Peter Dazeley: Photographing London's Theatreland

Pro photographer Peter Dazeley discusses his recent project

Peter Dazeley has worked as a fine-art and advertising photographer for almost 55 years, and was recently awarded the British Empire Medal in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours for his services to photography and charity. His most recent book, London Theatres, is published today. We caught up with him to discuss the capital's hidden treasures, as well as how Nikon DSLRs changed his photography and what young photographers should be doing to get themselves noticed.

Portrait of Peter Dazeley by Rankin

This is the third book of its kind for the same publisher. How did it all start?

It started in 2010. I have an apartment on the Thames, between Vauxhall and Chelsea Bridge, and it overlooked Battersea Power Station for years. As an advertising photographer I’m always looking for interesting people, things or places to photograph, so I blagged my way in for the day.

It was quite fun, and I ended up with a remarkable set of images of what’s left of the grandeur of the place: the architecture, the art deco and so on. My agent thought it was interesting, so we put it out as a news piece and it got well received.

Creative Review picked up on it and it went viral. It was an exciting thing for me to go and do, so I thought maybe I should try to blag my way into a lot of interesting places, and record my London as it stands in the 21st century.

The first book took me four years to do. Getting into some places was battle – the Ministry of Defence, for example; I got permission, then it was taken away. Most people wouldn’t be able to get into many of these places, so I went back to the publisher with an idea about a second book about uncovering London, with all the interesting places you can go and visit and details on how to do that. That was published in 2016 and again has been very successful.

The publisher then came to me with an idea of a theatre book. I already had six or eight different theatres from the first couple of books, so I had a starting point that made it more effective. It took off and I did it in about nine months.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The writer, Michael Coveney, who has brought the book to life, managed to get Sir Mark Rylance to do a foreward for the book, and it’s a beautiful piece. I would have been grateful for two paragraphs but he gave us about 1,500 words. For someone who is incredibly busy he obviously cares, which is lovely.

Do you think the physical photo book still has appeal in a digital world?

Absolutely. The books have been very intriguing to lovers of London, tourists, historians and architects.

Are you a fan of the theatre yourself?

Yes, I go regularly. My daughter has decided she wants to be an actress, so I managed to get her a week’s work experience at the Theatre Royal Haymarket and a week at the Palace Theatre. She's only 16 at the moment but the Palace Theatre offered her a job eventually. I made lots of friends in the theatres, which was nice.

Was there any particular theatre that stood out for you, photographically?

There were some beautiful ones, yes. The Theatre Royal Haymarket is very beautiful. Also, the theatre that’s playing The Mousetrap [The Ambassadors Theatre]. It even has a royal box right at the back of the stalls so they don't get looked over, which is interesting, but then they don't have a good view. Meanwhile, the royal box at the Theatre Royal Haymarket is almost on the stage!

Also the Royal Opera House – just wow. And somewhere like Wilton’s Music Hall; it’s just wonderful you have this real music hall that’s been restored in such a nice way, with all the brickwork exposed. And, above all possibilities and reason, it’s still functioning.

Did you have a particular focus for the book?

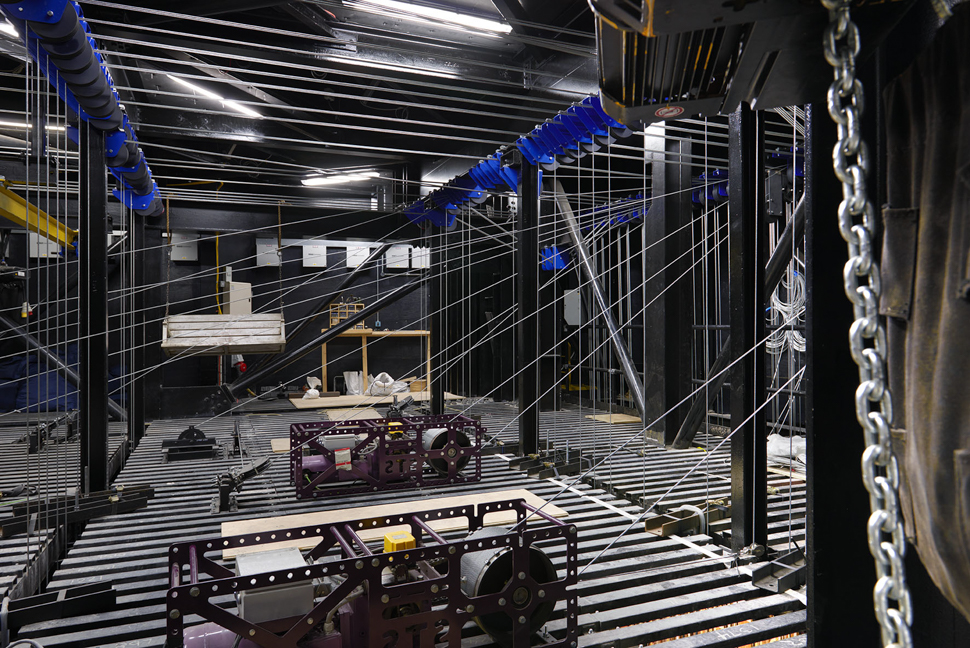

One of the things I was desperate not to happen was to have endless pages of red seats. The idea was to try and photograph behind the scenes: the fly floors; under the stage; orchestra pits; make-up rooms; dressing rooms; trapdoors; wig rooms; and what goes on backstage. The images that appear in the book are just a speck of the ones I took in each theatre.

I suppose those are the more interesting images because people never really see those things, whereas anyone can walk into a theatre and appreciate the main auditorium itself.

I don’t think we do appreciate it. Having been to a great deal of these theatres, to go back and photograph them was a different experience. You discover fascinating things too, such as at the New Wimbledon Theatre, which I’ve been to many times, had to have its globe taken down during the war because the Luftwaffe was aiming at it to come into London. And it also used to have pink crocodile seat covers. You discover some weird stuff!

Were there any particular surprises that you came across when shooting the hidden parts of London for the first two books?

Tons of things. Under the Ministry of Defence there's part of the only remains of Whitehall Palace, and it's Henry VIII’s wine cellar. It was picked up, put on rollers and encased, and moved there by Queen Elizabeth I. And you can’t get in there. First they said I could get in, then they took it away. Not many people get to see that.

There are wonderful things like Open House in London. The Mason’s building in Covent Garden [Freemasons' Hall], which I’ve walked past millions of times. but never realised what was inside. It’s like seven acres in there, and it's the most beautiful building. They’re the most generous people and were kind enough to allow me to have my book launch there. Apparently they’re the biggest givers to charity after the lottery, but they don’t have very good PR so nobody knows!

How do you approach a building you’ve not been in before? Would you walk around the entire building first and make notes?

It depends. I can work quite quickly, but you normally don’t have the run of the building on your own. You would have electricians or manager who would come with you. I was left alone in some places, but normally they have someone who knows the history. I would get them to show me what they think was interesting, then I would ask if we could look under the stage and elsewhere.

Can you run through what gear you use?

For my first two books, I mainly shot with a Hasselblad camera and a big 40mm Distagon lens, with a laptop on a stand and an assistant. It was heavy tripod that goes up a long way and it did my back in.

Then I bought myself a Nikon D800 and D810, which completely revolutionised the way I work because I could work on my own with a simple tripod, without a laptop. I started off with the D800, but I thought I ought to buy another body in case anything happened – but I’ve never had to use it because it’s so reliable.

As a photographer who started of with glass plates all those years ago, you appreciate how technology has changed. I was blown away with how the D800 would deal with long exposures because we didn’t use any lighting. I think we got up to about half a minute [of exposure time] at the London Palladium because it was so dark.

Another thing that impressed me was how the D800 would cope with mixed lighting. Years ago, if you shot on transparency film and you had fluorescence in the scene, everything would go green. But Agfa had a particular roll of film that was so off balance that it would come in at the right colour! The D800 seems to cope brilliantly with a bit of tungsten, a bit of daylight and maybe a bit of fluorescent light.

I don’t understand the love of film; I’m clearly out of step with the film intelligentsia, because I just don’t get it. Film was never sharp. We never viewed it in the same way, we could never see what it was really like, and the quality is neither here nor there. Most people who shoot on film immediately scan it, so it immediately becomes a second-generation thing. I just see a digital file as a negative, from which you have the choice of doing so much.

What lenses did you use for the images in your book?

They are the Nikon 14–24mm f/2.8G ED and the Nikon 24–70mm f/2.8G ED.

No Perspective-Control lenses?

No. I spirit-level the camera to try and get it all straight, but sometimes you have to move it up a bit to get everything into the frame.

What’s your approach to processing?

We try to get it as accurate as possible in camera. Clearly if you have extremes in the scene, for example, I might take a bunch of exposures to deal with blown-out windows. But after we've assessed them on one computer, then they go through to another computer upstairs and I sit with my retoucher. We try and have every upright parallel, but it fascinates me how you can do such extreme straightening of verticals in Photoshop.

You were born in London and have lived here your whole life, so presumably you will have been familiar with some of the places you photographed. Do you think that affected your approach?

It was just a hobby, just a fun adventure to blag my way into places, but not unfairly because we were giving these places high-res images to use in return. You know, to get to the top of Big Ben or top of Bow Bells or Whitechapel Bell Foundry; they’re not places I’ve been to before.

We Googled them and saw what kind of images were out there, and how things could be improved. But it really was an adventure; if you go underneath Bow Bells, for example, you're essentially in the 10th century.

Whitechapel Bell Foundry, which has now been sold and now may come an end; they’ve been making bells in exactly the same way since the 1500s. It was a wonderful thing to see them casting a bell, and how they manufacturer them.

Places like Harrow School, which has produced eight prime ministers and people like Benedict Cumberbatch. They invented squash there, play rackets, fives – all kinds of different games I didn’t know about. Lord's, too; we’re sending out our best cricket team in the world, but the changing rooms are so basic. You’d think "this isn’t the way to send out our cricketers!”.

Places like the Midland Bank, that has now become the Soho House hotel, was an amazing place to photograph. You've got a banking hall the size of a football pitch, and you'd be utterly sideswiped as you walked in. The management suite of offices, which were designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, have bespoke furniture, with covers at the top to put your top hat in and a drawer at the bottom to put your cane in. This really was a different world. A lot of the buildings I photographed won’t exist in years to come, which is why it’s such an interesting book.

There are lot of funny things to show people in the previous books, and it’s the same with theatres. There are still two theatres left with thunder runs, which are these big wooden contraptions that run down the side of a theatre. When they needed the sound of thunder, they would just put a cannon ball down it and it would crash down. A lot of the technical stuff in theatres was designed by sailors, and you can see that in the rigging systems. You’d have to read the book to know why sailors got involved, but that was another interesting fact.

You mention a lot of these places won’t exist anymore. Did you feel a sense of responsibility to try and capture them as best as possible?

I just really wanted to share it. I don’t know whether the pictures would be donated at some time in the future, but it’s just lovely to share the things I didn’t know about in this wonderful city. But I don’t think I have a responsibility – I’m just trying to produce the best book I can.

With some of the theatres it was quite difficult because they have very big productions and rehearsals. It was difficult for them to find the time to let me loose. In some, like the Royal Opera House, I only had an hour and a bit. A lot of theatres do tours, though, so you can pay to go and see them for yourself.

What places did you come across in London that are accessible but under-appreciated that you would recommend visiting?

Well, Freemasons' Hall in Covent Garden has a museum and is open every day of the week. Somewhere like Theatre Royal on Drury Lane is also a great place to go for a tour. The Charterhouse in Smithfield is also an amazing place, and it's now becoming part of the Museum of London.

You’re quite active on Twitter and have a strong following. What do you think the key is to cultivating this kind of social audience?

I try to find interesting things, but it’s very difficult to know what will catch people’s attention. Out of the blue something will get a huge amount of interest. Yesterday I put out a news story about someone that was selling the album Mark Chapman got John Lennon to sign the morning before he went back to shoot him. And I thought it was an amazing story, but nobody was interested! Twitter is a bit of fun but I don’t think it makes much difference, whether people give you work or not.

Obviously you have decades worth of work behind you, but for someone looking to promote themselves, would you think social media would be a good tool to use?

I think it depends on what you’re working in. If you went to a degree show for graphic design, for example, a design company might hire straight off what was on the wall. It you went to photography exhibition, it wouldn’t be the same as they’re just aren't the jobs available. It’s very difficult in photography to make contacts; if you want to see an art buyer or an ad director, you’d find it incredibly difficult.

In photography, what people should be looking for is to be different, to come up with a new technique. We've had cross processing, limited focus and x-ray imaging – you want to be the first doing this, not the last! And it’s impossible to get some students to think about it, but someone going to do it. All I would say to kids is to experiment like hell, make a mistake, be off the wall. It’s fine if you make a mistake, just don’t make the same stupid mistake twice.

Looking at photo books, too; this is another thing kids should do. We’re all influenced by the images around us. If you see someones great image, don’t copy it but make it your own. Take an idea and take it further. Experiment like mad.

There was a period in my life when we used to have endless university students coming to do work placements throughout the summer, and it all came crashing to an end. I had a more mature student who came to spend a week with us, and he ended up annoying everyone. You’d ask him whether he knew about copyright, and he’d say he did, but really he didn’t.

At the end of the week I asked him if he had bought his book in, and he looked me straight in the eyes and said that he hadn’t brought his book in because he thought it might intimidate me. And that really was the end of doing that. If you have someone coming to do a placement, you have to spend time explaining things, but I lost the point after that.

You can see some kids have got it. Just silly things, like not waiting for someone to ask for cup of coffee, but just getting in there and doing it. We had one who’d never made a cup of tea or coffee in his life! It’s easy to stand in the corner, or find a seat and just put your hands in your pockets, but you need to interact. If you’re the person who can bring something to the party, then maybe when they’re hiring an assistant they’ll remember you.

You’re also know for your nudes work. Do you think you would be able to take the same images today? Or do you think it would be more difficult?

You tell me - are the images inappropriate now? That’s a good question. I’ve never really thought about it. To me, the best thing I can ever do is to create emotion.

One of my favourite things I ever did was when my son was born. His mother had a caesarean section, and we were all gowned up in the operation theatre. I explained to the surgeon that I was a photographer and asked whether I could take a picture. I had this tiny point-and-shoot camera in my pocket and I just got two frames – and I ended up with this image, which is of his first breaths.

It caused a lot of aggravation, and a lot of people didn't like it – and to me that was kind of lovely. To create something that creates enough emotion in people enough not to like it is cool. So maybe having a camera with you at all times is a good thing.

What are your plans? Any unrealised projects?

I guess the commissions will slowly die down. Getty is my main source of income, and it's fun trying to second-guess what people will want next. I was reading the other day that one stock library only sells one in every hundred images that are uploaded. So, there’s very little return, and a lot of stock photography is now done by designers and art directors. Still, if you’re an amateur it’s a great way of getting your work out there – and maybe it will sell and you’ll earn a little money from it.

London Theatres, written by Michael Coveney and illustrated by Peter Dazeley, is published by Frances Lincoln.

The former editor of Digital Camera World, "Matt G" has spent the bulk of his career working in or reporting on the photographic industry. For two and a half years he worked in the trade side of the business with Jessops and Wex, serving as content marketing manager for the latter.

Switching streams he also spent five years as a journalist, where he served as technical writer and technical editor for What Digital Camera before joining DCW, taking on assignments as a freelance writer and photographer in his own right. He currently works for SmartFrame, a specialist in image-streaming technology and protection.