Steven Berkoff: “I have pics that are worthy of Cartier-Bresson”

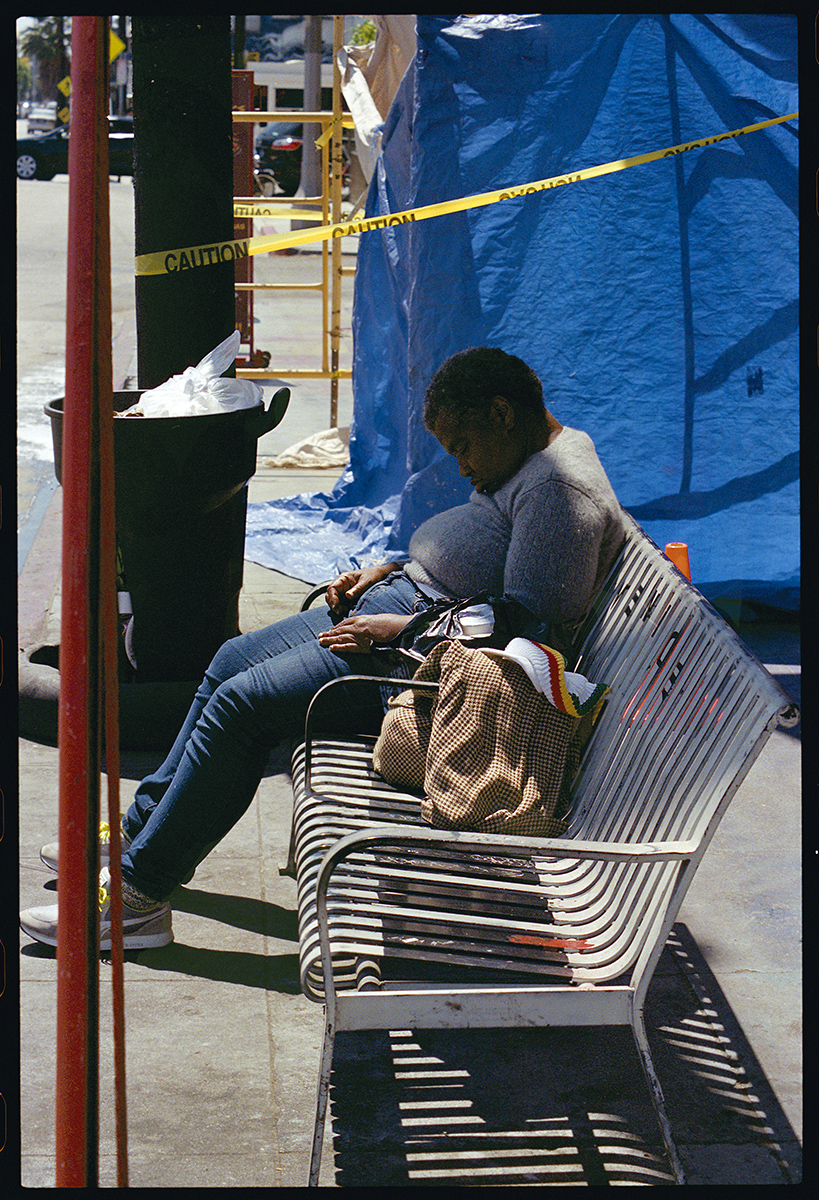

Renowned actor discusses his new exhibition, ‘Homeless in Hollywood’, at the Wex Photo Video Gallery in London

Steven Berkoff is known the world over for his performances on the screen and stage. From early roles in British television shows like The Avengers and The Saint, to his notable turns as a Bond villain in Octopussy and the corrupt art dealer in Beverly Hills Cop, to his controversial plays like Sink the Belgrano! and Harvey (based on Harvey Weinstein), in which he often serves as writer, director and actor, he commands a reputation for dealing with subjects that are rough, raw and real.

A lifelong student of photography, Berkoff’s gift for storytelling extends behind the camera. An exhibition of his latest work, ‘Homeless in Hollywood’, has just opened at the Wex Photo Video Gallery on London’s Commercial Road, which runs until 15 April 2019 with free entry.

The collection of 40 images, shot on his Rolleiflex camera, depicts the contrasting lives of the homeless population living behind the glamorous backdrop of Hollywood. The photographs are accompanied by a documentary shot by the actor, Venice Beach, in which he converses with many of the subjects featured in the gallery.

We met with Berkoff to discuss his work, his approach to photography, shooting on a Pentax vs a Rolleifliex, performing Shakespeare and Kafka, and the perils of staging a new play about Harvey Weinstein…

Digital Camera World: You shot these images at California’s Venice Beach. What was it about Venice, specifically? It’s a real melting pot there.

Steven Berkoff: Yes, that’s a good expression. What attracted me to it, because it’s very raw, and almost a bit subversive. It’s weird, it’s for the outsider, the renegade – and it attracts those types of people. It also attracts people in the creative arts, like filmmakers, musicians. So it’s kind of a cultural enclave of LA. And I used to live on Venice Beach for a while – I liked that area, because it was the first area I got to know when I came to LA.

When I first went in the Eighties, it was totally crazy street theatre. There were the most extraordinary manifestations of physical art I’ve ever seen in my life – mime, breakdance, acrobatics, yoga – amazing things. Everybody rollerblading, doing marvellous tricks, and wonderful mime artists, they were beautiful. And street comedians doing the most amazing kinds of inventions. So I was fascinated.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

And then, when they went in the evening, there were left all the beggars, and all the down-and-outs, and the druggies and the alkies. And in the morning when I got up they were there, of course – they couldn’t sleep on the beach, it was against the law, so they slept in alleyways, car parks, the back of hotels, anywhere they could find a spot. And I got attracted to these weird, wonderful people. And I wanted to talk to them, find out how did they get there, what their lives were.

And there was a reason for wanting to talk to them: because they had faces that were raw, real, definite, naked. Unlike the usual kind of middle-class, plastic, yellow, shaped-faces that normally cruise up and down looking for a bit of ‘fun’, and they go to Venice and say, “Oh, look at him, look at her,” as they look at all the mads and the nasties. So I was rather fascinated by them, because you see them and you’re drawn to them, to the feeling on their faces, which was the feeling of soul. Which is only revealed under enormous stress and degradation and drugs.

"It was totally crazy street theatre. There were the most extraordinary manifestations of physical art I’ve ever seen"

Steven Berkoff

So then one day I said to my friend, “I want to make a documentary. Have you got a video camera?” And he said, “Yeah, I’ve got one actually.” So he came down, and then I felt empowered by the camera. I could go up to people and say, “Can I take a pic, a video of you when you’re talking? You’ve got a very interesting face. You’ve got some character, mister.” And they say, “Hey, thanks.” And you say, “How long have you been here?” And they start talking.

As the camera is rolling, I find that they’re revealing themselves, some of them talking for the first time in maybe weeks. They started to reveal their hopes, their passions, their desires and frustrations, and I talked and we made a video, over three days, called Venice Beach. At the same time, I started taking still shots, just where I saw them. I took shots of most of these people, and then I got to know them, and became more familiar.

And then I had them all blown up. And I was here [at the Wex store in London] one day looking for something, and I said I’ve got some photographs and they said, we’re trying to establish this as an exhibition centre. And that’s it – that’s the story.

To ask, or not to ask?

When photographing these subjects, what was more interesting to you – was it more interesting to approach someone with your camera, and ask if you could photograph them, or to get them ‘just being them’, unconscious of you?

Well, I did a bit of both. And that’s the sneaky way [pantomimes shooting his camera from the waist]. But I found they saw you taking a pic and sometimes they’d get a bit angry, that they’re being used. So I’d rather talk to them, I’d rather set up a conversation. I’d rather reveal myself, and then as they talk to me, they forget the camera’s there, and I can just snap away. And I find that if you talk first, and establish a relationship, and they get to know you, and then after a while they get to even like you. And then they wave, and they say, “How you doing, pal?” And I say, “Great! Here’s a few bucks.” I was like adopting them, if you like!

So I got to know where they came from, how long they’d been there, how one of the guys was in the Navy and dropped out, and they gave him no compensation or pension, and then he ended up on the street because he lost his flat, and his wife divorced him. And gradually in America there are less and less safeguards, less nets, to prevent people crashing. There are so few of them – they fall, and once they’re down on the street, and they can’t get unemployment [benefit] unless they’ve been in employment, and it’s hard for them to get a place to live, and they end up eventually begging on the street.

And some cities it’s more than others, some places it’s like plague proportions – like Skid Row, LA, people are frightened even to go round there. So eventually they get pushed more and more out of the cities, until they come to the beach – they can go no further. There’s the sea. At least there you don’t have to have log-ons, and passwords, and all the shite of our world. You just have the sea, a few cafes, you can beg a crust, the people get to know you and you can live. And the beach people, I found were to me so very interesting.

Venice is very much living theatre. You go there and the place is very much alive, and has a real spirit, but that spirit changes when the sun goes down.

Well at night it goes dead, you see. It’s funny – here, in Europe, at night all the cafes would open, and you know, the musicians would come out. But in America, night equals danger, especially at beach resorts. So they couldn’t cultivate the cafes to open till midnight and have musicians – that would be very pleasant, one or two might be able to open a bit later on the sidewalk. But I was always amazed that when it was dark, there was nobody attempting to enliven the place.

So I was doing that, taking pictures – I’ve always taken pics, and a long long time ago I did my first exhibition. I used to go down with my Pentax to the East End. And I would take pictures of the East End as it was crumbling, dying. So the people that had appealed to me to photograph were the old, the infirm, the decayed, the people like beggars, the sick, and maybe little stall holders selling bagels, women selling pickles in the East End. It became a very, very good exhibition, in black and white.

There’s a theme, there, that decay – human decay.

Yes, it’s human decay, it appeals to me. Poverty appeals to me. And it appeals to me in the sense that, as with any photographer or painter or writer, you are drawn to what you identify with. So I identify with the down-and-out, with the poor, with the derelict, with the people who are on the edge of society – they move me. I’m moved deeply by them.

And maybe because I was born in the East End, and the marketplaces were the fun, smelly, rancid, funky places to go – I’m always drawn to these people, because these people have no pretences. They have no attitude, and they don’t have any social accents, they’re just what they are. And that’s a privilege, that they speak to me, and I get to know them, and they get to become friends.

"I identify with the down-and-out, with the poor, with the derelict, with the people who are on the edge of society"

Steven Berkoff

There’s a picture of a black woman, I think she’s originally from Jamaica. And she was on the beach, with her little blanket, and all her half-drunk cans of stale orange juice and apple juice, and a few bits of food. And she was just there – she didn’t have a laptop, she didn’t have a computer, she just sat there. She didn’t have anybody talking to her, but she was cheerful.

She used to have a room downtown, and she had a computer, and of course she lost that. She had nothing. But she was so happy to talk, her face beamed, and I’ve got that on the documentary. She was so beautiful and charming, as they all were.

How much of your interest in these subjects was because of that humanity, which you experienced in the East End, and how much was your reaction to the facade of Hollywood, and craving real people?

I just felt that these were people that spoke to me. The other people I’ve been seeing for years, and they’re all much of a muchness, and I’ve never taken one picture, except maybe of my agent, or a friend, from the LA community. Not one. Because they all look alike, they sound alike, they think alike, they act alike, their worries are alike, their concerns are alike, their ambitions are alike and their tastes are alike, so I didn’t really notice them. I didn’t notice them at all.

You mentioned that you shot on a Pentax for a while. Which one was that?

I don’t know – I used to always carry a Rollei. Because then you can take pictures secretly [pantomimes shooting from the waist again]. As you’re talking you’ve got the picture there, so you can say to them, “Oh, yeah! Really?” Then *ch-chick!* It’s a wonderful secret! Some of my old black-and-whites I took are wonderful.

Then I was abroad in Israel, and a photographer Gered Mancowitz – he was the son of Wolf Mancowitz [a fellow writer from the East End] – and he wanted to swap. He said, “You should have a 35mm, I’ve got two or three, do you want to swap?” And I said yeah, okay, it would be interesting to have a camera you did this with [pantomimes holding a camera to his eye, smiling and snapping away], you feel like a real photographer! So I bought that when I was in Israel, and I took lots of pictures. But I’m not a photographer, I’m a part-time actor.

Well, you're a storyteller. As a storyteller, what is unique to you about a photograph, as opposed to the ways you express yourself as an actor, or through writing your plays?

I don’t see any difference. You’re telling a story, you know, of rough people, unusual people, idiosyncratic people, original people, maverick people, dynamic people, poor people, sick people, deprived people, drugged people – all the people who are swept up in the torrent of humanity when it’s kind of in turmoil.

So that’s why I did a play last week on Harvey Weinstein. Interesting, fascinating subject. As an actor, you look all the time for people who you can express with your particular vision and abilities or opinions. When I was young I wanted to play Hamlet, because I didn’t know very much, I thought it was an interesting character. And then, as I got older, I found other people – I wanted to play Macbeth, which I did. And then on to play Coriolanus because I directed it, and the actor doing it was fucking awful so I took it over and I played and directed Coriolanus, because he’s interesting.

So you pick someone who might be interesting, fascinating to play. And that because, as an actor, you are eventually a collector, like a stamp collector. You’ve got all these personalities – they’re like little demons, writhing around inside you, all these eenie weenie demons – and then you read something. “Oh, I want to play that!” You see an article. “I want to play that!”

And I read Franz Kafka, The Metamorphis – oh, that beetle! I wanted to be the beetle, I am the beetle, I am crushed, I am suffused with sense of terrible craving, and inferiority, and modesty and shyness. And the beetle, this small thing, is crushed, oh god, it’s terrible! And so I want to play him, I want to bring him to life. So, I wrote an adaptation, and then eventually I did play it, a few years ago in the Roundhouse originally, which I directed and performed.

And then the play got to be known, and I eventually took it around the world. I directed it in at least 12 countries, most notably in Paris, with Roman Polanski playing the beetle, in New York with Misha Baryshnikov playing the beetle, in LA with the late Brad Davis playing the beetle, and then I did it in Japan with a very good actor there, then I did it in Israel – so I’ve done it all over the world.

So that’s what happens, you find some character that appeals to you. My mind was exotic, it was suffused with the cells of my Eastern European and Russian background. I was only a second-generation Russian and Romanian, but many people from there did adapt to England and wrote good old English plays – Tom Stoppard and Arnold Wesker came from that background, partly.

Your play East was revived last year, and it was very well received. With the current political climate, what else of your work do you think particularly resonates now?

Oh, they all resonate now, I would say, because they’re not typical – they’re not just for the moment, they resonate through the years, I hope. But that’s why I did Harvey, I thought this felt just right, and I did it, and I got two reviews – I didn’t ask for reviews to come, because it was a work in progress, it was a tryout – but sneakily they came in to destroy me. And they were nasty reviews which bore no relationship whatsoever to what I did. None. Because the performance, and the show, was quite exciting – awesome, in fact. And they wrote “boring” – the bitches, the reviewers – they said, “Oh I don’t know why we can’t have a woman writing about what happened to her, and this is boring.” And she was lying! And that was disgraceful.

Batteries that last a year

Tell us about your relationship with your Rollei – why the Rolleiflex? It’s a very unique device, photographically.

Just to me at the time, I didn’t analyse it that deeply, just to me it was rated as a very high, beautifully crafted camera. A highly technical camera, with a very beautiful lens. I don’t know the difference between one camera and another, and I don’t know anything about digital cameras except, when you have it, you see the picture very clearly, and then an hour later the battery’s gone. So I thought, what the fuck is going on here? My battery lasts for a year! So then you’ve got to get another battery, you’ve got to know all about the different configurations and then, all the funny names – what do you call it, the stick? You put all the pictures on a stick!

I’m too old now to learn anything. And I think I like the Rolleiflex because the negatives are large. Then you put them into the enlarger, you have a large negative. And when you really blow it up you don’t lose any, could you say ‘pixel erosion’? More sharpness. So I like that, but you can only take 12 pics. And then eventually someone stole it, so I just stayed with my Pentax and Nikons. I enjoy the Nikons with a big telephoto lens, even though you get a bit of camera shake with a 200 or 300mm lens. But I loved that.

"As an actor, you are eventually a collector. You’ve got all these personalities – they’re like little demons, writhing around inside you"

Steven Berkoff

And then I started taking pictures of actors. When I started, I got to know about printing. Somebody gave me an enlarger, my brother-in-law, and then I started to learn, and that was quite amazing to me, that I could learn and then eventually become a photographer. When I became an actor, during periods of slowness, I would take pics of fellow actors for a few pounds, five or ten pounds, give them six 10x8s, so I’ve got loads and loads of pictures of actors. I enjoyed doing that.

They all were wonderful to photograph, they all had their stories, and one or two are now famous – there was Lynda La Plante, who’s a famous TV writer, I have a picture of her in her twenties looking really attractive. All sorts of people – but I don’t have any standout pics. I do have standout pics from the East End. I have pics that are worthy of – who was that famous French photographer?

Henri Cartier-Bresson?

Yes! Someone like Cartier-Bresson. I have a pic of a woman in a poultry shop, and she’s got all kinds of gore on her hands. And she’s sitting with her husband, and she says, “No, don’t take my picture! But take a picture of, I’ve got this photograph of my wedding.” And she pulls out of her bag this crumbling photograph, all creased, and she says, “Can you take it so that we get rid of all the creases?” Well, that’s funny, because when I was younger I thought if you took a photograph of a photograph that had creases in it, the photograph you’d taken would be without creases. I don’t know why I thought that! But she thought that too.

So I said okay, and she takes out this picture. And I’ve got my Rolleiflex and she’s saying, “Don’t take me!” and I said no, no. But her head was there, and my camera was slightly tilted, and she was holding the picture. You saw her face, the older woman – gnarled, with a scarf wrapped round her head, dark glasses on – and the young woman, beautiful with her wedding costume on, and her husband looking dapper. So I’ve got this, and her in the same picture – that to me is the most beautiful picture I’ve ever taken, in my entire life. And I adore that, and that’s a Cartier-Bresson picture.

People often say a photograph tells as much about the photographer as the person being photographed. What do you feel that your images say about you, as a person, as a photographer, as a human being?

I would like to think as a person who is, first of all, a humanist. That is revealing the sores and wounds of the unloved, of the poor and the destitute. Maybe he has a compassion for that, and that no matter what they say about me – that I’m this, that or the other – that would be foremost. And photographing, in a way, the world where it is most twisted; the world where it is most stretched and torn, that I’d photograph that.

But that’s no different to war photographers, but their objective is to really get compelling photographs of violence for the newspapers. So their objective is maybe a little bit tainted, because they really want to get bloody, but very powerful pictures. And they’re very courageous people. So I’m not interested, I wouldn’t like to go out, and looking for the wounded, and the maimed – I couldn’t do that.

What to shoot next?

Finally, if you could photograph any subject – living, dead, famous, infamous, actor, destitute – who would that be, and why?

Well this is a funny question because I’ve no idea. That I would not know. But I’ll tell you something: I saw some photographs taken in the Warsaw Ghetto. One set was taken by a Jewish photographer with a concealed camera – and they’re remarkable. But then this other set was taken by these two German, Nazi soldiers. I think the purpose was to show how filthy and disgusting the Jews were, and how they kept themselves derelict, filthy, gross, unwashed, because they were in the Ghetto.

They were starved, so it was a deliberate act of attrition on a most phenomenal scale. They had the Ghetto walled up, no one could get out. Over a period of time they brought in other Jews from all over Poland, so it was convenient to have them all in Warsaw. So during that time they were held in this awful condition, but the few had a little bit of money that they saved, and to cheer themselves up they would go into a little dance pot. And they [the soldiers] took pictures of them dancing – to show, look at these decadent Jews.

And then outside some of the cake shops were little children. And these little children couldn’t afford the cake, and most people couldn’t afford to give them a penny, so they just lay there waiting for the penny. And these kids all had sores, and bandages, and were dying. And if I had a camera, then, I might be tempted to go and photograph that.

That would be horrific, though. And it sound ghoulish, but it’s not; I would just find that compelling to record it, so that you made the world aware. Not because of any saintliness in me, and I don’t have a messianic complex. But when I find it compelling to see them and be with them, and somehow to, in some small way, to give some acknowledgement. And by doing that, to give them some interior nourishment, and make them feel… well, a hell of a lot better than they did.

Steven Berkoff’s ‘Homeless in Hollywood’ exhibition runs until 15 April 2019 at the Wex Photo Gallery, 37-39 Commercial Road, London, E1 1LF (nearest Tube station Aldgate East), with free admission.

Read more:

Famous photographers: 25 celebrities who also take pictures

Rolleiflex makes a comeback with the Rollei Instant Kamera

Best film: our picks of the best 35mm film, roll film, and sheet film for your camera

James has 25 years experience as a journalist, serving as the head of Digital Camera World for 7 of them. He started working in the photography industry in 2014, product testing and shooting ad campaigns for Olympus, as well as clients like Aston Martin Racing, Elinchrom and L'Oréal. An Olympus / OM System, Canon and Hasselblad shooter, he has a wealth of knowledge on cameras of all makes – and he loves instant cameras, too.