Sharks on a plane! Cinematographer Andrew Rodger talks cult hit 'No Way Up'

Cinematographer of chart-topping movie 'No Way Up' talks the kit and technical approach behind the disaster-horror hit

After a worldwide rollout, the disaster and survival-horror movie No Way Up landed on Amazon Prime last week – and it spent the weekend holding the number one spot. And at the time of writing, the movie was still in the Prime top five.

I chatted to the movie's director of photography, Britain's Andrew Rodger, about the constraints of shooting in a submerged aircraft set, and how he helped director Claudio Fäh capture the action. So read on to discover the cameras, lenses and LEDs that he used to bring this shark-infested movie to life.

Oh, and beware of some movie spoilers as we chat about the challenges that Andrew faced when filming above and below the surface…

No Way Up is mostly set in the confines of a crashed plane's shark-infested cabin. How did you choose the camera gear to tackle the challenges of filming above and below the water in this slowly sinking set?

We shot No Way Up in 2022, before the new Alexa 35 came out, so we shot the whole thing on the Arri Alexa LF.

I really like the Alexa system. I've been using them on TV and film whenever I can – they're very predictable and robust and I knew that we'd be underwater and shaking them around and hanging out of helicopters, and I knew that the Alexa would be able to handle that. In the factory when they they build an Alexa, they put it in a paint can shaker and they just shake it about – and then if it doesn't fall apart, it passes!

It's just as well – I've seen behind-the-scenes footage of you shaking the camera during the plane crash sequence.

Often when you make big-budget action movies the plane set sits on a gimbal that can spin around on robotic arms. However, we just didn't have the budget so we explored all sorts of ways of shaking the camera to get that turbulence effect.

If you attach a drill to the camera with an off-center bit, you’re going be have to fight against it. But I wanted to be able to keep the dialogue during the plane crash; if you've got a noisy drill running then it just ruins all the sound.

What rig did you use to get the camera to mimic the crashing plane’s turbulence? A cage?

The rig was me! (Laughs). No cage. I think it was just moose bars! I do a lot of handheld work when I can and I like the camera to be as small and as light as possible. The Alexa LF is quite a small camera so we just shook the cameras! These Alexas were were fantastic. There was never a problem – no boards fell out and no lenses came off.

What lenses did you use to film in such a compact set? I didn't notice the type of edge lens distortion that you'd expect to see when using a wide-angle.

One of the first things that Altitude Films said was, "We want it to be anamorphic." It has to have this kind of Eighties / Nineties action movie feel, and I love that period of cinema – that's a big influence for me. So the lenses we used were called Caldwell Chameleons.

I think that at the time there were only ten sets of these in the world, but they're these full-frame anamorphic lenses. If you hit anamorphic lenses like the Chameleons with a strong light they will flare with a kind of Panavision-style horizontal blue flare. Which is quite exciting!

Another good thing about the Chameleons is that they're all the same length and same weight I think as well. So when you're going between gimbals, steadicams and underwater housings, there's no need to rebalance the camera.

When you're on a film set or big commercial you've got your camera and all these add-ons, such as remote follow focus units and video senders, so you end up with this big mass of cables. So having something that didn't change saved a lot of time and it helped us get more shots.

Anamorphic lenses can be difficult as well, because anamorphic lenses don't often don't focus very closely. You have to be a couple of meters away from the subject for it to focus, but often I was three feet from the actors and as you say – if it's a wide-angle lens you get all this distortion and people don't look good.

So shooting full frame helped because it meant the lenses I was using didn't have to be as wide because the gate – the chip – was bigger, so everything is more rectilinear. Everything is straight, there's no barrel distortion.

What were the logistics of getting your gear, film crew and actors into a semi-submerged aircraft set?

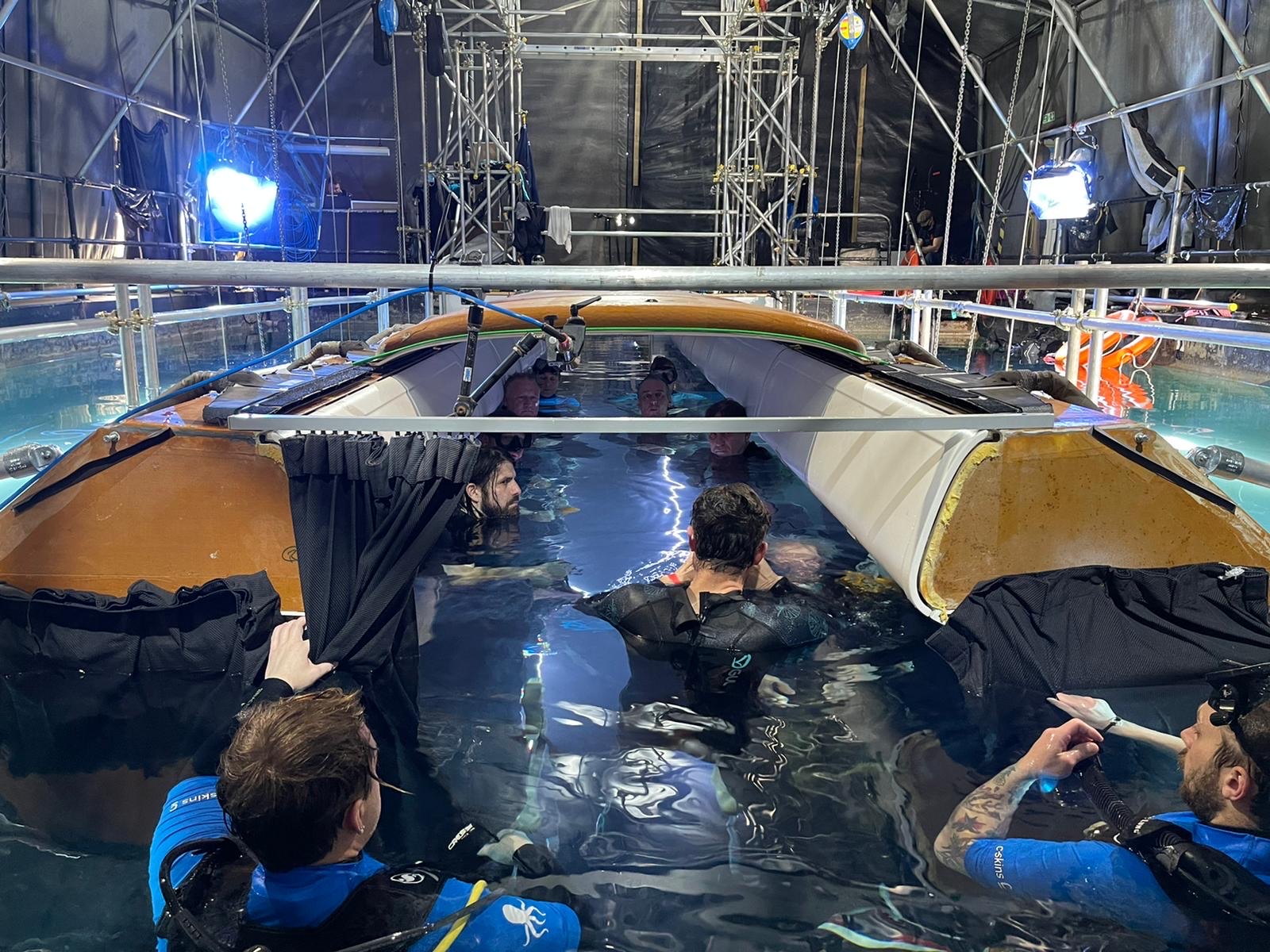

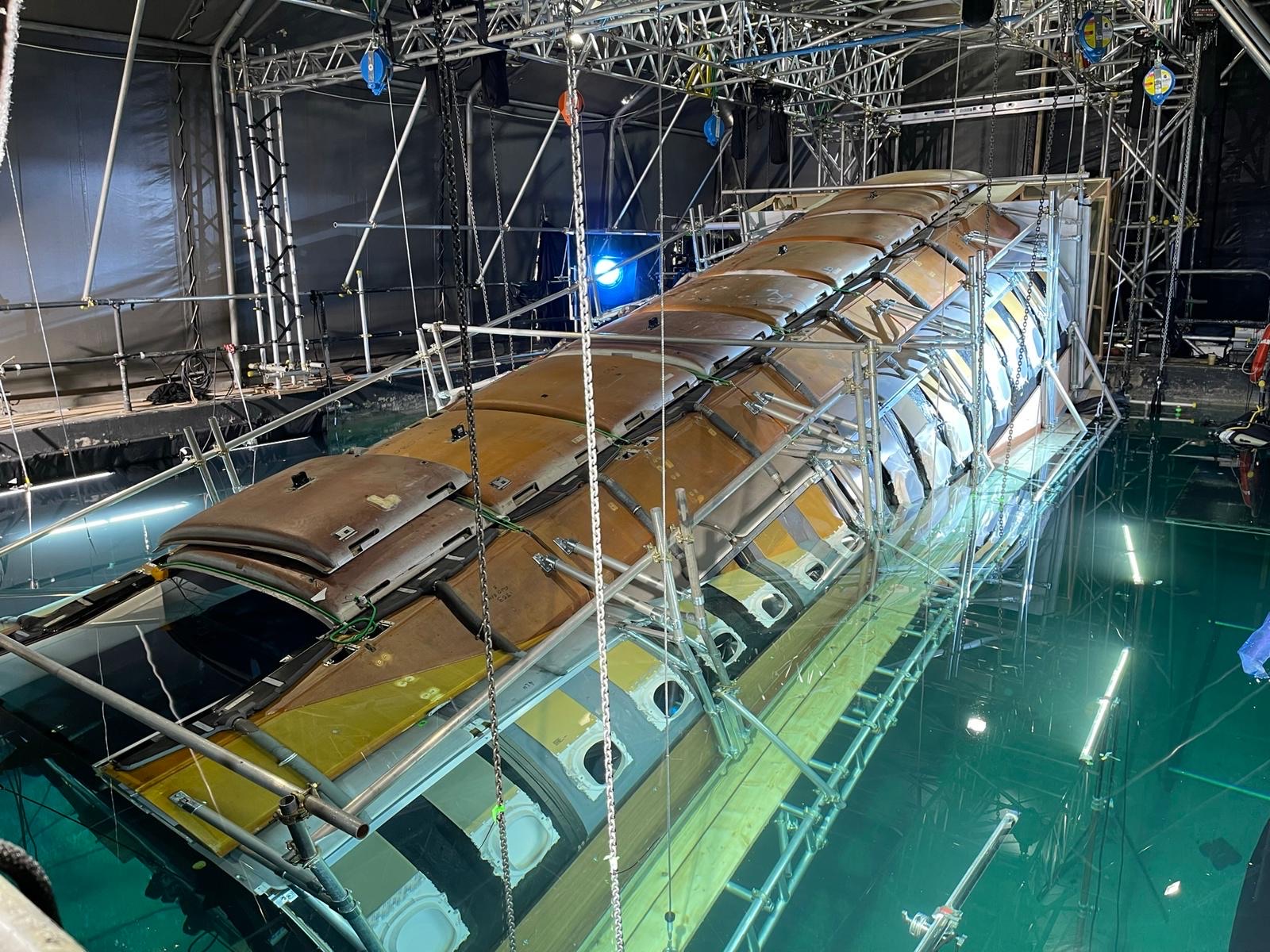

There are two main sets used in the film. There's a dry set, which was the set built in a warehouse on a platform for the airplane, and then a different wet set dipped into a big water tank, so I'm able to dip the camera just below the surface.

As the cinematographer I'd have to get into the wet set first, the sound would get in, then all the cast would get in and then they'd lower the airplane set into the water. This took ten minutes, so if I had to change something it would be "Everyone out!", So it was important to be able to have a lens and camera setup that would just work for whatever I needed.

How did you protect your valuable camera gear from the water?

That was done in a thing called a 'dive bag’. It's basically a big bubble but on the side of it is a little fan that exchanges the hot air for cold air, so the front of it is glass and then behind it is just a big plastic bubble.

We also used quite a few gimbals in the movie. We used a traditional Steadicam in the airport section and we used a DJI Ronin gimbal on the airplane. My gimbal and Steadicam operator is a guy called Nathan O'Kelly, or if I need a drone he's the guy.

Let's talk lighting – how did you go about the challenge of lighting a semi-submerged aircraft cabin set?

This is kind of a horror movie; it's an action movie and there are sharks, so it needed to have a mood and be a bit scary. And light obviously plays a huge part in that. There's also a race against time in the movie, so the lighting changes. Because the plane's not that deep underwater, there's light from the surface coming in – so you've got daylight and then later moonlight.

Then there are the red lights on the wings of the airplane that come in later. I love red light in films, I think it heightens things. We were going for that kind of Eighties feel as well – sometimes you want that kind of emotional realism in a film. That particular lighting might not actually happen, but I wanted that feel. So below the surface are basically PavoTubes.

I've reviewed PavoTubes for this site. Are they waterproof?

They are "water-proofed"! So Bernie Prentice, my gaffer, had a load of these units made up, and they're basically within waterproof tubes. Then above the surface, we had Nanlites on the land next to the water tank. Those lights were shooting in through the plane's windows to provide all the sunlight and moonlight.

In the movie whenever you look towards the [shark-infested] water it's the underwater set. When you look up towards the galley [where the survivors were huddled], the galley isn't there – that’s back on a separate dry set. So we had to match the lighting to make both sets look like they were in the same location. Plus a lot of that was down to the grade.

It was so convincing. Everything looked like it was shot on a single set!

All the lights were on an iPad control unit, so you could dim them up and down, and there was a lighting desk as well for some of it, so it meant that we could dynamically change the lighting. As the plane was sinking deeper we could dim things on the desk and on the iPad so that it felt like it was getting darker.

The only thing in the airplane that was a lighting source were these two domestic waterproof emergency strips down the center. They were RGB, so you could change the color; 80% of the lights came from those strips in most of the underwater scenes.

Do you have any memorable highlights of filming in the wet set?

At the end of the movie, the plane fills completely with water. And the way to do that is to sink the thing on this big rig. So I was getting pushed underneath the luggage compartments, because I was sitting in the seats with my camera, so I had to have a diving regulator. I'd start the shot above water and then by the end of it I was completely underwater to film the actors swimming out. I must have done it 10 or 15 times in a couple of days, so that was a lot of fun.

It was quite stressful and there were a lot of moving parts, but it's a big team so you can rely on people. There was a safety diving team. So we shot the escape sequence underwater. Then as a backup, we ended up using this virtual production stuff – the kind of kit they use on The Mandalorian. It's an absolutely vast LED screen.

Ah yes, they use those huge LED screens on Doctor Who, too. And as a bonus, you get interactive lighting from those screens on the actors.

You do get light off the screens, and that's part of their selling point. But you can't use the light off it because the screens don't have a high CRI [color rendering index] like an LED light would have. [Andrew gestures to the Hobolite Mini that I'm using to film the interview, which has a CRI of 96 out of 100.]

So the light quality emitted by a virtual production LED screen is not faithful, you don't get good skin tones out of it. So you still have to light around it. But you do get reflections and things off it.

So the virtual screen meant that you could shoot underwater scenes in the dry?

Yeah. It meant we were able to do the shot of Eva [actress Sophie McIntosh] swimming up from the completely submerged plane. Normally this would be a ‘"breath hold" underwater, which we just couldn't do. And she had to drown on camera and we didn't want to drown her, so that was done "dry for wet" with smoke and backlight and these LED screens to mimic an underwater environment.

How did you get the shots of clouds through the windows before the plane suffered a bird strike? Were those sky elements composited in?

So normally if you're going to shoot an airplane, you put a green screen outside the windows and every shot becomes a visual effects composite. But there just wasn't the budget to do that – there would have been 150 VFX shots. So, it's quite low tech actually, we did front projection, which is a Stanley Kubrick 2001 thing.

We had four projectors down the side of the airplane. Attached to absolutely vast scaffold towers built the length of the plane was a 20-foot-high screen made of ultra bounce – which is a reflective material stretched across both sides of the plane like a vast long tablecloth. And then we front-projected footage of clouds going past onto that [which could be seen from any angle inside the plane set].

The movie seems to have been released everywhere else before reaching the UK where you live. How do you feel about turning on Amazon Prime and seeing it debut at number one?

It's lovely! We shot this film a couple of years ago – it's always the way with these things that they come out later. But it's done a US cinema run, the Middle East, all over the world. So for it to come here and then be on streaming – because everyone's been asking me for the last year or two, "When's it coming out?" – for them to turn on Prime and see it on the first page at number one, it's lovely!

You might be interested in the best cameras for filmmaking, and don't forget to investigate the best cine lenses for filmmakers.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

George has been freelancing as a photo fixing and creative tutorial writer since 2002, working for award winning titles such as Digital Camera, PhotoPlus, N-Photo and Practical Photoshop. He's expert in communicating the ins and outs of Photoshop and Lightroom, as well as producing video production tutorials on Final Cut Pro and iMovie for magazines such as iCreate and Mac Format. He also produces regular and exclusive Photoshop CC tutorials for his YouTube channel.