Opinion: DSLRs won’t kill off medium format systems any time soon

Are medium format systems in any danger from high-end DSLRs? Matt Golowczynski reckons the two will continue to coexist

The phrase 'medium-format killer' is one many of us have become used to hearing. It seems that every time a manufacturer releases a full-frame camera with a significantly higher pixel count than the last, any company making a medium format camera is expected to admit their system is no longer relevant.

The logic the supports this idea is easy to understand: why would anyone choose to pay £6000 upwards for a camera that offers the same pixel count as one that’s less than half the price? A camera that’s likely to be bigger, heavier and compatible with a vastly smaller collection of lenses, and from a still-developing system that the manufacturer is more likely to discontinue should sales not be up to expectations?

The winner in such a comparison appears obvious, but there are a number of issues with seeing things from this perspective alone. What follows largely concerns the practicalities of medium format systems, rather than the pros and cons of their image and video quality. That lies outside of the scope of this article, but it's something we'll examine in more depth at a later date.

What works for one person…

… isn't necessarily what works for another. The appeal of a small, lightweight body that packs a high-resolution, full-frame sensor and a range of up-to-date technologies needs no explaining, but not everyone values the same things in equal proportions.

Read more: The best full-frame DSLRs in 2017

Not everyone, for example, needs to be as mobile as you may need to be. A professional studio or advertising photographer working exclusively with a tripod is unlikely to care whether they can shave off a few hundred grams by opting for a DSLR over a medium format system. What they need is a tool that will produce the kind of files that they and their clients demand – and if that’s a medium format camera, so be it.

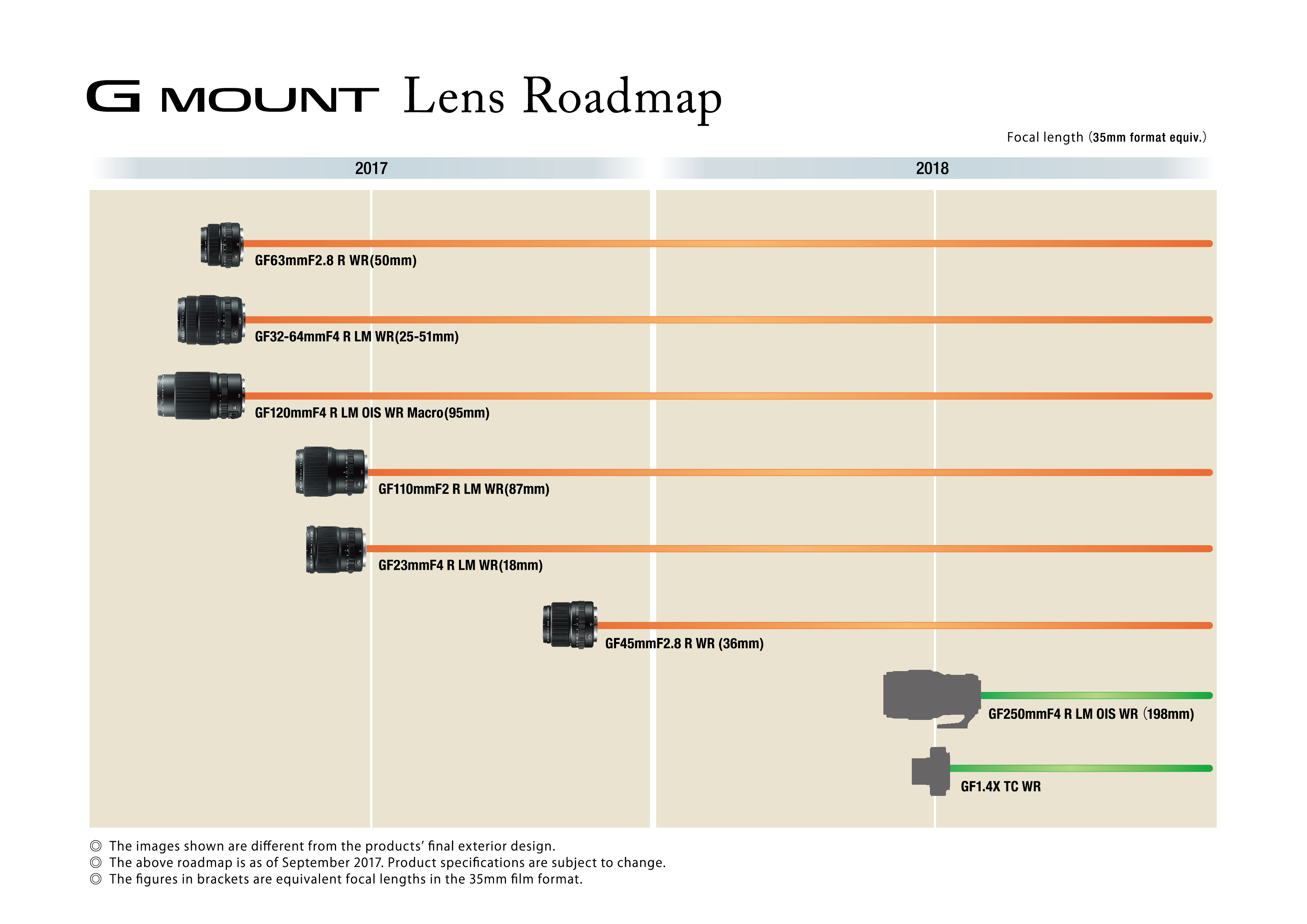

Medium format lens options may be far more limited than those in mainstream DSLR stables, but a camera designed for a niche market is likely have the most key lenses available before too long.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Fujifilm’s GFX 50S model, for example, which was announced only a year ago, already has six lenses available, stretching from wide-angle and telephoto to macro options, and an additional lens and a teleconverter are due to arrive in 2018.

And this is before you look at what teleconverters can be used to mount either older lenses or those from other current systems. That may not quite be your bag, but it's wroth remembering that lens options for any camera are rarely limited to what's developed specifically in that mount.

Pixels are only one factor

The idea that most people are driven to buy a camera based on a simple pixels-to-price or ratio is a strange one. Indeed, some of the most acclaimed cameras in both APS-C and full-frame camps offer a relatively low pixel-count-to-price ratio.

The Nikon D5 and D500 (above), together with Canon’s EOS-1D X Mark II and the Sony A7S II are all excellent, current models, and all doing just fine with 20MP or less (at a time where 24MP is becoming the norm on even budget models). Why's that? Because their target audience doesn't require a higher pixel count, at least not more than the various benefits associated with having a less populated sensor.

Medium format continues to get better

Could we have imagined a camera like the Hasselblad X1D or the Fujifilm GFX 50S until recently? Both are technically medium format cameras, but by eschewing the mirror and viewfinders we would normally expect to see, both companies managed to get size and weight of their respective bodies down to impressive levels, quashing the idea that a medium format camera needs to be a cumbersome brick.

The X1D’s body weighs 725g with its battery in place and the GFX 50S weighs 825g with its battery and card. So how does that compare with some of the most recent high-resolution, full-frame DSLRs? With their respective batteries in place, the Canon EOS 5D Mark IV weighs 890g while the EOS 5DS weighs 930g. The Nikon D850, meanwhile, comes in at 1,005g.

So what about an equivalent compact system camera? The 42.2MP Sony A7R II is currently the closest things we have, and it’s admittedly lighter than the above – but at 625g with its battery and card in place, it only ends up being 100g lighter than the X1D. So, this is hardly a deal breaker.

Of course, these figures do not take lenses into account, but you should get the picture: where portability is concerned, there’s not so much a clear gap between formats, rather a messy overlap between different camera bodies.

Another argument is that the smaller market for medium format cameras means that manufacturers can't quite justify the same kind of R&D as they can for a more mainstream models, and so things move at a far slower pace here.

It’s certainly not uncommon for a medium format camera to already appear dated upon its release. Then again, it’s not like DSLRs develop while medium format systems stand still, it’s just easy to get that impression given the fewer models we have and the frequency with which they’re updated – and because of how much more coverage mainstream systems get.

What we’re increasingly seeing is developments made for one system filter through to another, and this works in both directions. The Fujifilm GFX 50S, for example, sports precisely the same Film Simulation modes as its X series relatives. In fact, it even has a bonus Colour Chrome option that hasn't made its way to X-series cameras yet. It also packs the same X-Processor Pro and the same GUI. Similarly, Pentax’s 645Z also offers a similar GUI and many similar features to K-series DSLR models.

A camera like the Hasselblad X1D is clearly not a tool for everyone, particularly with its tardy autofocus system and 2fps burst rate that seems amusing next to the 7 or 8fps we expect from much cheaper cameras. Then again, it's not trying to be, and neither is any other medium format camera. If you look elsewhere you’ll see it’s actually very well specified, with a flash-sync speed of 1/2000sec (courtesy of lens-based leaf shutters), a touchscreen, built-in Wi-Fi and GPS, a USB 3.0 output, dual card slots, and even both microphone and headphone ports.

And competition will only make things better

Only having one or two manufacturers in a particular field may make things easy when it comes to choosing a camera, but having a variety of players competing against each other with different systems is a good thing. Not only does it make it easier to find a camera more befitting to your requirements, but it also encourages innovation.

After all, manufacturers that have had little or no hand in the DSLR sector have been forced to innovate elsewhere, and the results have benefitted us all. Whether it’s a budget mirrorless camera you can get into your pocket, a full-frame video powerhouse, a traditional DSLR, or a medium-format system that can do even the most intricate landscape justice, there's an option out there that probably makes a lot of sense for your specific requirements – and a lot of that is down to the various ways the landscape has changed over the past ten or fifteen years.

Final thoughts

It’s easy to forget that medium format systems are not intended to be mass-market cameras, and it's just as easy to overlook the fact they they have co-existed with full-frame models for some time. If manufacturers were not convinced that this can continue to be the case, we probably wouldn't have seen Hasselblad, Fujifilm, Leica and Pentax innovate in the ways they have over the past few years.

And prices, eventually, will fall. Medium format camera might still be out of the reach many, and the physical size of their lenses may continue to put some off, but if we look at how full-frame cameras have developed we have an encouraging precedent.

The first so-called “affordable” full-frame DSLR was the Canon EOS 5D, and this arrived with a $3500 RRP. Today, you can get a brand new full-frame camera for almost a quarter of the price, and if you’re happy with a second-hand model you can get it for considerably less.

Today we might have medium format models like the Fujifilm GFX 50S and Hasselblad X1D, but who knows where it will go from here?

The former editor of Digital Camera World, "Matt G" has spent the bulk of his career working in or reporting on the photographic industry. For two and a half years he worked in the trade side of the business with Jessops and Wex, serving as content marketing manager for the latter.

Switching streams he also spent five years as a journalist, where he served as technical writer and technical editor for What Digital Camera before joining DCW, taking on assignments as a freelance writer and photographer in his own right. He currently works for SmartFrame, a specialist in image-streaming technology and protection.