Pictures of Paris under lockdown rekindle golden age of French street photography

Covid-19 restrictions gave Tony Maniaty a once-in-a-lifetime chance to recreate the golden era of French ‘humanist’ photography

There’s no question that the Covid-19 pandemic has been, at best, disruptive for millions of people and, at worst, tragically disastrous for millions too. However, no matter how dark the clouds, there have been silver linings… for example, unexpected commercial opportunities, enforced changes of career that have proved to be fortuitous, and a return to more locally-focused activities with a range of benefits for these economies and communities. The picture for photographers too, has been about light and shade – some sectors grinding to a complete halt as a result of lockdowns, but new possibilities emerging from the many unusual situations that have become part of the Covid ‘experience’.

For the documentary photographer, there have been many Covid-19 stories to tell as both individuals and whole societies have been forced to adapt to changes in lifestyle far greater than any have experienced before. And stay-at-home lockdowns transformed towns and cities around world, turning bustling locations such as shopping malls, railway stations and airports into eerily deserted scenes, reminiscent of dystopian movie sets. For the street photographer, these were opportunities not to be missed.

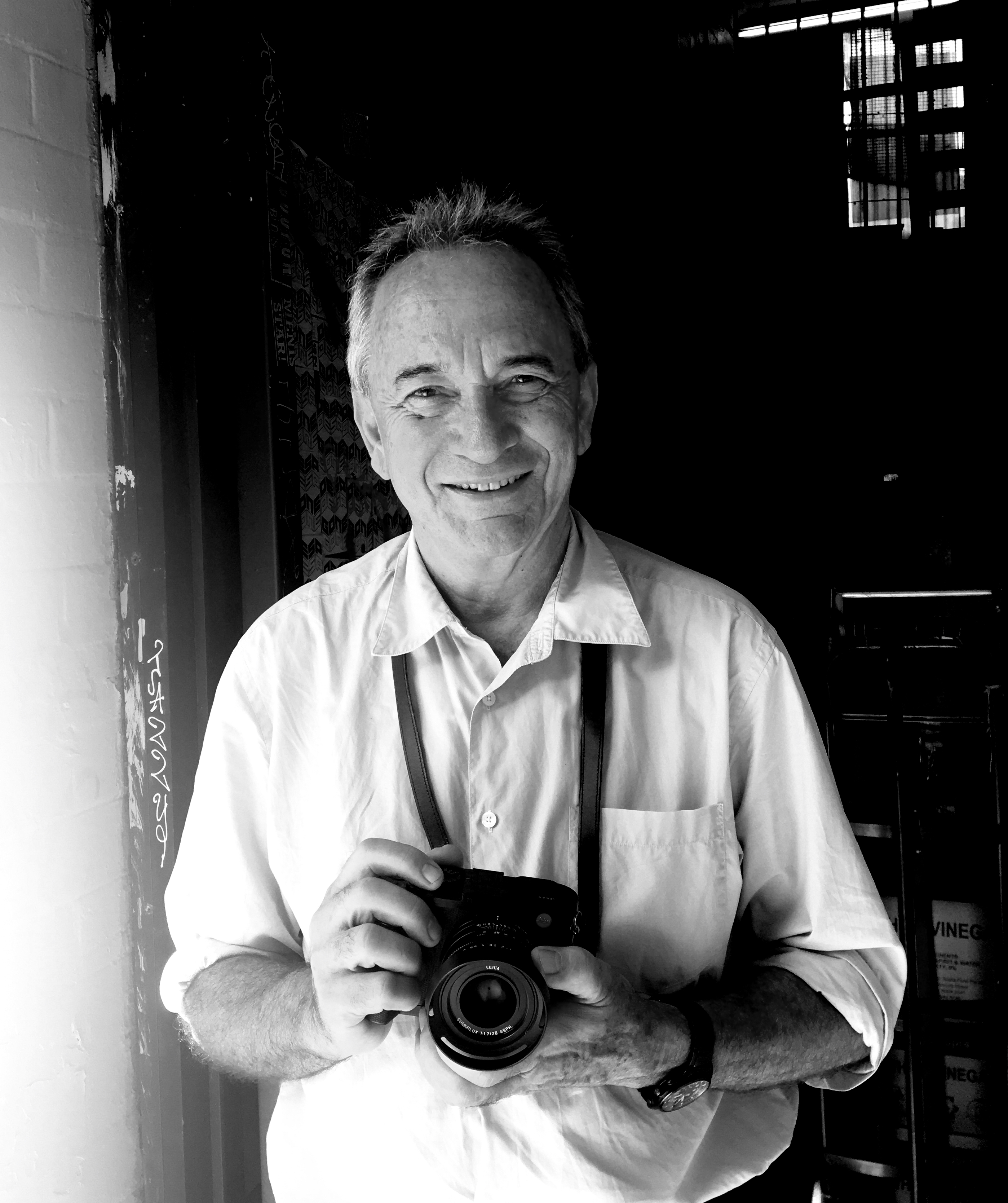

For Australian journalist and photographer Tony Maniaty, there was the added appeal of finding himself in a city perhaps best known for its intimate interactions with its citizens and visitors, making its suddenly much-quieter boulevards, parks and cafes look even more starkly surreal.

“Like many photographers, I’ve had a lifelong affair with Paris,” he explains. “The city is so textured, layered with energies and culture and life. And, of course, the French pretty much invented photography, starting with Niépce and Daguerre, so there’s a great love and appreciation of photography, with galleries everywhere. It’s photo heaven, really.

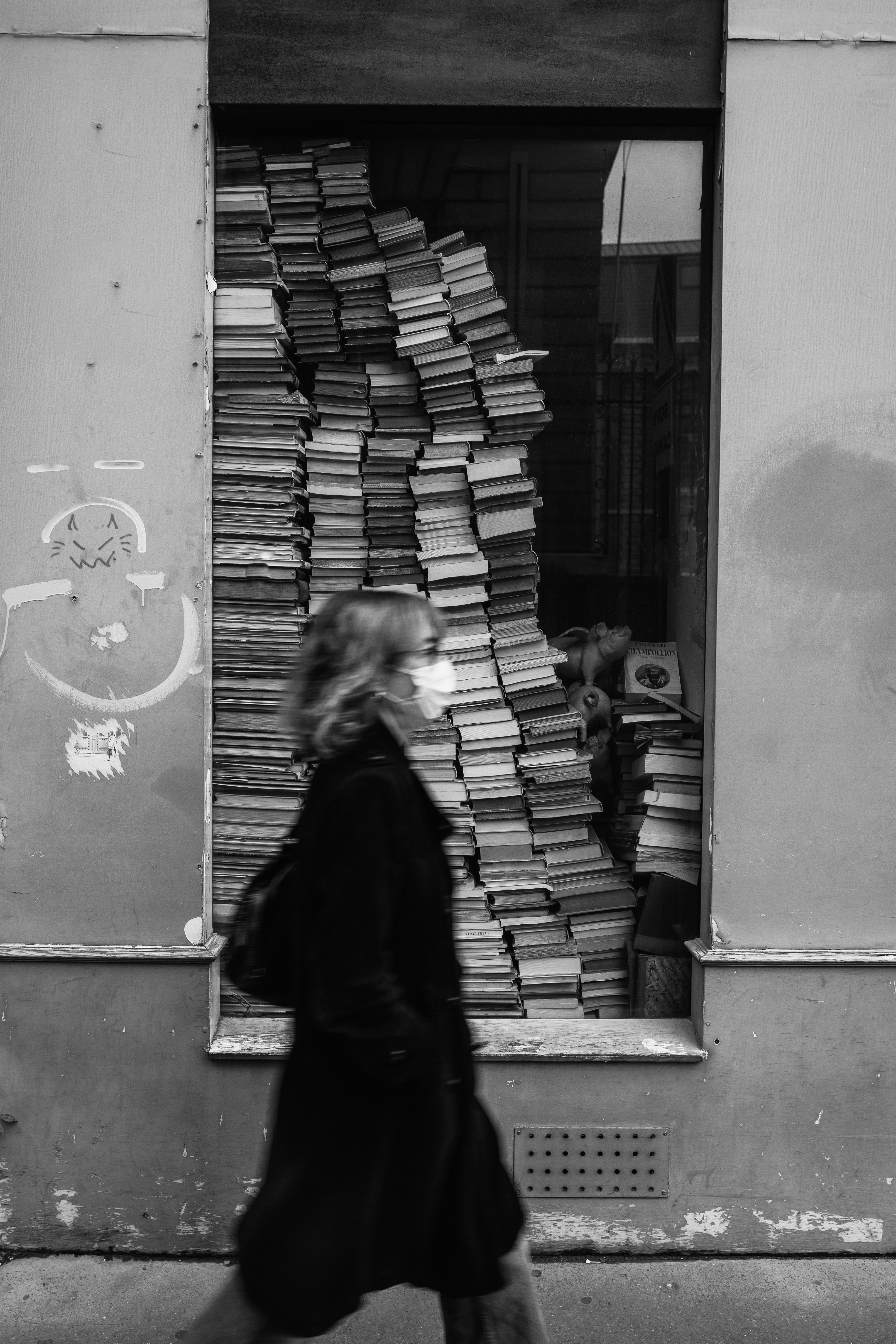

“I went to France for an extended stay in early 2020 and Covid followed me there. I quickly hit the streets, determined to capture the Parisians in this odd world of no tourists or traffic… very much like the Paris of the 1950s and the ‘golden era’ of French street photography when greats like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, and Willy Ronis were doing their best work. It wasn’t only this retro-façade of Paris, but equally the mood… not unlike the post-war spirit of coming together to help rebuild France. They were determined to keep going and not to be defeated by Covid. You could see it in their faces, even behind the masks. I felt they were defying not only the pandemic, but the homogenized nature of modern life where everything starts to look the same. I tried to capture both the individualism and the sense of a common humanity, and – given the city was less frenetic than normal, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity – also to pay homage to that post-war French ‘humanist’ photographic tradition.

“While the media generally focused on the worsening crisis, my intention was to photograph Parisians reclaiming the boulevards and backstreets – in this historic moment of calm – as their own. I wanted to capture fragments of life – less about loss than discovery, and less about gloom than optimism. Day after day, I felt quite privileged to be there. In a way the project ended up being a love poem to Paris, the ‘City Of Light’ and still one of the most beautiful places on earth. As Bogart says in Casablanca, ‘We’ll always have Paris...’.”

Tony’s love affair with photography started when he was a teenager and he purchased his first camera, a Pentax 35mm SLR, when he was 16. This was funded from working at the local news agency, where he discovered the British photography magazine Creative Camera, which introduced him to classic monochrome photographs by Cartier-Bresson, Bill Brandt and other masters, igniting his passion for street photography… although he prefers to call it “human photography”, which he defines as “the ability to capture humanity where we find it”.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

“I started the photography club at my high school near Brisbane and, a couple of years later, I scored a journalism cadetship with ABC News, working in radio and television. But my passion for photography remained. I bought my first Leica, an M3 with an Elmar 50mm, for $150. Back then, Nikon and Canon were the latest things, so you could pick up Leicas for a song.

“The next major step came in 1977 at the Australian Centre For Photography in Sydney, where I met my mentor, the American photographer Ed Douglas. He introduced me to the gritty street work of Gary Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and, importantly, Robert Frank. When I saw Frank’s work in The Americans – still regarded as the greatest photography book ever – I knew that was the style and form I had to follow. I’d found my photo-god, so to speak.

“My ABC News sub-editing shift ended at 1.30pm and afterwards I’d roam inner Sydney, capturing what was, back then, quite tough street life. Surry Hills and Kings Cross were seedy ‘no-go’ zones, and not the chic neighborhoods they are today. In 1978 I held my first solo exhibition, Travelling Pretty Slowly, in Canberra. I sold two prints.”

Visual Storytelling

Having come from a news background, Tony is well aware of the media’s role in exposing the injustices of the world.

“I know that powerful current affairs reporting can lead to important change. But I also believe that photography can bring people together, and describe a better world in which differences are celebrated and shared rather than being a cause of division. That’s the ‘upbeat’ that drives my work and the images I’m looking for. These days, I’m on the streets anonymously, not so much investigating as capturing daily life, a two-way process that’s positive and energizing.”

Tony contends that the key to effective photojournalism is using images, either singly or in sequences, to tell human stories.

“Photojournalists don’t simply ‘take pictures’, we’re visual storytellers, and what makes us special is our ability to make every story our own. Without stories, who are we? I drilled this into my UTS media students. Slowly it sank in.”

He also believes it’s important to have a good knowledge of the history of photography to understand what’s gone before and how it can still be both relevant and informative today.

“To effectively tell stories, we need to know the stories that came before. Over the years, I’ve explored the history of photography. It’s been an enormous learning curve because there’s so much there to draw from and appreciate… a treasure chest of stunning ideas. Take a look at Cartier-Bresson’s contact sheets and observe a genuine artist at work. I’m equally inspired by the approach of Raymond Depardon who, at 78, is still knocking around France with his large format camera, taking incredible photos. His images embrace the entire history of post-war France, which is some legacy.”

Curiosity and humor

So what, then, are the key attributes of a photojournalist?

“I believe there are three key things – and I’d say the same for journalism generally. Firstly, an intense curiosity about the human condition, then a love of language, and, finally, I think you have to have a sense of humor. Let’s break that down. Obviously, street and documentary photography demands curiosity about people, but I’d argue so does portrait or fashion photography. The great Hollywood director Billy Wilder said all his movies boiled down to a single idea, ‘What makes people do the things they do?’ Anyone who wants to be an artist has to peel back the surface of things and see what’s really there. Which leads to language… a visual language if you’re a photographer. You need to know intuitively how to compose a shot, how to read the existing light, how to make a moment not only ‘speak’, but ‘sing’. And, in the case of street work, you need the ability to anticipate when things are ‘about to happen’… then the camera becomes a subconscious extension of your visual vocabulary.

“And humor? By nature, we humans are contradictory, behaving in eccentric and erratic ways – you never know for certain what’s coming around the corner. A great example is the Magnum photographer Elliot Erwitt – still going strong at 92 – who specializes in people and their dogs. All his images are slightly crazy and ‘unexpected’.

“The world is full of odd behavior and irony. You have to go looking for it, but if you don’t have a sense of humor – the juxtaposition of the sane and the irrational – you won’t find it.”

Technology and credibility

Technology has dramatically changed all aspects of photographic practice over the last couple of decades and, in photojournalism, it’s made it much easier to capture both stills and video even in challenging locations. But do these efficiencies come at the expense of more intensive and investigative reporting?

“When I began in TV journalism, we were using World War Two-era Bell & Howell and Arriflex 16mm film cameras. Then we transitioned to bulky videotape cameras. Satellite bookings to send material were hugely expensive. In the 1990s, I was the Paris-based correspondent for SBS, covering all Europe, and the gear for our three-person crew required five or six hefty cases. Today, a correspondent’s entire kit fits into a backpack, with spare room for a sweater! They’re shooting reports on iPhones and sending them back to base by Dropbox. So, technologically speaking, in video and stills, we’ve come a long way. Are the stories any better? We could argue about that all day, but technology has definitely boosted the ‘need for speed’ and the ‘volume against quality’ demands, which inhibits deep, accurate reportage in the field. And with the exponential rise of the internet and social media, plagiarism and keeping track of rights is a nightmare.

“One of the ironies of our ‘Photoshop-able’ world is that image manipulation has enhanced the output of creative photography, but also threatens the credibility of documentary work. It’s a debate that goes all the way back to Robert Capa’s famous image Falling Soldier in the Spanish Civil War – fake or real? But now the questioning of authenticity has been sucked into the highly politicized arena of ‘fake news’, where everything is suspect and challenged. Authentication technologies will help, but I can’t see that reversing the trend. People will believe what they want to believe. This increasing lack of faith in what was previously accepted as factual content is dangerous to the whole profession of news and documentary photography, and to democracy itself.”

It’s all about The Story

While he appreciates the traditional look of film – still quite widely used in street photography – Tony thinks that the conveniences of digital capture and editing are ultimately the more advantageous means to the end.

“I’m currently using digital Leicas – the M10 and the Q which are both superb cameras – but there are so many great cameras out there now. The purist in me agrees that film still looks better in a perfectly developed and printed gallery edition, but the pragmatist in me says that, firstly, most viewers can’t see the difference, and, secondly, do I really want to spend days in a darkroom with lung-damaging chemicals doing what Lightroom or Capture One do with greater speed and flexibility, and at a fraction of the time and cost? What matters ultimately isn’t the technology, it’s the story – what it’s about, not how it was made. That said, I’ve aimed to give my Paris images a more classic ‘film’ look, in style anyway.”

We’re visual storytellers, and what makes us special is our ability to make every story our own. Without stories, who are we? We’re visual storytellers, and what makes us special is our ability to make every story our own. Without stories, who are we?

In terms of his approach to street photography, Tony says, “When you’re chasing the spontaneity of the streets, there’s no way of knowing if there’s a great shot to be had or not. You have to be all set and ready to grab anything. I normally shoot in monochrome and search out shadows, so early morning and late afternoon are my precious hours. Around 6pm also happens to be a good time to wrap up and stop at a Paris café for an aperitif!”

Being both a writer and a photographer gives Tony Maniaty the scope to tell stories in a number of ways and he believes that balancing text and images can be very powerful, but he also contends that one strong image still has the potential to be equally effective.

“Photography – as presented or published – is a broad church. Some insist on a sole image telling the story without explanation. Some choose a photo essay or gallery sequence, believing that the flow of images will ‘tell the story’. Others expand their work with text. My Paris project, Our Hearts Are Still Open, combines these concepts with solo images posted on Instagram – often very soon after they were taken – a gallery show with carefully-sequenced images, and a photobook (which is still in development), with accompanying text – a short essay by me, and a longer interpretation by the philosopher Raimond Gaita who’s best known for his memoir, Romulus, My Father.

“There are great examples of this, notably Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a collaboration between photographer Walker Evans and writer James Agee, exploring dustbowl America in the 1930s Depression.

“Getting the text and images in balance is hard but, for me, when it works, it’s magic. Being able to blend images and text obviously broadens your market, but I think there’ll always be room for a great standalone image. The history of photography is based on such moments.

See also

Best Leica cameras

Best Leica M lenses

50 best photographers ever

Tony Maniaty is a photojournalist, author, and academic based in Sydney and Paris. His career has encompassed broadcasting, fiction writing, lecturing, and photography. He was Executive Producer of ABC’s 7.30 Report and Associate Professor of Creative Practice at the University of Technology Sydney. He holds a PhD in Media.

His latest project, Our Hearts Are Still Open, features images of Paris taken during the Covid pandemic. A photobook of his Paris images – with an essay by Raimond Gaita, philosopher and author of Romulus, My Father – will be published by StudioTettix later this year.