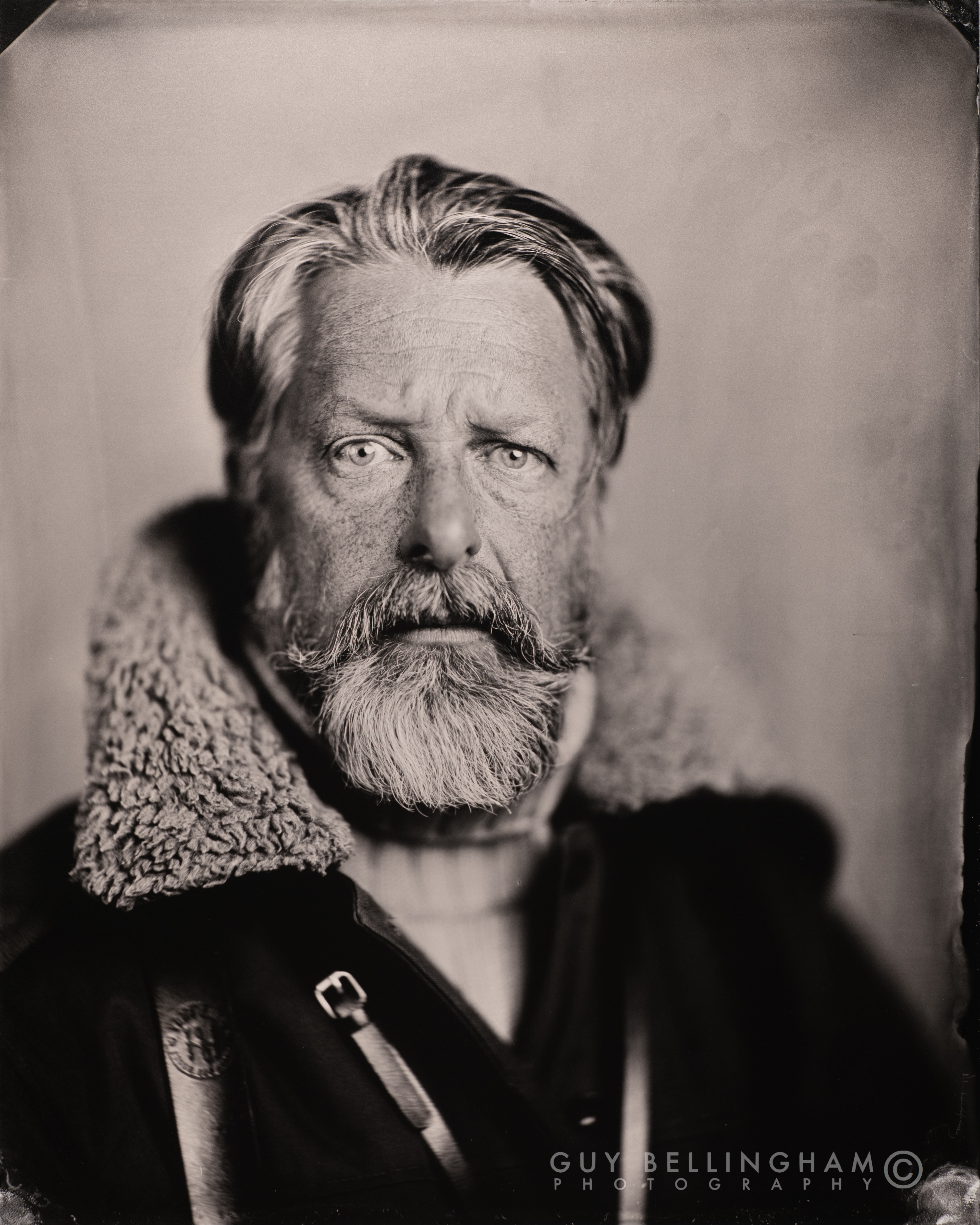

The art of tintype photography with Guy Bellingham – I got my portrait taken!

Tintype photographer Guy Bellingham uses this old-fashioned method to create beautifully eerie portraits

Tintype photography is one of the very earliest forms of taking photographs, dating from the 1850s. It requires precise chemistry, accurate timing and a traditional large format camera. Despite being a lover of photography, I’ve only recently come to understand the process and how much work it entails thanks to Guy Bellingham (FRPS) – a Bristol-based portrait photographer specializing in the wet plate collodion process.

For the last two years, Guy has been perfecting the technique that is by no means easy. I was lucky enough to be invited to his studio to have my portrait taken and be shown the steps from start to finish.

• Read more: Best retro cameras

As you enter Guy’s studio, you’re transported back to a different era. A vintage wooden radio sits upon a cabinet playing 1930s jazz, a floral chaise longue is tucked away in the corner, half-hidden by a dark backdrop, and on the opposite side a green, leather wingback chair sits next to a stool resembling an elephant’s foot. Of course, the main attraction of the room is the self-built large format camera that Guy uses to take his tintype portraits.

It took Guy several months to complete the camera build as sourcing parts, lenses and an adjustable Victorian studio stand for it to sit on wasn’t easy. This labor of love isn’t an overnight process, but a practice that requires dedication, perseverance and practice.

"The hardest thing was sourcing the lenses. As collodion is so incredibly insensitive compared to film or digital, you need huge, fast, large format lenses. To truly get the accurate Victorian look, you need a petzval design lens, with its characteristic field curvature and bokeh. For work on 8x10 plates, the lenses are huge, about the size of a large can of paint. They are neither cheap or easy to find as they are all antique."

Now that Guy has his setup locked down, the first step in the process is preparing your plate, which he does in his home darkroom – basically a converted hallway cupboard. Guy uses aluminum plates in either 4x5 or 8x10 inches, which he evenly coats in a collodion solution using a technique he has clearly mastered. The excess is carefully poured back into the bottle as he explains how much harder it is to get hold of the chemicals since Brexit (the United Kingdom's departure from the European Union).

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

“I do all the chemistry myself except making the collodion solution, which I have mixed up especially for me by a photographic wizard in Wales. He’s recently dropped off a batch, so this is pretty fresh, and I’ve taken his portrait too.” The particular solution Guy uses is called Old Dead Bride and is made up of a heady cocktail of cellulose nitrate, ether, alcohol, cadmium bromide and potassium iodide.

Once the plate has been coated, it’s time to put it in a bath of silver nitrate for three minutes. This is the process that makes the plate light-sensitive so, when it’s time to come out, the red darkroom light is switched on and all other lights are turned off, so that the plate can be wiped and placed into the plate holder.

The depth of field with this type of equipment is so incredibly shallow that it’s crucial to get the focus just right. The focus is set by adjusting the position of the lens thanks to the moveable bellows. The subject (in this case, me) needs to sit perfectly still while the photographer adjusts the focus. As someone who likes to fidget, it’s not as easy as it sounds – but just like the Victorians did, Guy uses a posing stand to help keep his subject’s head perfectly still.

Once the focus has been set, checked and Guy is happy, it’s time to insert the plate and get ready to take the photo. The lens cap remains on the lens, right up until the moment the image is taken. As the collodion has an ISO of around 1 the flash needs to be incredibly powerful, so that the image is bright enough, and it’s the flash firing that creates the exposure.

The plate needs to be processed immediately, so it’s back to the darkroom to coat it in developer that produces an underexposed negative. Judging by eye when it’s time to wash off the developer, fresh water is poured on the plate before transferring it to a tray of sodium thiosulfate fixer.

This is when the magic really happens. It takes about a minute to a minute and a half for the image to transform from negative to positive, and you can watch it take form right in front of your eyes. The end result is a beautiful, imperfect tintype where the areas of dark and light contrast immensely. There are only about five stops of dynamic range and collodion’s narrow spectral sensitivity creates a uniquely ethereal rendering; even light hair appears dark, and blue eyes really pop.

Although Guy also works using digital cameras, he’s clearly very passionate about this antiquated technique. “What’s really special about this process is that you’re actually creating a unique object, a one-off, an irreproducible portrait made of pure silver that will last for generations.

"I love how everything is done by hand and, unlike digital photography, you’re actually producing something precious and tangible that you can hold in your hands. Some say that when seen in the flesh, these plates have an aura about them. It really does feel like you are capturing people’s souls and immortalizing them.”

Watching Guy work really took me back to the roots of photography and while it was an incredible process to watch and be part of, it reminded me how fortunate we are that imaging technology has advanced so much. Picking up a digital camera and taking a photo might give you instant gratification, but it doesn’t involve the same craftsmanship that goes into wet plate collodion photography.

To see more of Guy's photography or to enquire about a portrait shoot, head over to his website.

Read more:

The best film scanners

Best vintage lenses

Best instant cameras

Having studied Journalism and Public Relations at the University of the West of England Hannah developed a love for photography through a module on photojournalism. She specializes in Portrait, Fashion and lifestyle photography but has more recently branched out in the world of stylized product photography. Hannah spent three years working at Wex Photo Video as a Senior Sales Assistant, using her experience and knowledge of cameras to help people buy the equipment that is right for them. With eight years experience working with studio lighting, Hannah has run many successful workshops teaching people how to use different lighting setups.