Like it or not, DSLR users, your next camera will almost certainly be mirrorless

With the development of new DSLRs now all but at an end, enthusiasts are being forced to go mirrorless. Here’s everything you need to know about making the big switchover.

If you’re still shooting with a DSLR – and thousands upon thousands of photographers are – then it’s very likely that you’re completely happy with it, and don’t particularly want to be forced into making a change. Snag is, the DSLR’s days are basically done as just about all the mainstream camera makers pour all their resources into their mirrorless systems.

While there are new mirrorless cameras arriving all the time, there’s only been one or two DSLRs in the last couple two years… and they are basically upgrades of existing models.

The DSLR’s days are basically done as just about all the mainstream camera makers pour their resources into their mirrorless systems

As often happens with new technologies, the development can be well ahead of the market and that’s exactly what’s happening here… there are still a great many photographers using DSLRs, but they’re rapidly running out of options in terms of upgrading or replacing their existing cameras. Models are steadily being discontinued, as are lenses and accessories so, like it or not, DSLR users are increasingly having their hands forced when it comes to buying their next interchangeable lens camera.

On the plus side, there are many good reasons why the interchangeable lens camera makers are backing mirrorless and we’ll look at all of these shortly, but there is still possible to buy a new DSLR, at the moment, should you be inextricably wedded to the reflex mirror and the optical viewfinder. That said, most of these models are at least five years old (and many are much longer in the tooth), so you’ll be buying simply to get something newer than what you’ve got now rather than something that will give you increased capabilities and better performance.

The reality is that, sooner or later for most current DSLR users, it’s going to be crunch time, so it’s important to know what’s involved and what are all the options.

Views On The Finder

Probably the two biggest issues to contend with when making the switch from a DSLR to a mirrorless camera are the viewfinder and the lenses. Yes, both of these are real biggies, so it’s no surprise that you might be apprehensive or reluctant to give up something you know and love, and make a jump into the unknown.

The mirrorless concept has been around for a very long time in the shape of the rangefinder camera, and it was Leica in particular who took advantage of the configuration to design its superlative M-mount lenses. Without a reflex mirror and its mechanism to accommodate, the distance between the lens mount and the focal plane (the point at which a lens is focused) is much shorter, which has lots of advantages when it comes to designing lenses.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

A shorter back focus distance – also called the flange distance – makes it easier to achieve more uniform center-to corner sharpness, and there is also greater flexibility with what can be done with a lens’ optical design, especially for wide-angles which, incidentally, was always the big strength of the rangefinder camera systems over those for SLRs.

Of course, the rangefinder cameras had (and still have) optical viewfinders, but these are a non-TTL design and it limited the use of telephoto lenses to about 100mm in focal length (with the 35mm format), which is why the reflex camera with its TTL-type optical finder ultimately became a lot more popular. With the digital mirrorless camera, it’s possible to have everything, which is primarily what’s been driving the development of this configuration.

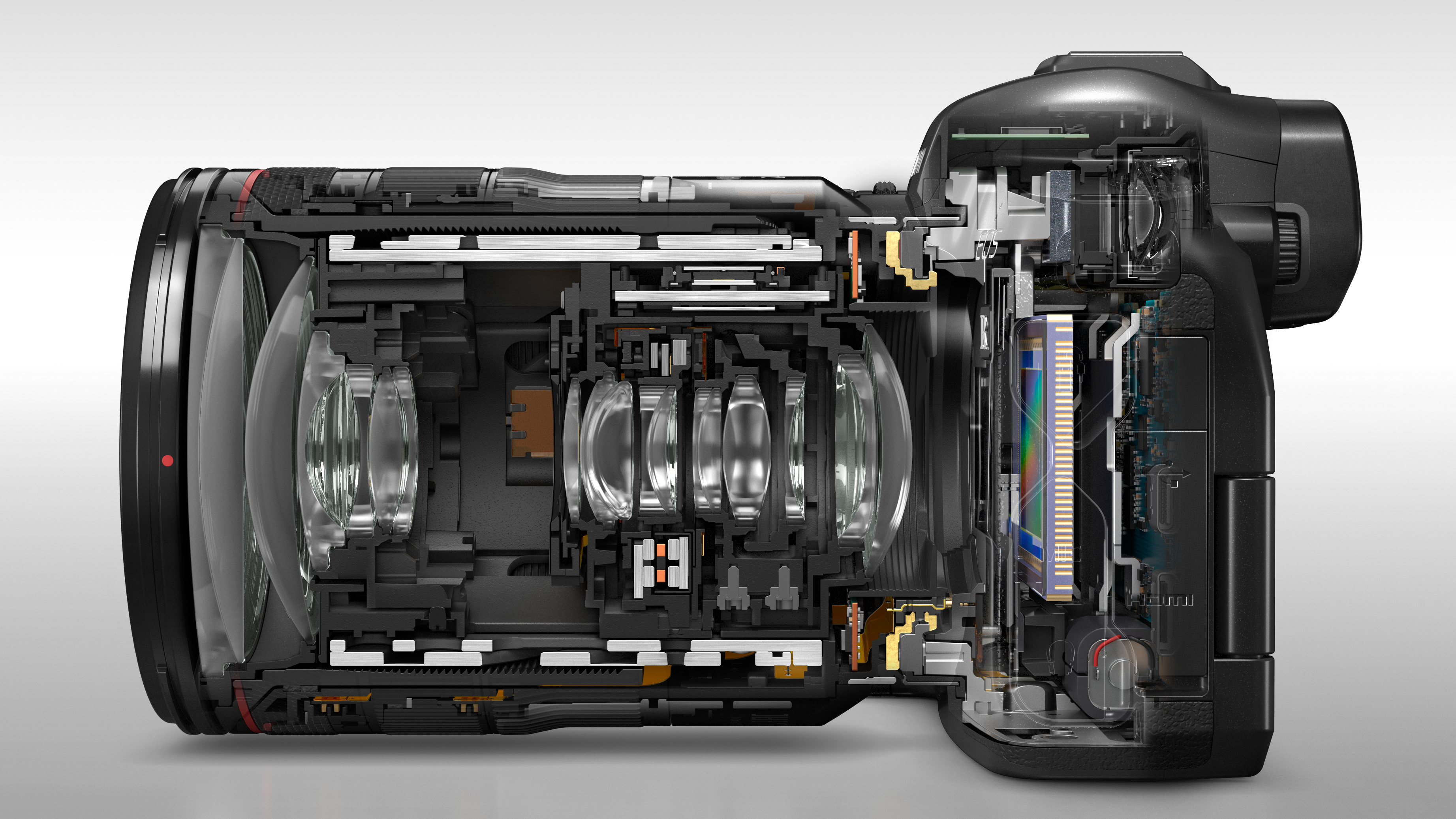

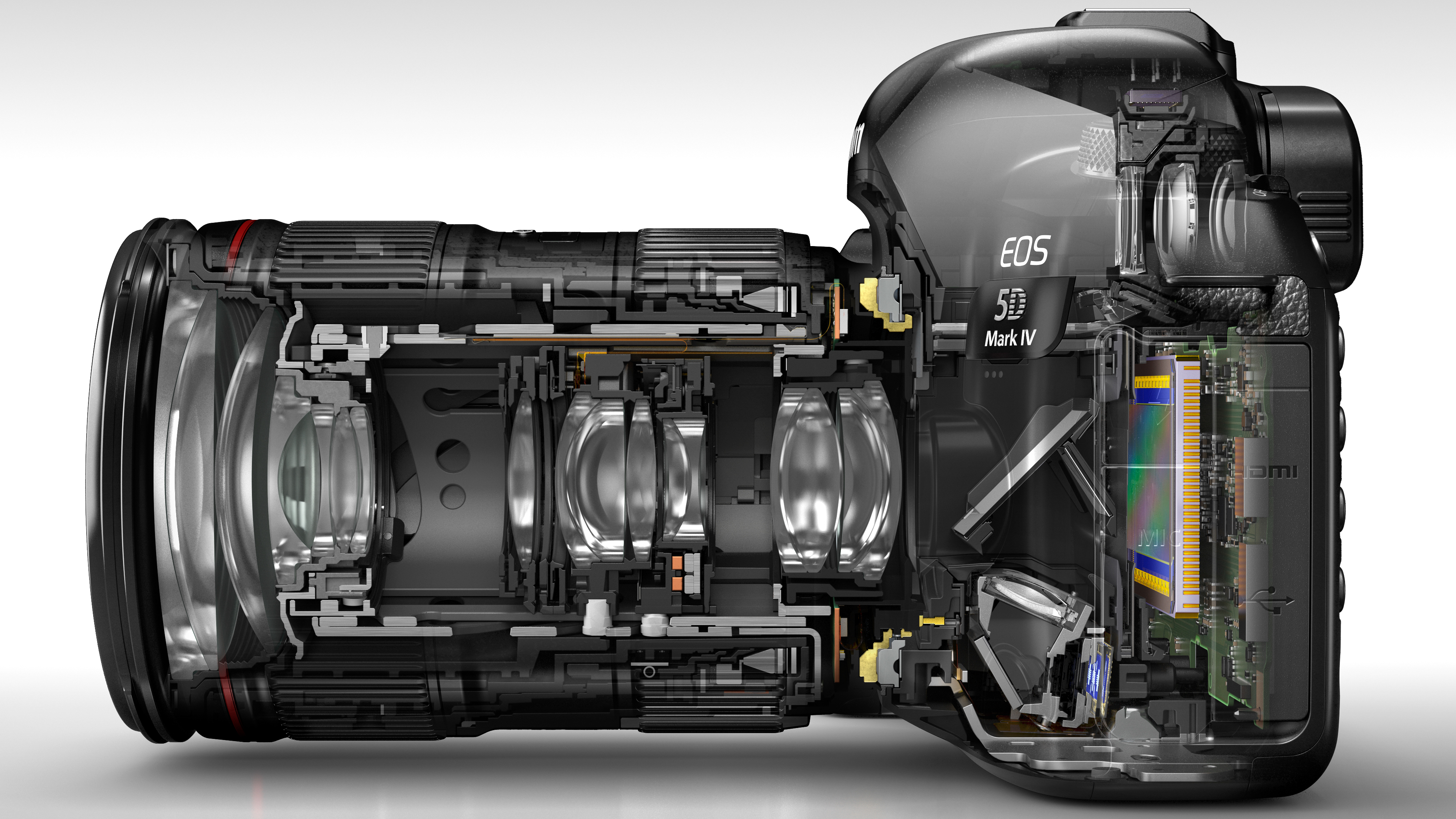

The big breakthrough has been the refining of the electronic viewfinder (EVF) to the point where it delivered acceptable color, contrast, resolution, dynamic range and refresh rates. Think of the EVF as a mini flat panel TV that gets a live feed directly from the imaging sensor. Not only does this eliminate all the bulky componentry of the reflex camera’s mirror box and optical viewfinder – which is either a pentaprism or penta-mirror arrangement – it allows every camera setting to be previewed, especially useful when you’re applying special effects or filters.

Also eliminated are the noise and vibrations created by the reflex mirror’s operation and the limits this places on continuous shooting speeds. Current pro-level DSLRs can shoot at up to 12fps with the reflex mirror, and going any faster requires the mirror to be locked-up, at which point they’re essentially operating as a mirrorless camera anyway. The higher-end mirrorless models can now shoot at 20fps, or even 30fps, when using the electronic shutter instead of the mechanical shutter (which is again limited by the mechanical operation of its blades).

Dedicated DSLR users still point to the OVF as one of the reasons for sticking with the reflex camera, and while it’s true that the optical viewfinder is still superior – as Canon described it when the EOS-1D X Mark III was launched, it “ensures you are connected to your subject in real time with zero lag” – the latest generation EVFs are hard to fault. It’s a different experience, of course, but one that you will get used to very quickly.

New Lenses… Or Old

The lens question is perhaps even thornier for DSLR users thinking about switching to a mirrorless system. Note the word “system” because we’re talking about both camera bodies and lenses here. The mirrorless configuration demands a new lens mount, which – in 35mm SLR history – was always done very reluctantly by the camera makers as it caused so many issues for users of the old mount.

Canon gritted its teeth when switching from FD to EF in order to enable a more efficient autofocus system, while Nikon tried to make its existing F-mount work in a bid to maintain compatibility, but encountered restrictions down the track and eventually ended up changing everything but the physical fitting.

The saving grace this time around is the availability of adapters to help ease the financial pain that’s always associated with switching lens mounts. These adapters essentially reset the flange distance back to that of the SLR system, so the latter’s lenses can be used without any loss of capabilities (i.e. AE and AF functionality) or optical performance.

It is, nonetheless, still a compromise as you’re missing out on the various benefits that the mirrorless camera configuration brings to lenses – among them even better optical performance, enhanced in-camera corrections, and the potential for more compact designs with faster maximum apertures. Once again, sooner or later, you will have to consider adopting dedicated mirrorless system lenses, but at least it’s possible to use a mirrorless body with all your SLR lenses so you can contemplate making the switch step-by-step.

With some more specialized lenses – such as expensive fast telephotos, for example – you may well simply opt to go on using them with an adaptor because there’s virtually nothing to lose functionality-wise, but potentially quite a bit to lose financially with a changeover (assuming there is a mirrorless equivalent available).

Staying Brand Loyal… Or Not?

The big question that Canon and Nikon have been sweating on is whether its DSLR users will stick with them when they make the transition to a mirrorless camera. It’s a valid concern because, if you have to change lens mounts anyway, then why not consider everything that’s out there?

The risk of defections has been greatly reduced now that both Canon and Nikon have rapidly expanded their full-frame mirrorless camera systems – making for a smoother switch on many levels – but there is credible competition from Sony, Leica and Panasonic or, if you’re contemplating a cropped sensor system, also Fujifilm and Olympus.

For the record, Canon, Nikon and Sony also offer mirrorless systems based on the APS-C sensor size, while Panasonic pioneered the Micro Four Thirds format. The world’s very first mirrorless digital ILC was the Panasonic Lumix G1 (which my colleague James Artaius recently took a fresh look at) unveiled at the 2008 Photokina.

In the full-frame sensor size, Sony launched its FE-mount system in October 2013 and has subsequently built it into a range that currently comprises nine camera bodies and over 70 lenses. It has also pioneered a number of new technologies especially in sensor design, and makes the most compact conventionally styled full-frame camera bodies.

The lens system covers everything from ultra wide to supertelephoto and all points in between (plus the mount is well supported by third party lens makers), so Sony is the most logical place to look if you’re thinking of jumping ship from a full-frame Canon or Nikon DSLR. Mount adapters are available – something Sony actively encouraged in the earlier days, so it’s still possible to maintain full functionality – which means that you’re not entirely committed to swapping all your existing lenses.

Long term, though, there may be more of an imperative to adopt Sony optics and, of course, in the meantime you will have to learn a whole new camera layout and operation. Nevertheless, both Canon and Nikon are still playing catch-up with their full-frame mirrorless lens systems (although certainly all the ‘staples’ are now there) and the choice of camera bodies, so you might well be convinced to look elsewhere.

Panasonic’s Lumix S full-frame mirrorless system arrived at the same time as those from Canon and Nikon, but was immediately ahead in the lens race by virtue of using Leica’s L mount in a collaboration that also involves Sigma. Subsequently, there are already over 50 L-mount lenses from the three brands along with, currently, four bodies from Panasonic, and two each from Leica and Sigma.

Thinking Bigger… Or Smaller

If you currently use an APS-C format DSLR then there’s the option to move up to the bigger, full-frame sensor when you make the switch to a mirrorless camera, but this will more likely require you to replace all your lenses as well. The adapter route is still open as all the full-frame mirrorless cameras can be switched to the APS-C format when these lenses are fitted, but you will be using less resolution than is available, which seems like an unnecessary performance compromise.

What about dropping down a sensor size… from full frame to APS-C or even to Micro Four Thirds (MFT)? Believe it or not, there a few good reasons for considering this route. Firstly, the Fujifilm X mount, Sony E mount, and both the Micro Four Thirds lens systems are extensive, and there’s also plenty of choice from third-party lens makers too. Secondly, the smaller sensor size allows for more compact camera bodies and lenses, the latter further enhanced by the crop factors involved… 1.5x for Fujifilm X and Sony E, and 1.97x for MFT.

This means longer telephotos in particular can be made much smaller, lighter and more affordable. If you’re getting to a stage in life where the idea of lugging around a heavy bag of camera gear is becoming less appealing or you simply prefer to travel light without compromising your shooting capabilities, then the crop sensor mirrorless cameras have obvious appeal. Alternatively, mount adapters allow you to still use existing full-frame/35mm format lenses, which will also get a bump up in their effective focal length.

All of these manufacturers offer excellent enthusiast-level and pro-grade mirrorless camera bodies, which serves as a reminder that sensor size really doesn’t make any difference in a great many shooting situations. However, it’s not entirely a free lunch; at a given resolution, the smaller sensors will have smaller pixels, which means they have a lower signal-to-noise ratio.

This chiefly manifests itself as increased noise at higher ISO settings, so the higher sensitivity range is limited compared to a full-frame sensor with a similar resolution. More advanced noise reduction algorithms continue to deliver improvements in the high ISO performance of the smaller sensors, but ultimately there’s no getting away from the physics of a bigger photodiode with its increased sensitivity.

If you’re considering a complete switch of camera system, then what about medium format? Digital medium format photography was really out of reach of most non professional photographers (and, in reality, many professionals too), but the mirrorless configuration has made it more accessible and affordable.

We’re mostly talking about Fujifilm’s G-mount cameras here, but the Hasselblad X2D 100C is also comparably more affordable the now-discontinued H-system DSLRs. Fujifilm’s GFX series medium format cameras – which use a sensor sized at 44x33mm, 1.7x larger than full frame – are still at the more expensive end of the market, but there are already a good number of full-frame models in the same price bracket.

The GFX cameras – even the 102MP models – essentially share all the same functionality as the higher-end X-mount bodies, so they’re a whole lot more flexible than has ever previously been the case with medium format. The big question to ask here is whether you really need 50 or 100MP, or is your money better spent on a couple of new lenses to go with a less expensive camera?

Learning a new camera can take a bit of time, but you won’t really encounter anything dramatically different when switching from a DSLR to a mirrorless body. In fact, quite a number of mirrorless cameras are actually more traditional in their control layouts than most DSLRs – notably the higher-end Fujifilm X-mount bodies, Panasonic’s Lumix S line-up, OM-D, and Nikon Z mount. In reality, everybody has stuck with fairly conservative external designs – probably deliberately – so you won’t be in for any big shocks and everything is going to look pretty familiar, even though it’s a very different story on the inside.

The main camera systems – AF, AE and white balance – are unchanged in operation, but all function off the imaging sensor in a mirrorless camera rather than using separate measurement devices. In practice, you really won’t notice much of a difference except that the autofocus systems have a much wider frame coverage that enhances subject tracking capabilities. Additionally, sensor-based AF allows for more advanced object recognition using AI technology to precisely identify the type of subject to enable much more reliable tracking. And there’s scope for a lot more development to come.

As noted earlier, the electronic viewfinder enables previewing of any or all applied settings and, in most mirrorless cameras, can also show all the same displays as the rear LCD, including useful elements such as a real-time histogram, a highlight warning, and a level indicator. Additionally, most higher-end models also have a ‘touch pad’ facility that allows for the monitor’s touchscreen to still be used for selecting the AF point while you’re using the EVF. Enabling the EVF to replicate exposure settings enables you to see whether a shot will be under or overexposed or, perhaps more usefully, the effect of applying plus or minus exposure compensation. Yes, DSLR optical viewfinders are brilliant, but it doesn’t take long to become accustomed to using an EVF and making full use of all the extra information it can convey to you.

If you shoot video then switching to a mirrorless camera from a DSLR is really a no-brainer. A DSLR can only shoot video with its reflex mirror locked-up, in which case it’s technically operating as a mirrorless camera anyway. And with the exception of Canon’s EOS-1D X Mark III, no DSLR operates as capably in live view as a mirrorless camera, especially in terms of autofocusing.

Take It Slowly

On balance, the pros do outweigh the cons of making the switch from a DSLR to a mirrorless ILC, but that’s probably not going to make it any easier for anybody who really loves their reflex camera system and doesn’t want to change. As we said earlier, you don’t have to do it right now, but you’re only putting off the inevitable, and it really is better to get started on your mirrorless journey sooner than later. No matter what you decide about brand or format, the transition can be as fast or slow as you like.

A camera body and a mount adaptor will get you started, although it’s probably advisable to invest in at least one dedicated mirrorless lens (ideally close to whatever you’ve been using the most with your DSLR) and then slowly build a system as needed or finances allow. However, there is no truly compelling reason why you can’t go on using your favourite DSLR system lenses for as long as you like.

The key advice is to do your homework thoroughly and look at all the possible options in the light of what you need and use regularly, but also in terms what you might want to do in the future.

Mirrorless camera systems provide much more scope for the latter. It’s just a case of taking the first step and, as many parents often tell reluctant children, “You’ll like it when you get there”.

While the DSLR vs mirrorless cameras debate rages on, take a look at the best DSLRs and the best mirrorless cameras on the market today.

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.