Mayne Attraction: gritty portraits of life on the streets of 50's and 60's Britain

Roger Mayne is best known for his landmark documentary images of London's Southam Street. But as an exhibition at The Photographers' Gallery reveals, he was also a forward-thinking artist who pushed the boundaries of the medium

As a young photographer, Roger Mayne visited the slums of north Kensington 27 times, taking 1,400 photographs. It was in 1956 that he first came across Southam Street in north Kensington, some two years after he had moved to London. It was a slum, mostly demolished in 1969, but Mayne was enthralled by the unrestrained way that its residents lived and behaved. He took 64 photographs on his first day alone.

“He was forward-thinking in terms of the lack of a national collection for photography,” says Karen McQuaid, the curator of the Roger Mayne exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. “He was very persistent in his campaigning for a wider appreciation of photography and an acknowledgement that this was the medium, bar the printed word, that was about to be the most influential.”

Although he avoided directly political statements, he was drawn to photographing poorer working-class communities, a fascination most famously expressed in his north Kensington work. “I think an artist must work intuitively, and let his attitudes be reflected by the kinds of things he likes or finds pictorial,” he wrote. “Attitudes will be reflected because an artist is a kind of person who is deeply interested in people, and the forces that work in our society. This implies a humanist art, but not necessarily an interest in ‘politics’.” Mayne’s lifelong fascination with people – their moods, expressions, relationships and interactions, both with each other and their environment – permeates his work.

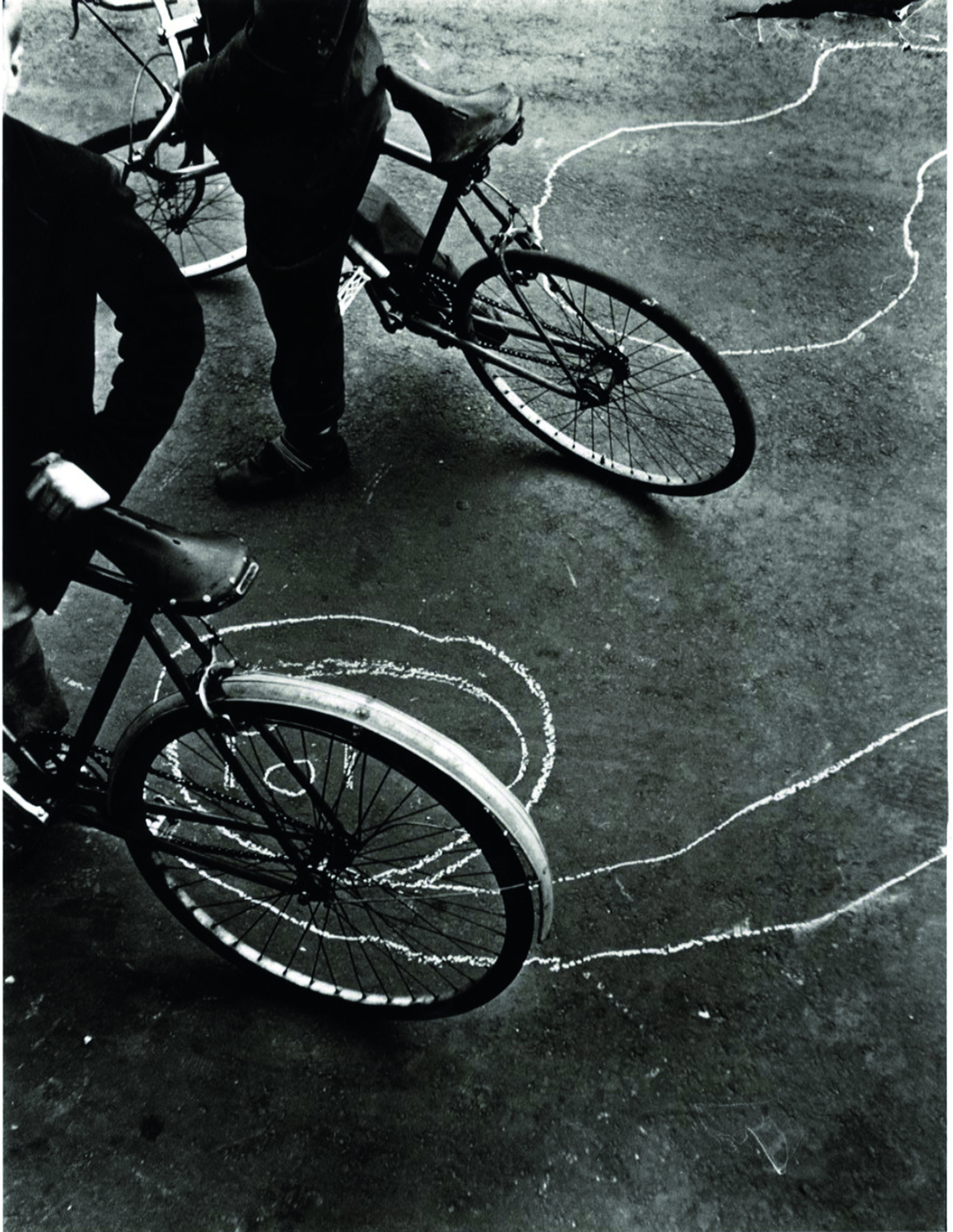

It’s easy to forget that his photographs of the ever-fascinating Southam Street were only part of a much wider body of work. The exhibition, curated by Karen McQuaid and Anna Douglas, in association with Mayne’s daughter, Katkin Tremayne, brings to the fore some of the other projects that the Southam Street work overshadows: bicycle factories in Nottingham to council estates in Bermondsey.

You’re struck by the consistently high quality of Mayne’s work and the way he continued to develop underlying themes such as changing youth culture, social housing and immigration. It smacks of Paul Strand, one of his biggest influences, but without the political edge: it explores his approach to photography as an art form through his willingness to experiment and innovate.

UNIQUE POWER

For Mayne, photography possessed unique qualities that could be exploited for creative expression. In 1960, he wrote: “Photography involves two main distortions – the simplification into black and white, and the seizing of an instant in time. It is this mixture of reality and unreality, and the photographer’s power to select, that makes it possible for photography to be an art. Whether it is good art depends on the power and the truth of the artist’s statement.”

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Mayne, born into a middle-class family in 1929, didn’t initially seem destined for a life in photography. After being privately educated at Rugby School, he studied chemistry at Balliol College, Oxford University. He didn’t enjoy it and in his spare time, inspired by Henri Cartier-Bresson and W Eugene Smith, he began taking photographs of his own. By his final year in 1951, he had his first images published in Picture Post – a photo-essay on a ballet film.

After university, he was expected to undertake two years’ national service, but his pacifist beliefs led him instead to work as a hospital porter in Leeds. While living there, he began shooting his earliest street images and developed his distinctive ‘realist’ style. By the time he held his first UK exhibition, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1956, he was freelancing for a range of magazines including Vogue, Queen, New Left Review and Peace News.

IN LOVE WITH THE STREETS

“The reason for photographing poor streets is that I love them,” Mayne wrote in 1959. “Empty, the streets have their own kind of beauty, a kind of decaying splendour and always great atmosphere – whether romantic on a hazy winter day, or listless when the summer is hot; sometimes it is forbidding; or it may be warm and friendly on a sunny spring weekend when the street is swarming with children playing, or adults walking through or standing gossiping.”

He gained the trust and acceptance of people in the street and captured people in the everyday dramas and quiet moments of their daily lives without either romanticising or patronising them. He used a pre-focused Zeiss Super Ikonta and often got such close proximity to his subjects that one feels immersed in their world.

Many of his photographs concentrate on the action-packed lives of the street’s children – playing football, fighting, smoking, giggling – against the contrasting backdrop of run-down houses. The buildings may be decaying and hazardous to health, but the streets are full of life. Mayne’s pictures record the changing youth culture and emerging groups of Teddy Boys as well as early signs of multiculturalism with the arrival of West Indian immigrants.

Karen McQuaid says that Mayne was able to get such an intimate insight into his subjects’ lives by himself becoming a regular feature of street life. “The people of Southam Street were very aware of his presence,” she says. “In his writing he talks about changes in behaviour because he is present, but he also goes on to say that if you’re present often enough, and if you wait for those few seconds more, then people’s guard is dropped. There’s a passage in his writing about watching a boy playing football and how he registered Mayne’s camera, but his attention span wasn’t long enough to stop him playing. Those spaces, and those he was drawn to, were so active and loud and boisterous that he became just one other layer of activity and was quite soon ignored.”

McQuaid believes that part of Mayne’s attraction to the area was its complete contrast to the middle-class household in which he had been raised. “He’d had a strict, Victorian, buttoned-up upbringing and his response to Southam Street was slightly jaw-on-the-floor,” she says. “He was used to a living situation where family life took place indoors, out of sight. Suddenly all of the life and activity, the screaming, shouting and playing, was being very publicly displayed. It was a huge, joyful shock for him.”

The Southam Street work, which Mayne pursued for five years, contains around 1,400 images. They were quickly recognised as making a significant body of work. One of the images was selected by the novelist Colin MacInnes as the cover of his 1959 book Absolute Beginners, then 57 of them were published in Theo Crosby’s design magazine Uppercase in 1961. A selection of the work was later published by the V&A as The Street Photographs of Roger Mayne (1986).

CAPTURING PEOPLE

“Mayne’s Southam Street work is a milestone within the history of British documentary,” says McQuaid. “But what I hadn’t appreciated until I spent some time in the Mayne archive, was just how substantial his other bodies of work were.”

The other work featured in the exhibition includes a 1964 documentary series made at Raleigh Cycles in Nottingham. Mayne initially took some pictures of the factory while working alongside a BBC documentary film-maker, but subsequently returned several times to develop the work further. Shot in the low light of the factory floor, these sensitive portraits highlight the dignity and diligence of the workers.

In another longer-term project, Mayne was commissioned to photograph Park Hill in Sheffield – a new council estate built to replace an area of back-to-back housing declared unfit for human habitation. The estate was completed in 1961 and Mayne photographed it numerous times over four years. For McQuaid, this is a unique body of work and one that has always been under-appreciated. “The built environment of Park Hill couldn’t have been more different from Southam Street, yet the photographs have the same energy and buoyancy,” she says. “Park Hill was still smelling of fresh paint and new concrete, but Mayne paid the same attention to the mini-dramas of the everyday and the physical engagement of people with each other, within these spaces. Choreography is an important aspect of Mayne’s work – people moving through the built environment – and he manages to turn that into something so elegant so often. It’s quite incredible for me that he essentially makes the same type of pictures in these two markedly contrasting environments.”

PERSONAL INFLUENCES

Mayne wasn’t restricted solely to the company of photographers, and was also friends with abstract painters from the St Ives school of artists including Patrick Heron, Roger Hilton and Terry Frost. This wider interest in the arts encouraged him to think of new ways of presenting photographic images, including large-scale prints and diptychs and triptychs, as well as installation work.

Mayne went on to work for the Observer and The Sunday Times colour magazines and taught at Bath Academy of Art from 1966 to 1969. In the 1970s, he moved to Lyme Regis in Dorset with his family. His work broadened to include landscapes, while still exploring the theme of childhood in photographs of his own children and later grandchildren. In the 1980s he shot street pictures in China, Japan and Goa, and in the nineties he was still out photographing street scenes in countries including France, Spain and Italy. He continued working until late in life and died in 2014 at the age of 85.

While Mayne’s documentary work in the fifties and sixties was his most significant contribution, McQuaid believes it’s the way that he engaged with the medium that set him apart from his contemporaries. “He was certainly ahead of his time in his thinking about how photography fitted into wider culture,” she says.

CREATIVE EXHIBITION

Perhaps the most surprising part of the exhibition is Mayne’s innovative installation The British at Leisure, which is being shown for the first time since it first went on show in 1964. McQuaid says that finding the material for this and recreating the installation faithfully required some curatorial detective work. “This is the first time that the work is being seen since 1964, so it’s quite a discovery,” she explains. “We had read lots of written references to the installation in Mayne’s journals, but it took us a long time to find a visual for it. The real ‘shivers-down-the-spine’ moment in the archive was finding a little comic strip and realising that it was the sequencing for the five channels. He had storyboarded the whole thing, so we’re carefully following his sequencing and timing. “Mayne was thinking about the images within time and a built space and commissioned a score. It’s not just a series of photographs, he was making a whole experience. This was in 1964, so he was really pushing the medium to see what it could do. I think people will be taken aback by the fact that such an extensive body of colour work from the early 1960s, by a celebrated British photographer, isn’t really well known.”

It was originally commissioned by architect Theo Crosby for an international design showcase, the Milan Triennale. It consists of 310 colour slides projected onto five screens, accompanied by a specially commissioned jazz score by British composer John Scott. Images include the leisure interests of a broad spectrum of British society, from working-class crowds at football grounds to upper-class hunting enthusiasts.

All images © The Roger Mayne Archive, courtesy of Bernard Quaritch Ltd

David Clark is a photography journalist and author, and was features writer on Amateur Photographer for nine years. He has met and interviewed many of the world's most iconic photographers and is the author of Photography in 100 Words: Exploring the Art of Photography with Fifty of its Greatest Masters.