Photographing the final days of steam railways: a tale of two teenage brothers

Two brothers, teenagers in the 1960s, sated their passion for the steam locomotive by capturing them in a massive collection of black-and-whites

A trusting mother who allowed her two teenage sons to roam the New South Wales railway system in Australia unaccompanied during the 1960s unwittingly enabled the compilation of a unique historic photographic record of the last days of steam. Five books down – and with a sixth in production – the Wheatley brothers are still mining their remarkable archive of railway portraits.

This article originally appeared in Australian Camera magazine, one of Digital Camera World's sister titles Down Under. Click here to find out more about Australian Camera magazine, including how you can subscribe to the print issues or buy digital editions.

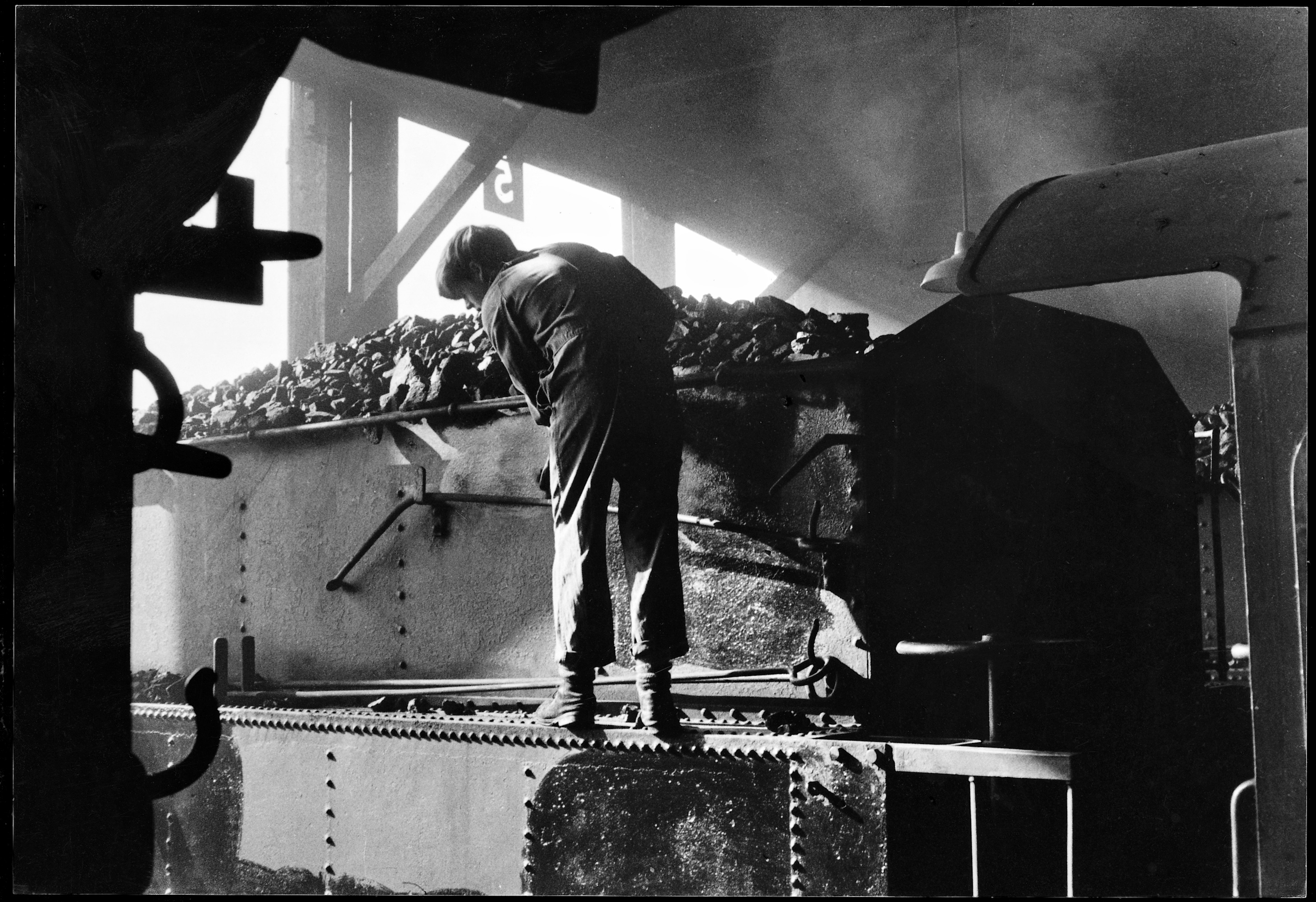

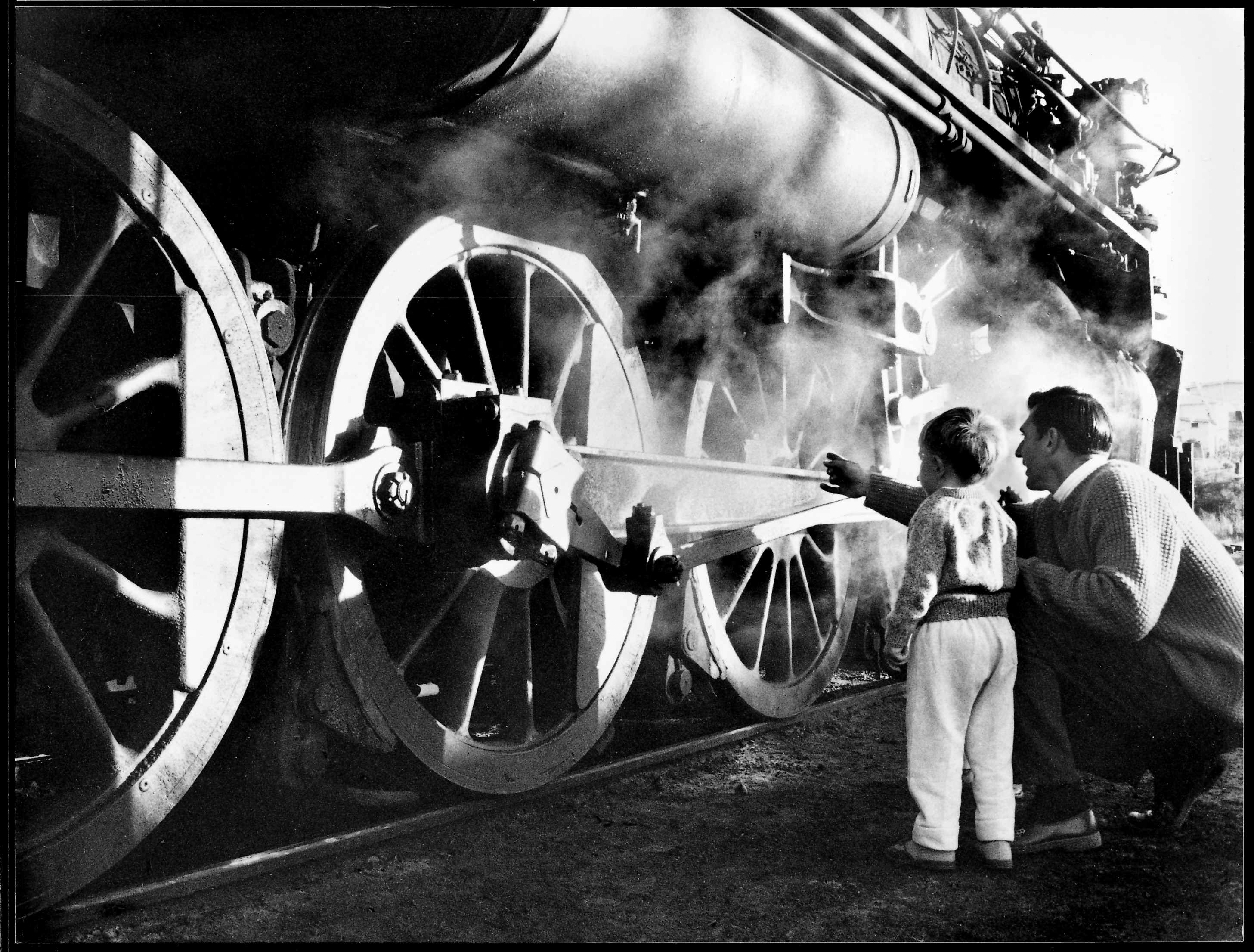

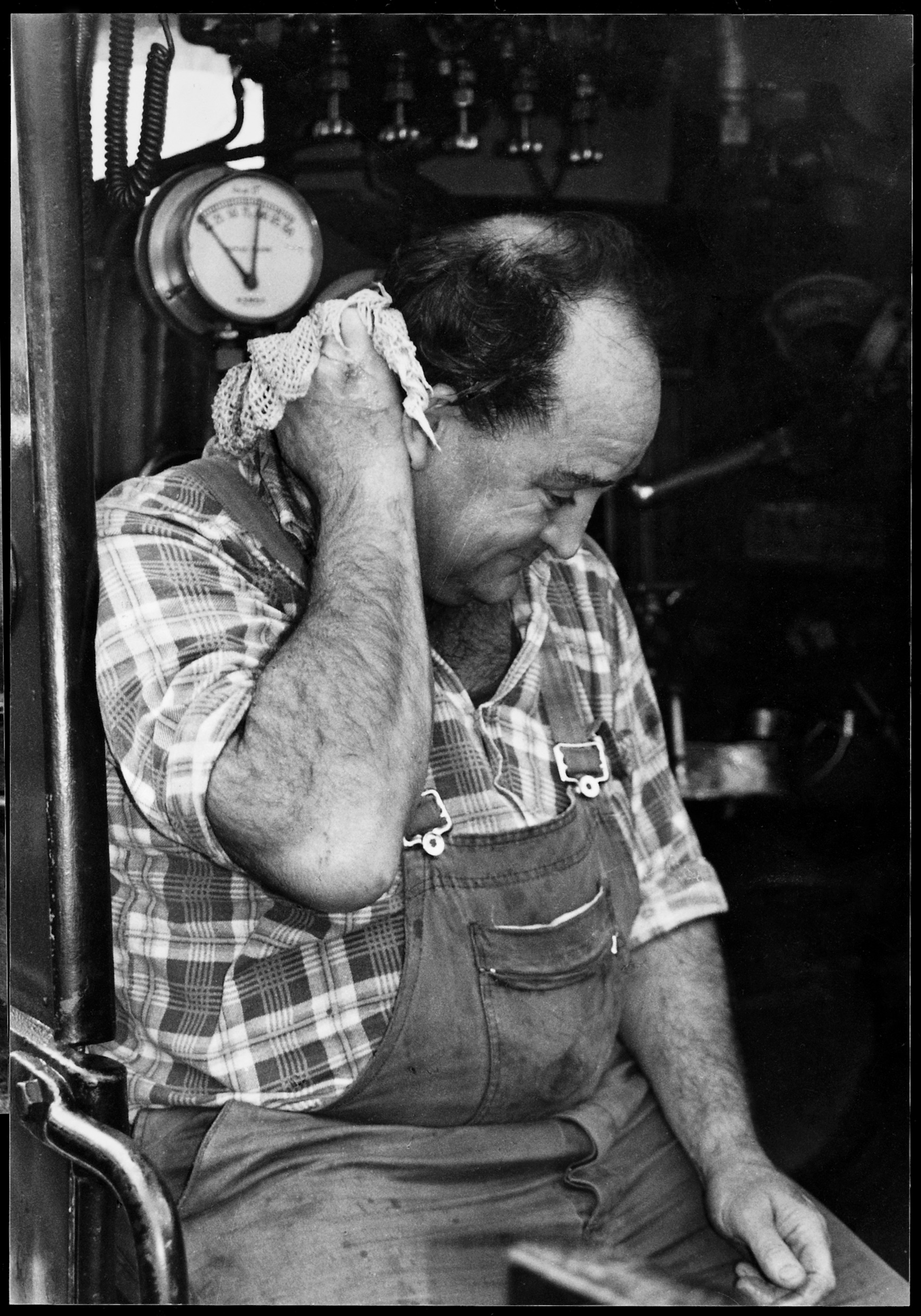

The steam train – or more precisely, so as not to upset the true enthusiasts, the steam locomotive – has left a lasting impression on those who can remember them when they were an everyday occurrence. And the handful of preserved examples still draws a crowd wherever they go. They are a truly dynamic multi-sensory experience… sight, sound, smell and touch; maybe even taste too. Consequently, books celebrating the steam era continue to be published, but just about all of them concentrate on the machinery rather than the men (and it was all men back then) who operated and maintained them. Without the human involvement, the steam locomotive was just a static lump of cold metal.

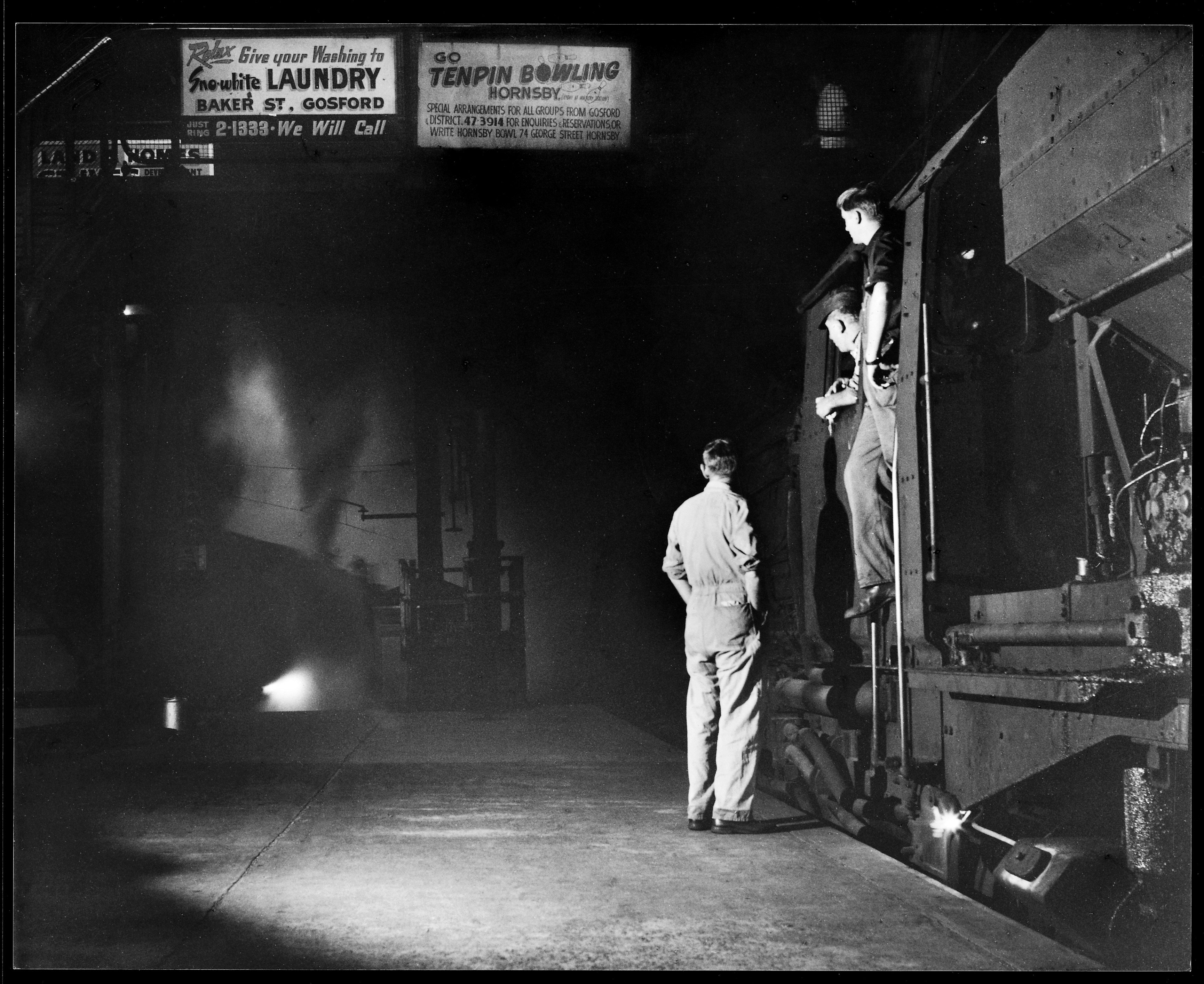

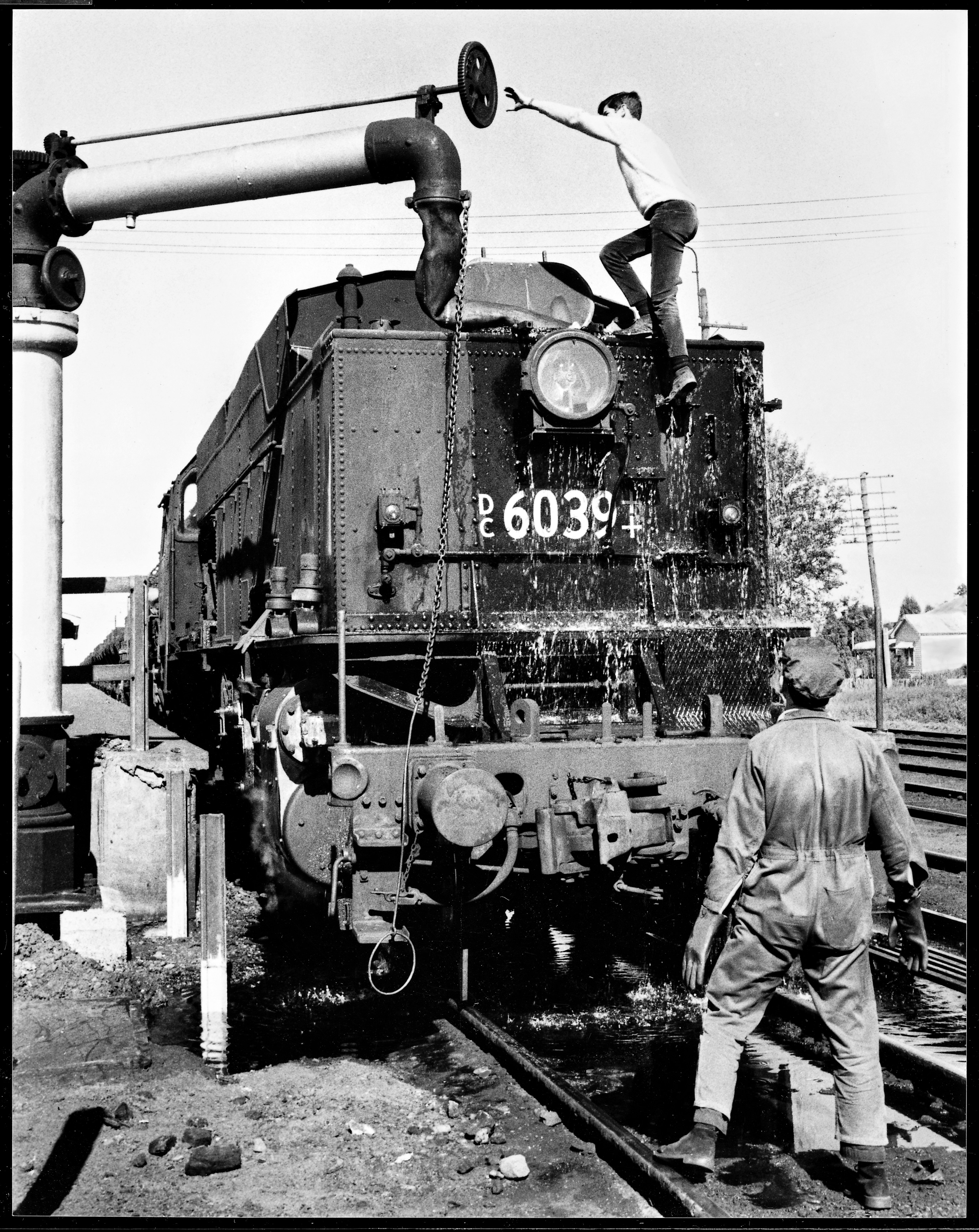

Back in the 1960s, a couple of teenage enthusiasts seemed to be instinctively aware that people were an integral part of the story of the steam locomotive and began including them in their photographs… drivers, firemen, guards, engineers and stationmasters. In the process, they started taking very different photographs from the standard three-quarter view of a locomotive and its train of goods wagons or passenger carriages.

Again, their feel for framing, composition, viewpoint and exactly the right moment to press the shutter also appears to be instinctive as, at 13 and 16 years of age, neither had had any photographic training. Yet today, those photographs taken over 50 years ago exhibit a remarkable maturity of vision and interpretation. What’s more, they didn’t just fluke the occasional great photograph, but the whole archive is full of them and enough to have yielded, so far, five books, with a sixth on the way and possibly another two to come. A couple of teenagers! And, at the start, with just a simple Kodak Brownie box camera that they took turns using!

Railway culture

In May 1963, Robert Wheatley and his younger brother, Bruce, set out from their home in Western Sydney and, on their own, headed to Goulburn to photograph steam locomotives. This was a day trip, but the following September they convinced their mother to let them stay out overnight on an excursion to Junee.

The brothers soon decided that they needed more time for these photographic expeditions around the state of NSW and managed to convince their mother – by promising to send her a telegram every two days – that they’d be safe. They travelled by train and often slept in station waiting rooms, under the watchful eye of railway staff who, wherever the brothers went, were always accepting of a couple of itinerant teenage steam enthusiasts armed with a box camera.

By the mid-1960s, it was clear that steam would soon be finished in NSW and, in fact, it had already disappeared from many parts of the network. No doubt many of the people Rob and Bruce encountered – who had worked with steam engines all their lives – understood their desire to record what would soon pass into history.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

“When we started roaming the railway network,” says Robert. “We unwittingly began absorbing the railway culture. Immersion in this world shaped our photographic style. In those early days, I saw men working in a fusion of light, smoke and steam, and I was overwhelmed by the photographic opportunities. But my training in photography was limited to the booklet that came with the purchase of my first 35mm camera.

“Something happened between the very end of using the box Brownie and getting our first 35mm camera. We were no longer just content with a train going along the track. We started taking time exposures with the box Brownie, and then started to realise that taking anything that was moving with that camera was always destined for failure. The over-whelming desire soon became to get a 35mm camera, if we were really going to be able to capture the essence of the steam engine.

“So it was a really big event when I brought my Petri 7S camera. I’d saved up £32 – and at that time Dad was earning £17 a week – so it was a lot of money for a schoolboy. It was 12 months of working Saturdays, but I knew I needed a 35mm camera and I was prepared to wait for it. I knew nothing about cameras and Paxtons sold me the Petri without showing me anything else, but of all the cameras I’ve subsequently had, it turned out to be the best… lightweight but strong, a wide-angle lens with great depth-of-field, rangefinder focusing and just a breeze to use. Many of the more challenging photographs that we were able to take in the earlier years were because of that camera mainly because it was, for me, so forgiving.”

The Petri rangefinder camera was eventually joined by a Pentax Spotmatic 35mm SLR, although Rob recalls that they only ever used the standard 50mm lens, but now they had the luxury of two film cameras. Then in 1968 the brothers bought a Yashica-Mat 6x6cm TLR.

“It was all we could afford,” states Bruce. “But we really wanted to use medium format, although it took us a while to get used to it… especially the reduced depth-of-field. With the Petri, we’d been used to shooting pretty much everything with the lens set at infinity, but the Yashica needed more precise focusing, especially if we were shooting at f/4.0 or f/5.6. In the end, I don’t think we ever got the best out of it.

“We used Ilford FP4 and HP4 because we found they were more forgiving than Kodak’s B&W film and I also found them easier to process. To save money, we bought it in bulk rolls and then loaded our own cassettes in the darkroom.”

Focused determination

So what came first, steam trains or photography?

Bruce is emphatic, “It was trains for me. I can never remember a time that I wasn’t crazy about trains, right back to primary school”.

Robert contends, “Without photography, we wouldn’t have kept up our interest in trains and without trains we would never have become photographers. So trains forced us into photography – it was a by-product – but from then on the two went hand-in-hand and, for us, you couldn’t have one without the other.”

Starting out, the boys simply responded to what they saw with what Robert calls a “focused determination”, but both were complete novices as far as photography was concerned.

“We had no artistic background whatsoever and we didn’t have any prior associations with the railways either. So it was all 100% self-taught. It’s a bit of a mystery because, if it was just me by myself, you’d say it was my ability, but the fact that we’re identical… identical… in the way we see – so that you can’t tell Bruce’s photographs from mine – but we’re very different personalities, means it must somehow be genetic.”

They built a makeshift darkroom in their mother’s outside laundry and then every second Friday night for five years they processed film and made prints, the enlarger set up on the washing machine.

“It was chaotic,” Bruce recalls. “And cold…very cold”.

There was a school of thought among most train photographers – and it carried over into aviation too – that the best photograph was one that solely hero-ed the subject without any distracting clutter… and clutter included people. Almost from the very beginning, Robert Wheatley contends, he began thinking exactly the opposite, that having people in the picture added to it rather than detracted from it. The human element was actually a vital ingredient.

“When I was 15, I saw this English magazine and there was a photograph of a train driver coming off a turntable, rubbing his eye – getting a cinder out of his eye. There was a steam engine in the background, but this was an environmental portrait more than anything else, and I realized straightaway that these were the sort of pictures that I wanted to capture. I realized then that people were important.”

Bruce adds, “I was more a number collector to start with, and I just wanted to get a picture of say, 3814, but Rob would always want us to focus on the people. We did both, but I always found photographing people harder to do, and we often shot in difficult lighting situations where it was dark or there was strong backlighting… or you were on a 200-tonne engine moving at 60 miles an hour, it was very hot and you were continually getting covered in cinders and grease!”

Access all areas

If Robert and Bruce have their parents to thank for the freedoms they were allowed, it was also made possible by the accessibility to the rail network that was possible in the 1960s and the way the system in NSW was run.

“Different world back then,” states Robert simply. “It just wouldn’t be possible to do it today, because everybody is so risk averse now. But what we did could also happen because we were in Australia, and there was a much more relaxed attitude here than in say, Britain or Germany. We virtually had full access… we could just go into any depot, and sometimes we asked permission and sometimes we didn’t. That didn’t happen elsewhere… it was actually illegal in Britain to go onto railway property. There may well have been a rule somewhere here too, but the drivers took it upon themselves to allow a schoolboy up into the cab… that was the Australian character side of them.

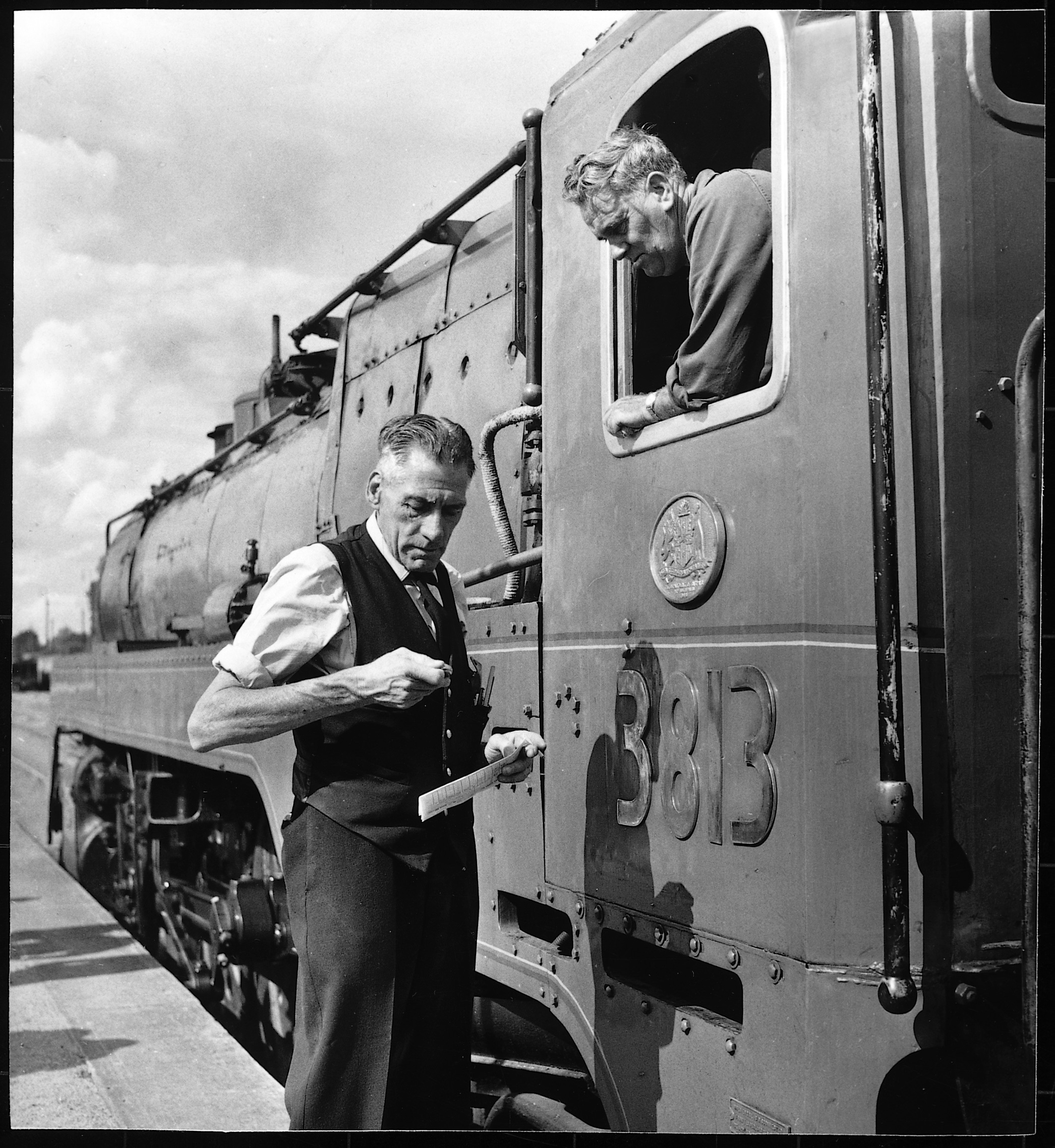

“In the railway hierarchy, the driver was right up there,” states Bruce. “Stationmasters had a bit of clout and guards had a little bit of clout, but the driver was the one that was ultimately responsible. And to a man, they were all characters, absolute characters.”

“They were like ships’ captains who, once they left port, they were in charge. While the train was in the station, the driver was subject to a rule book that was two inches thick, but once he had left the station, what he did in his cab was his business. So we soon learned that if we got with the crew then we’d be OK and we could do what we wanted. You never asked the fireman for a ride, you always had to ask the driver.”

Robert continues, “For school boys like us to approach tough men like that, it took every ounce of courage that we had. But our passion for photographing steam engines overcame our fears and, if you could eyeball a bloke like that, to our surprise, they were the friendliest and most accommodating people”.

Adds Bruce, “But they had to know that you at least knew ten percent of what they knew… mind you, that ten percent was still huge… they had to know that you were safe and weren’t going to do anything stupid. But the fact that you just got up into the cab, you were home… they knew you had some knowledge and awareness of how things worked. It still took a huge amount of courage though”.

Creatures of the night

It was something of a revelation when the boys discovered night photography.

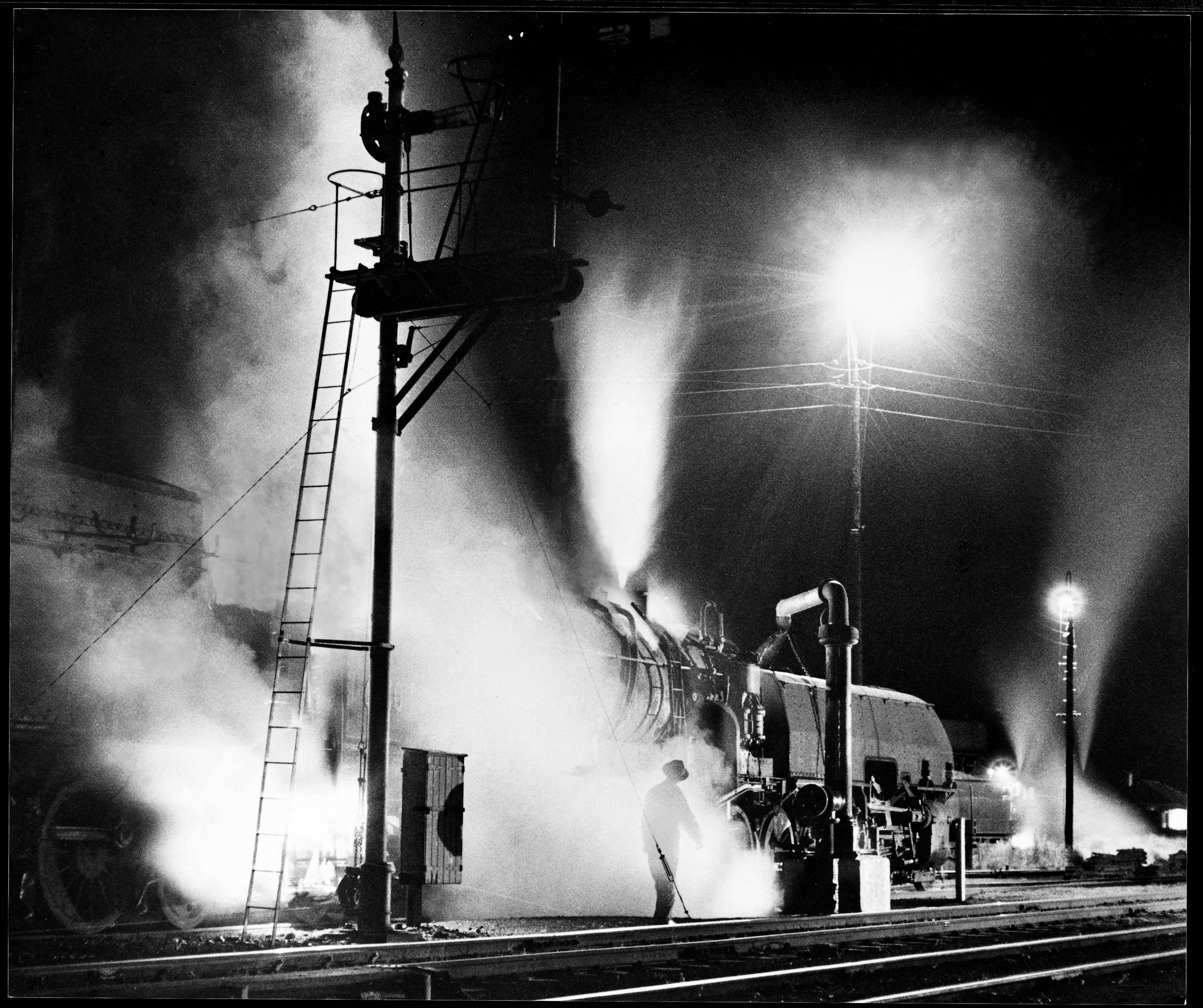

“When we first saw a night shot of train,” recalls Robert. “We were just stunned. We’d never thought it was possible to shoot at night, but within a couple of months we had it mastered. Actually, we enjoyed night photography so much that we would often set off at two o’clock in the morning just so that we could take photographs in that last two hours of night and then at sunrise. Photographing at night was a potent time because the steam engine was just so much more dynamic… the white steam against a black sky, the glow from the firebox. They really were creatures of the night.”

“We had to experiment a bit,” Bruce adds. “For example, most passenger trains didn’t stay in the station for more than two minutes so we quickly found that, at f/11, the exposure time was too long, so we started using f/5.6. And then a steam engine at rest isn’t always completely stationary, it might roll back a little bit. Flash would have been ideal for getting crisp steam, but then we soon learned that flashes alerted the whole railway yard that there was someone there. As time went on, I think the railways were started to lose their tolerance for rail fans crawling all over the place, and flash was a part of that. We were always conscious when we were letting off flash bulbs that it was potentially dangerous, but we mainly used them for fill-in.”

Delays with the dieselization of the regional railways in NSW kept steam alive in the state longer than would have otherwise been the case, but by 1967 the end was nigh, and so the Wheatley brothers’ rail-borne adventures were coming to an end too.

Robert explains, “What happened was that we had realized you could travel for free on goods trains – either in the brake van or in the engine cab – and you could get yourself to Lithgow, go to Dubbo, go to Cowra, go to Nyngan, go to Binnaway… all being hauled by a steam engine. You could sleep in the brake van and then wander around quite freely through the depots. This was how we got around for quite a few years”.

“It was the last division in NSW still with steam,” chimes in Bruce. “But once that went, it became very fragmented and we had to start traveling to places by car and, while it was convenient, it meant we were one step removed from the railway experience. In some ways, it was never as exciting after ’67.”

“When steam finished we went through a grieving process,” states Robert. “It was like this friend who we’d been watching gradually die over a period of 10 years. We’d gone from something like 700 steam engines down to the last half dozen.”

“You’d walk into a big depot like Bathurst,” Bruce recalls. “And there would be 50 or 60 steam engines lined up, all making some sort of noise and blowing smoke. You went into the same depot just a few years later after diesel had taken over and there’d just be these animated biscuit tins sitting there… it was completely soulless. Efficient – it was what had to happen – but soulless. It was hard to take.”

Over their years of roaming the rail network together, Robert and Bruce amassed an archive of over 20,000 B&W negatives.

“It was every second weekend and every school holidays,” says Robert. “But there were periods there when I’d go out shooting during the week, come back on the Friday and hand the camera over to Bruce to take out for weekend.

For the first few years we were always together, but then as we got older we did things separately for a while, but then at the end, we were together. This was when we became really specialised and had perfected the ‘art of the footplate’. I don’t think during those last couple of years we ever got a knock-back. By that stage we really knew how the railway mind worked.”

Into print

When steam finally finished in NSW in 1973, Rob moved onto other interests and Bruce tried to rally some enthusiasm for diesel locomotives, but the teenage adventures around NSW were over. The archive – along with Bruce’s meticulously kept records – lay largely untouched for decades.

“Eventually, I said to myself, we just cannot go year after year without doing something with our negatives,” explains Rob. “So I started looking at how we could get a book into print. At that stage, I thought we might be able to get one book or maybe two, but what has been a total surprise is just how big is our reservoir of photographs… and we still haven’t got anywhere near to the depth that we could go.”

“Well, in the end we were photographing so furiously that we just processed the film,” adds Bruce. “And many of these negs I’m only just starting to print now… so we’re still being surprised about what we’ve got.”

The brothers elected to self-publish, preferring to take the financial risk in order to have control over the editing, design and distribution. Once again, they’ve been travelling around NSW together, this time to sell their books at train fan events, rail modeller shows, shopping centres and even local markets. The first volume of Railway Portraits was published in 2006 and has since been reprinted six times. Work on the sixth volume has begun and, as with all of them, Bruce has been in his darkroom, making B&W prints that will be scanned to create the digital files.

“Well, eventually I did decide to start photographing diesels and so, from about 1977 onwards, I’ve just kept going, which meant I got back into the darkroom as well. I’ve now probably got more diesel shots than I have of steam, but… they just don’t have the excitement. Nothing could replace stream. The good thing though, is that I’ve kept my darkroom skills up.”

Rob states, “I have to say that self-publishing has really worked for us, not just in terms of being completely in charge of selecting the photographs and how they all go together, but also how we sell our books. A distributor simply wouldn’t put in the effort to go to all the events where books like these will sell, but we’re happy to do it… together we’re still a formidable team. But also the people who buy these books like to be able to talk to us directly… and we often meet friends and relatives of the people we photographed.”

“Of course, back then we weren’t thinking about photographing for the future,” says Bruce. “You don’t think like that when you’re that age. We were just having fun. But later on, when we realised how close steam was to ending, it became a lot more frantic and we knew we had to record it before it went. We didn’t have the luxury of tomorrow, so we became obsessed about photographing everything we could see and, in some ways, that’s when the adventure went out of it.”

All these years later, as they continue to discover hidden gems in their archive and with five successful volumes of Railway Portraits behind them, neither brother can precisely pinpoint how they’ve shared the same vision and, completely untrained, both had the intuitive eye of a seasoned street photographer.

Proffers Rob, “Well, I think that, after a year or two, we were totally immersed in it and we knew railways and railway men back to front. So we weren’t trying to photograph an idea, we were photographing whatever was happening in front of us, but we also understood what was happening and why. That was the difference.”

“You can’t photograph what you can’t see.”

Railway Portraits volumes one to five are available for purchase directly from Rob Wheatley. Email to robertwheatley@appt.net.au to enquire. Each volume is priced at AU$55, but there are discounts when buying multiple volumes.

Related articles:

Best film cameras available now

The rise and fall of the compact film camera

110 cameras: rise and fall of the film format that made photography easy

Best Lomography camera

Best film scanners

Best darkroom equipment

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.