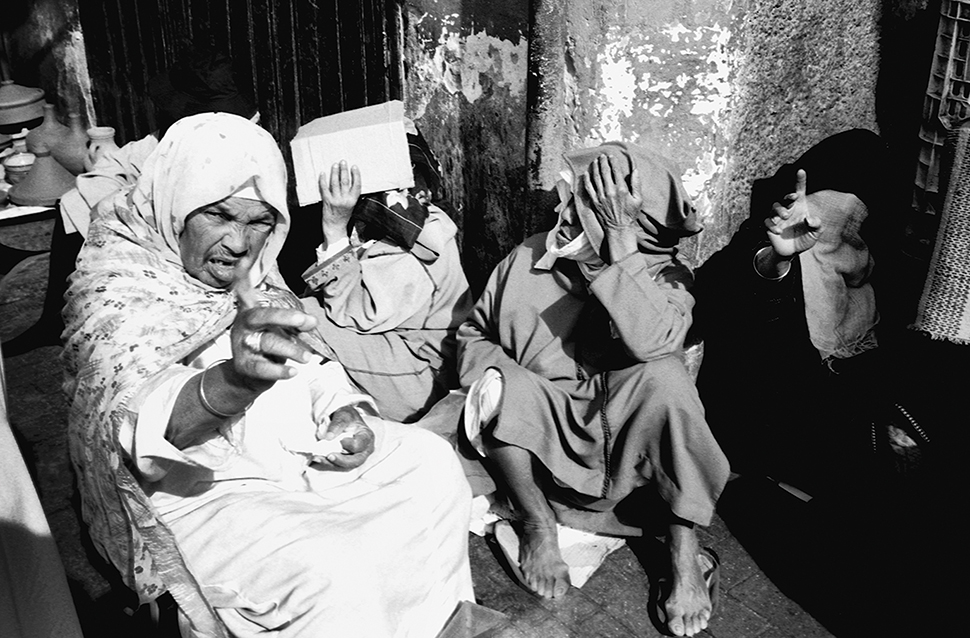

It’s just like music. It’s a great parallel. You start to improve your eye and you see the power of abstraction, and then you start to get into more than just, ‘Oh that mother crying with her baby is a nice emotional moment’. You start to get more into form, line, shape and position within the rectangle, and that’s really the point you have to get to.

I think photography at a certain level becomes formal and I like that because, for me, then it became more the equivalent of music. I’m not trying to just shoot emotional pictures like someone would do for Life magazine, but pure photography instead. Like pure music, pure photography.

Which images or sequences of images are you particularly proud of in the book?

I have tried to balance it out so that there are emotionally challenging pictures and some that just have formal qualities. It’s like having a meal where there’s some astringency in some of the tastes and you think, ‘Mmm, what’s that you’ve combined in there?’

There’s some obvious stuff, like the people in Nepal; some of them resonate just because they’re in foreign places. There are men on the banks of the River Ganges and other places, as I was passing through India at some point. The girl in China reaching up, which I used for an album cover… they’re all pictures that I like, and I can associate memory with all of them. It’s funny to say, but there’s a lot of happiness in this book because I remember all these events and what I was doing or going through at the time.

Did it take long to sequence the book’s photos?

About six months, and I was doing some shows at the same time. The model for A Series of Glances was The Lines of My Hand by Robert Frank, one of my favourite photographers. I used it as the model for the layout – a vertical here, two horizontals, a full spread and so on. I really liked Frank’s book in terms of its rhythm.

Do you ever shoot photos on a smartphone?

Like everyone in the world, I do carry one. But it’s rare that I would actually use it to take photos.

They do get better and better every year, though…

Yes, but I’m going to keep using my Leica. I love the aesthetic [in the photos] – you just get something different. Leica works for me, and I’ve never felt any need to turn away from it. Three years ago, Leica made a signature camera for me; Fender had done a special guitar for me covered in photographs, and Leica did the same with a Leica M. That was a good moment.

A Series of Glances by Andy Summers is published by teNeues and is priced at £75/$110.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Niall is the editor of Digital Camera Magazine, and has been shooting on interchangeable lens cameras for over 20 years, and on various point-and-shoot models for years before that.

Working alongside professional photographers for many years as a jobbing journalist gave Niall the curiosity to also start working on the other side of the lens. These days his favored shooting subjects include wildlife, travel and street photography, and he also enjoys dabbling with studio still life.

On the site you will see him writing photographer profiles, asking questions for Q&As and interviews, reporting on the latest and most noteworthy photography competitions, and sharing his knowledge on website building.