Mirrorless cameras with IBIS are making handheld low-light photography easy

With up to 8 stops of image stabilization available today, tripods now feel like an unnecessary piece of kit

Not too long ago I made a confession that I love to travel light when out shooting, and the first piece of kit I consider leaving behind is the tripod. However, that’s been possible only with the advent of mirrorless cameras that feature in-body image stabilization (IBIS).

In the age of the DSLR, the choice of stabilized bodies was very limited. While Pentax did have IBIS, Canon and Nikon both shied away from it, as it was too difficult to stabilize the mirror or pentaprism while also steadying the sensor. Without that combined stability, you’d end up with a jumpy optical viewfinder that didn’t show you the real picture, thus affecting your framing. And so we’ve made do for years now with stabilized lenses.

Mirrorless technology, however, has opened the doors to innovation and IBIS mechanisms have been improving by leaps and bounds, so much so that the Canon EOS R3 boasts up to 8 stops of compensation for camera shake (when paired with a stabilized RF lens). Even a beast like the Fujifilm GFX 100 has IBIS, the first medium format camera to feature it.

The good news is that image stabilization is no longer just in the realm of high-end cameras as those listed above. Camera makers have found ways to make it more accessible, with bodies like the Fujifilm X-S10, Olympus OM-D E-M10 Mark IV, Canon EOS R6, Nikon Z6 and Nikon Z5 also featuring IBIS. Every video-centric camera released in the last couple of years has boasted IBIS for obvious reasons, including the Sony A7C and Panasonic Lumix S5.

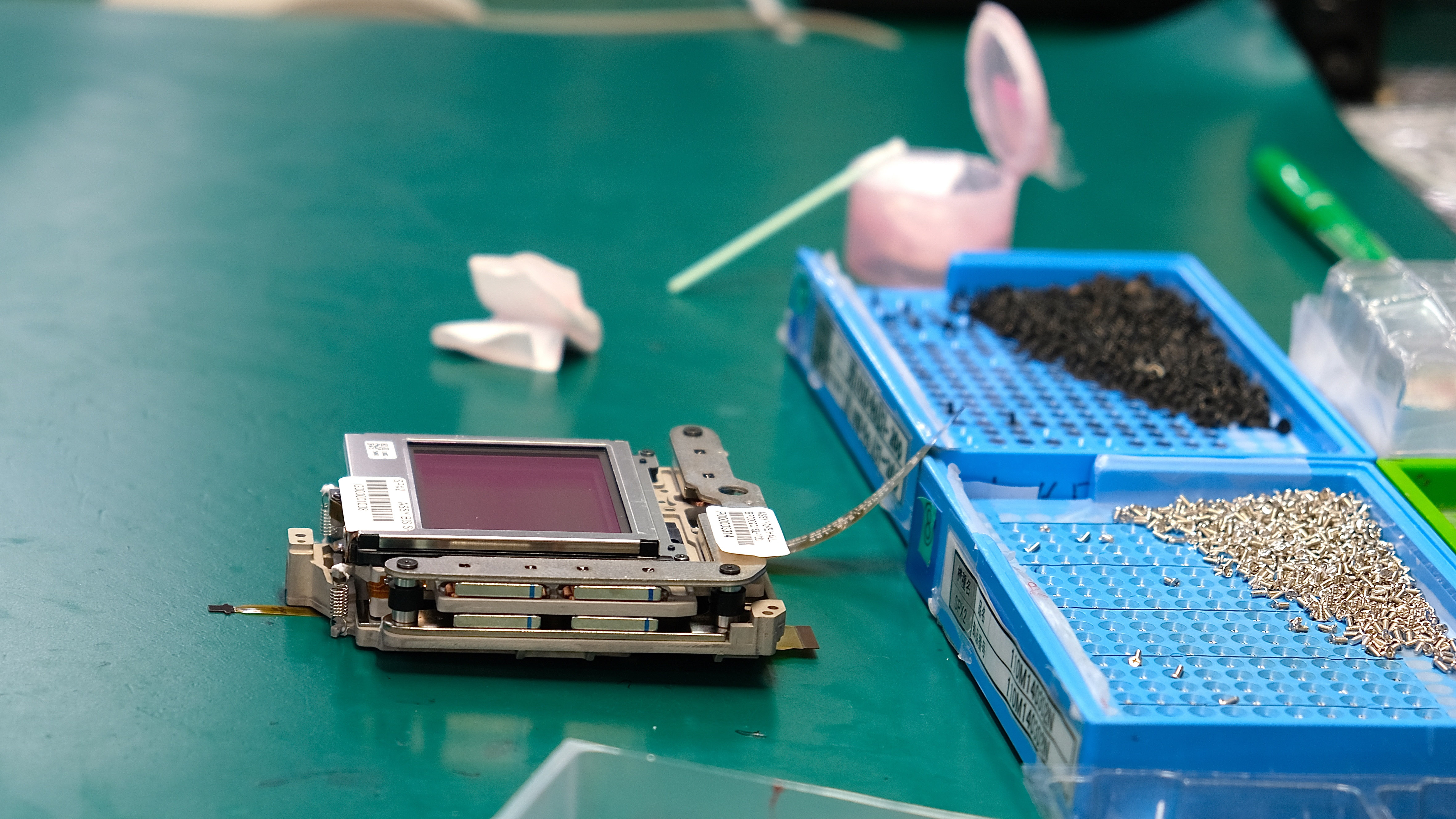

How IBIS works

Without going into too much technical detail, in-body image stabilization works by what is called sensor shifting. Simply put, a mechanism within the camera’s chassis physically moves the sensor a tiny fraction to compensate for camera shake.

The amount of shift is calculated using data provided by built-in gyroscopes and accelerometers that detect camera movement along five axes – yaw (turning on a vertical axis), pitch (side-to-side movement), roll (front-to-back), horizontal and vertical.

Handheld shooting made easy

So, why is IBIS so important? Because it lets you capture shots that you normally wouldn’t be able to in some circumstances, particularly useful for anyone keen on videography and low-light photography.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

One of my favorite events to shoot in Sydney is the annual Vivid Sydney light show (well, it was annual and then the pandemic got in the way) and, considering the best time to see a display like that is after dark, I’d carry my tripod so I could slow the shutter speed down.

Now though, with cameras like the Canon EOS R5, EOS R3 and Fujifilm GFX50S II you can get great handheld shots with shutter speeds of up to two seconds. It even makes astrophotography easier, albeit there are some shots you will still be dependent on a tripod for.

No longer do you need to remember that handheld images are best captured at shutter speeds slower than the focal length of the lens (for example, the slowest shutter speed for a 200mm lens would ideally be no more than 1/20 second). You can afford to be a bit more adventurous.

Anyone who regularly uses fast primes will also find IBIS to be remarkably useful as traditionally primes aren’t stabilized.

There was a time when I wouldn’t have considered it possible to shoot at long focal lengths with IBIS on as lens stabilization has typically been a better option when using telephotos and superzooms. Now, though, it’s possible to use that double stability and get some great results.

That said, I’d still recommend switching off the IBIS if you’re using long lenses as in-camera stability isn’t as effective at longer focal lengths as lens-based stabilization.

Another scenario where IBIS should ideally be switched off is when using a tripod to avoid creating a feedback loop. A camera’s stabilization system can detect its own vibrations even if the camera is still, thus causing motion blur. It can become quite evident while panning, where the IBIS is trying to move the sensor to compensate for the camera and you could end up with wobble effects.

A few scenarios aside, IBIS has truly made it easy for videographers and photographers to get sharp shots without the need for a tripod or gimbal, even while using relatively heavy kits. While I wouldn’t get rid of the tripod just yet (as using IBIS can eat into your camera’s battery life as it’s electronically controlled), the progress in-body stabilization technology has made now makes it possible to capture sharp images at shutter speeds that are three or four times faster than previously possible.

Read more:

Make the most of Canon's IS system

Why digital image stabilization is better than you think

Best camera for astrophotography

Best cameras for filmmaking

Along with looking after they day-to-day functioning of Digital Camera World in Australia, Sharmishta is the Managing Editor (APAC) for TechRadar as well. Her passion for photography started when she was studying monkeys in the wilds of India and is entirely self-taught. That puts her in the unique position to understand what a beginner or enthusiast is looking for in a camera or lens, and writes to help those like her on their path to developing their skills or finding the best gear. While she experiments with quite a few genres of photography, her main area of interest is nature – wildlife, landscapes and macros.