Kodak Instamatic: a brief history of the best-selling camera that shot the swinging sixties

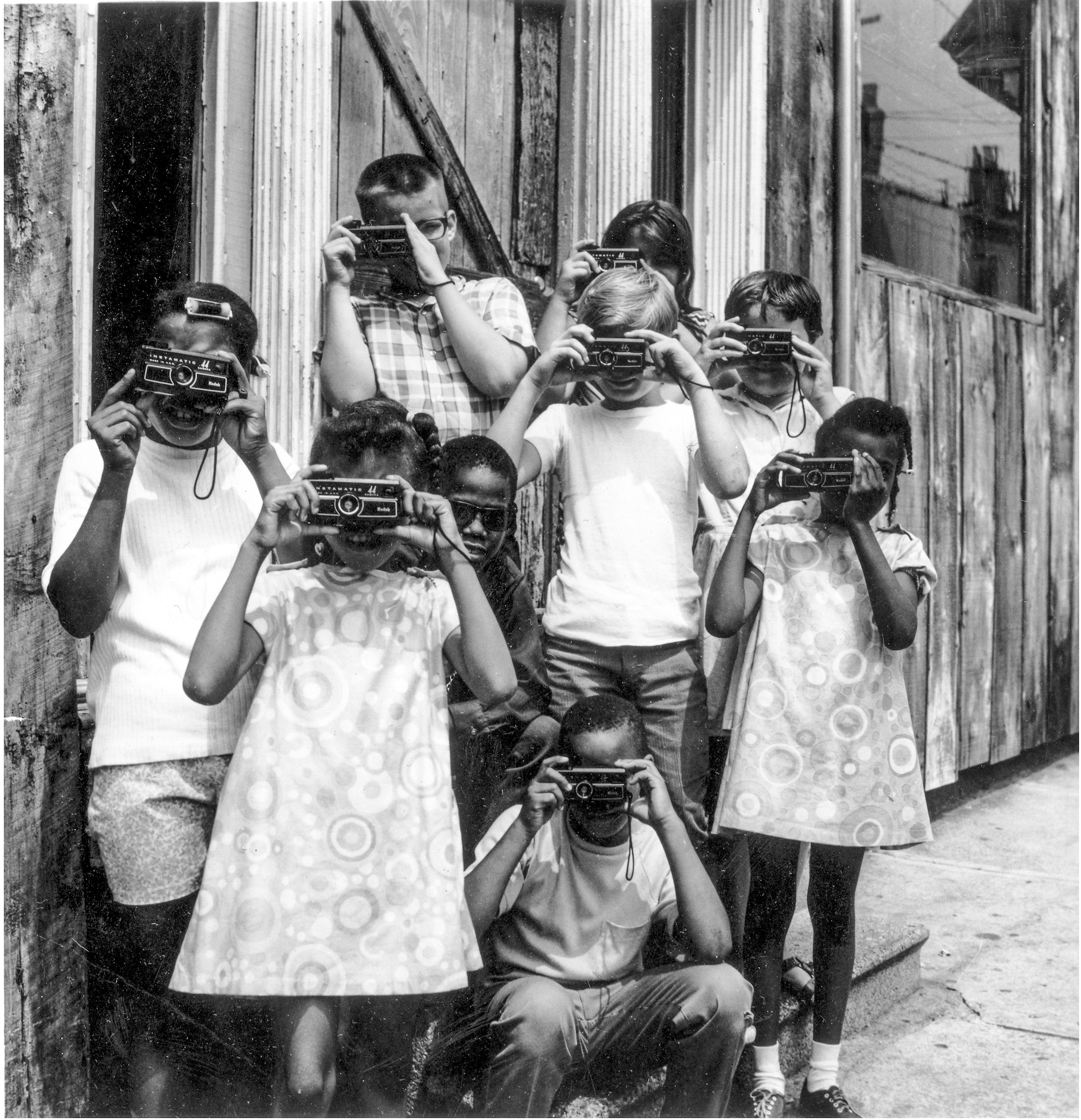

Introduced in 1963, over 70 million Kodak Instamatic cameras were sold by the start of the 1970s and became part of a great many people’s lives

If you were born in the Sixties or grew up in that decade, there’s a very good chance that the key milestones in your early life were documented by an Instamatic camera… most likely badged Kodak, but possibly also from Hanimex, Halina, Ricoh, Agfa and Minolta among quite a few others.

Kodak made its name – and, for many decades, its millions – devising cameras to bring photography to the masses. It was the lifelong obsession of the company’s founder, George Eastman, and it all began in 1888 with the original ‘Kodak’ box camera. This was more a complete system than just a camera, and the idea was that users never had to handle the film.

Ultimately, though, sending the whole camera back to Kodak for processing, printing and reloading was never going to be viable in the long term. Moving from roll film to a cassette-based system was a step in the right direction, but there was still a lot of room for error and mistakes meant memories lost forever.

In the early Fifties, Kodak initiated “Project 13” to design a camera that was completely foolproof in every area of its operation, and totally reliable – not to mention very affordable. Like the original Kodak, it was based on the idea of an integrated camera and film system. The film was 35mm wide, but with a backing paper, and housed in a plastic cartridge that incorporated both the feed and take-up spools.

It was designed so that it could be easily drop-loaded into the camera and, importantly, there was only one way to do this. The camera’s transport system only required one sprocket per frame, so the negative size was 28 x 28mm, and the wind-on knob or lever only needed a short travel. The square format meant that the camera didn’t ever need to be turned on its side. The actual image area of 26.5mm square gave rise to the film’s designation of ‘126’.

Extensive use of plastics, both for the ‘Kodapak’ film cartridges and for the camera bodies, enabled mass production, which greatly reduced the manufacturing costs. Because the lenses, made from a single high-quality acrylic element, had a short focal length and a small aperture (43mm f/11 on the cheapest models), they delivered quite sharp results. The camera was named the ‘Instamatic’ by Kodak – derived from instant (as in the film loading) and automatic – but it eventually became the generic term for any camera in the 126 format.

The system was subsequently licensed to numerous other manufacturers and, because the Instamatic system enabled care-free snap-shooting, film consumption increased dramatically – so much so that, initially, film processors had difficulty handling the volume of Kodapak cartridges. This led to a revolution in photofinishing after a means of a high-volume processing was devised, by splicing together the film lengths and employing the same continuous developing process that was being used for motion picture film.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Initially, Kodak 126 film was available in black-and-white (ISO 125 Verichrome Pan), color transparency (Kodachrome 64 and Ektachrome 64) and a new generation color negative emulsion called Kodacolor-X, which was initially rated at ISO64 and then ISO80. Kodacolor II arrived in 1972, rated at ISO100. There was a choice of 12- or 20-exposure lengths, the latter later replaced by 24 frames. Notches on the cartridge relayed the film speed to the Instamatic cameras that had built-in metering, otherwise the wide exposure latitude of Kodacolor-X ensured a decent print from most lighting conditions.

Agfa, Fujifilm, Konica and Ilford also made 126 films, and these products were repackaged by a great many other brands including Soulcolor and Pacific Film in Australia.

• A history of Kodak: from underdog to household name

There were numerous Kodak Instamatic models and, outside the USA, the cameras were also built in a number of other countries including Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany and Australia. Instamatics were mostly assembled in Australia (although some parts were made locally) and these models were stamped ‘Kodak (Australasia) Pty Ltd’ inside the camera back (although the first examples apparently carried a sticker indicating the country of origin).

While the 126 format was primarily devised to make life easier for the snap-shooter, Kodak – along with Rollei, Ricoh and Zeiss Icon – did introduce more advanced SLR models. Made in Germany, Kodak’s Instamatic Reflex was available from 1968-74, and as an aside was one of the very first SLRs with an electronically-controlled shutter. There was a choice of Schneider-Kreuznach interchangeable lenses, using the Retina mount, from 28mm to 200mm.

Kodak continued building Instamatic cameras until 1977, but by now the emphasis was on the smaller 110 format that was called the ‘Pocket Instamatic’ range. Production of 126 film by Kodak ceased in 1999, but the Italian company Ferrania kept making it until 2008 (branded as Solaris).

In terms of introducing legions of new people to photography, no other camera or format has been so successful in such a short time as the Kodak Instamatic.

Take a look at the best film cameras available today, along with the best film for 35mm cameras. If you love the classic look but want contemporary technology, check out the best retro cameras.

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.