The Camera Never Lies… or does it? UK exhibition considers the power of documentary photography

First part of a series called ‘What is Truth’ focuses on the role of photography in shaping the narrative of global events

Showing some of the past century’s iconic documentary photographs, The Camera Never Lies is an exhibition running at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, England.

Open 20 October 20, it is one of the strands in a six-part series of programming that considers the question ‘What is Truth’?

Co-curated by the award-winning former photojournalist Harriet Logan, The Camera Never Lies explores the impact and influence that photography has had on shaping – and in some cases, distorting – the narrative of major global events.

Visitors to the exhibition, hosted in one of the best gallery spaces outside London, initially encounter a ‘main wall’ of 48 photographs that show key moments over the last 100 years.

Many of these are familiar to us, captured by Don McCullin, Dorothea Lange, Robert Capa, Kevin Carter, Steve McCurry, Susan Meiselas, Nick Ut, Bruce Davidson and many more.

From there, The Camera Never Lies continues: one area explores issues of authorship in modern documentary photography, and another reflects on how artificial intelligence algorithms interpret images.

We caught up with Harriet Logan just after the exhibition opened to find out more about it.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The exhibition's full title is The Camera Never Lies: Challenging images through The Incite Project. How does the Incite Project relate to the exhibition?

I covered quite a lot of conflict as a photographer, much of it for The Sunday Times Magazine. I was always influenced by the greats of photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka and Eugene Richards – any photojournalist is always going to look to the historical greats for inspiration.

I stopped being a photojournalist after having children as they didn’t want me to work in conflicts, so I went into advertising.

Despite not wanting to continue as a photographer, I’ve never stopped loving photography and I was lucky enough to be in a situation where I could start collecting.

I had no particular ambition, I just started buying prints of the iconic images that made me want to pick up a camera in the first place – the first one was ‘Migrant Mother’ by Dorothea Lange. It built up from there, then it was Capa’s Normandy beach landing, then Koudelka’s ‘The Horse and the Gypsy’, which I absolutely love.

I was calling a gallery and asking them to help source prints, and Tristan Lund [co-curator of The Camera Never Lies] happened to pick up the phone.

He knew nothing about photojournalism and I knew nothing about art photography but he loved helping to find the prints that I was asking for and, over a couple of years, we built up a relationship. Then he left the gallery to work with me on my collection.

And what he brought to it was breadth. While I was strictly looking for photojournalism based on conflict – whether environmental, political or social – Tristan brought in photographers who looked at similar subjects but were doing it from a background in art.

I didn’t want to become a collector who just compiled huge amounts of prints and stuck them in drawers. For me, it was really important that the prints were framed and hung, and we have a building which houses the collection – there are about a thousand prints now.

I didn’t really set out to make the collection as big as it is, but it has become its own animal and needs very little feeding from us!

The ‘main wall’ of photos is a great introduction to the rest of the exhibition, so please talk us through your highlights of it.

I can’t presume that anyone knows these photographs; just because I know them doesn’t mean that everyone should. I’m hopeful that if anyone knows one picture on that wall, it will be Steve McCurry’s ‘Afghan Girl’.

If you think about the Vietnam War, then it has to be the photo by Nick Ut, or Don McCullin’s ‘Shell-shocked US marine’ would be the next one. What else? Off the top of my head, Capa’s Normandy beach landing.

The other subject I wanted to include was Gaza, and we were in contact with Belal Khalid, a Palestinian photographer who was working there until very recently.

He had put a picture on his Instagram of a dead child’s hand, which I found really moving, but we ended up using a picture he took at the funeral of one of the journalists who had been killed – more journalists have been killed in Gaza now than in any other war.

Because the conflict is still going on, it’s impossible to walk away and decide which pictures of it you’ll remember, but what you would remember is the number of photographers and journalists who have lost their lives there already.

And there’s Lynsey Addario. She’s an extraordinary photographer and has won a Pulitzer Prize for her picture in the exhibition that shows Russia targeting Ukrainian civilians – the dead family on the Irpin Bridge.

One picture which strikes me as something that people should remember is the one by Nilufer Demir of Aylan Kurdi, the boy from Syria who was washed up on a beach in Turkey.

It’s such a powerful image and should really punch us in the face – this kind of thing ought not to be going on in a so-called civilised world.

It can’t have been easy choosing the iconic images. You must have had to leave so many out…

Yes, it’s difficult to do an edit like that, because when you actually look at it there’s nothing about HIV, for example.

Another aspect is that historically most photographs have been made by white men and there are probably fewer women on that wall than there should be.

But there are more women photographers now than there ever have been and they’ll play a greater role in documenting our world going forward.

Photography hasn’t been something that women have tended to go into, so if there’s a lack of women on that wall it’s not for lack of trying. But I’m not going to include photographers just because of their gender.

How do you think the collection of photos fits into the exhibition’s title?

I think you can take ‘the camera never lies’ as a question and as a statement of fact. The fact that you know the reality, that someone has made every single image that you see, and the images are not AI-generated, they have been made by a person who has opinions and whose history defines what they choose to put in or leave out of the frame. And I think that’s important to remember.

When they were shooting on film, a photographer would make the picture and send the film back. Much later, the photographer would see their images in print, by which time picture editors would have selected what got printed.

Think about Robert Capa’s ‘The Falling Soldier’, taken during the Spanish Civil War. He made that picture when he was 21 and probably didn’t see it for a long time after it was actually shot. By the time it was published and had become such an iconic image, he’d lost control of it. Then there’s also the whole aspect of who took the picture and what their background or politics was.

There are two prints of the Soviet flag flying over the Reichstag [by Yevgeny Khaldei, shown on the ground floor]: the one that was released initially shows a soldier with watches on both of his wrists.

The implication of this was that the soldiers were looting. So that print was pulled and a second print was released, where one of the watches had been dodged out and the sky burned in to make the picture much more dramatic.

So to think that photography is objective, or has ever been, is ludicrous. We have always been able to manipulate pictures somehow, even by what we choose to include in the frame.

The Kevin Carter picture [‘Famine in Sudan, vulture watching starving child’] is another classic example. It shows a boy lying on the ground in a state of starvation with a vulture in the background; Carter got so much criticism about this picture that he later killed himself.

The reality was that the picture was shot in a feeding centre: if he had moved his camera slightly to the right, you would have seen that the child wasn’t on its own and he was actually almost as safe as he could possibly be.

I very much doubt that Carter just walked away and left the child there with a vulture, but making that picture was important because it makes the viewer have to think.

When you’re a photographer and you’re confronted with these situations your job is to produce pictures which will mean something back home. If the photographer picked the child up and never took the picture, then that picture would never have existed.

I think it’s really important to remember what our roles are as photographers. I know that photographers do get involved in some situations, but they’re not there caring little about what’s going on.

They do what they can but often it’s very limited. We don’t carry food with us; we’re there to document what’s happening.

There are two other parts to the exhibition. What was the thinking behind these?

The relationship between them is like a mirror. The first section is about looking at the iconic images which in some ways have shaped our visual concept of history.

Then we wanted to look at photographers who used the medium of photography to explore the truths that they felt were important to talk about.

So we have Max Pinckers [and Sam Weerdmeester] focusing on the controversy around Capa’s falling soldier photo that was taken during the Spanish Civil War.

The questions that always get asked about this picture are, ‘Was it staged’ and ‘Was it shot on a front line?’ The negatives on each side of that particular frame had disappeared and the location of the photo was unknown until 2009 when Professor José Manuel Susperregui used the topography seen in the background to identify where Capa was standing.

Max and Sam went to the location in 2017 and used scanning technology to make a huge photomontage to show where the picture was taken. Does it mean that Capa wasn’t on the front line? And that doesn’t necessarily mean that there wasn’t a sniper who could have shot the soldier.

Who knows what happened? But the juxtaposition between a historic image which is surrounded by controversy and this very factual image is beautiful. It was a no-brainer for the Incite Project collection and just had to be involved in The Camera Never Lies exhibition.

Then we have Ziyah Gafic and his pictures of personal effects recovered from mass graves in the aftermath of the Balkans War, all shot on stainless steel to remove his presence as the photographer.

There’s also Matt Black, who’s working on a huge, long-term project making incredible images about poverty in America, and Anastasia Taylor-Lind.

Collaborating with the Ukrainian journalist Alisa Sopova, she has photographed families living close to the front line in Donbas, Ukraine. Her ‘5K from the Frontline’ project is a series of pictures of fragments of artillery shells found in the gardens of the people she photographed.

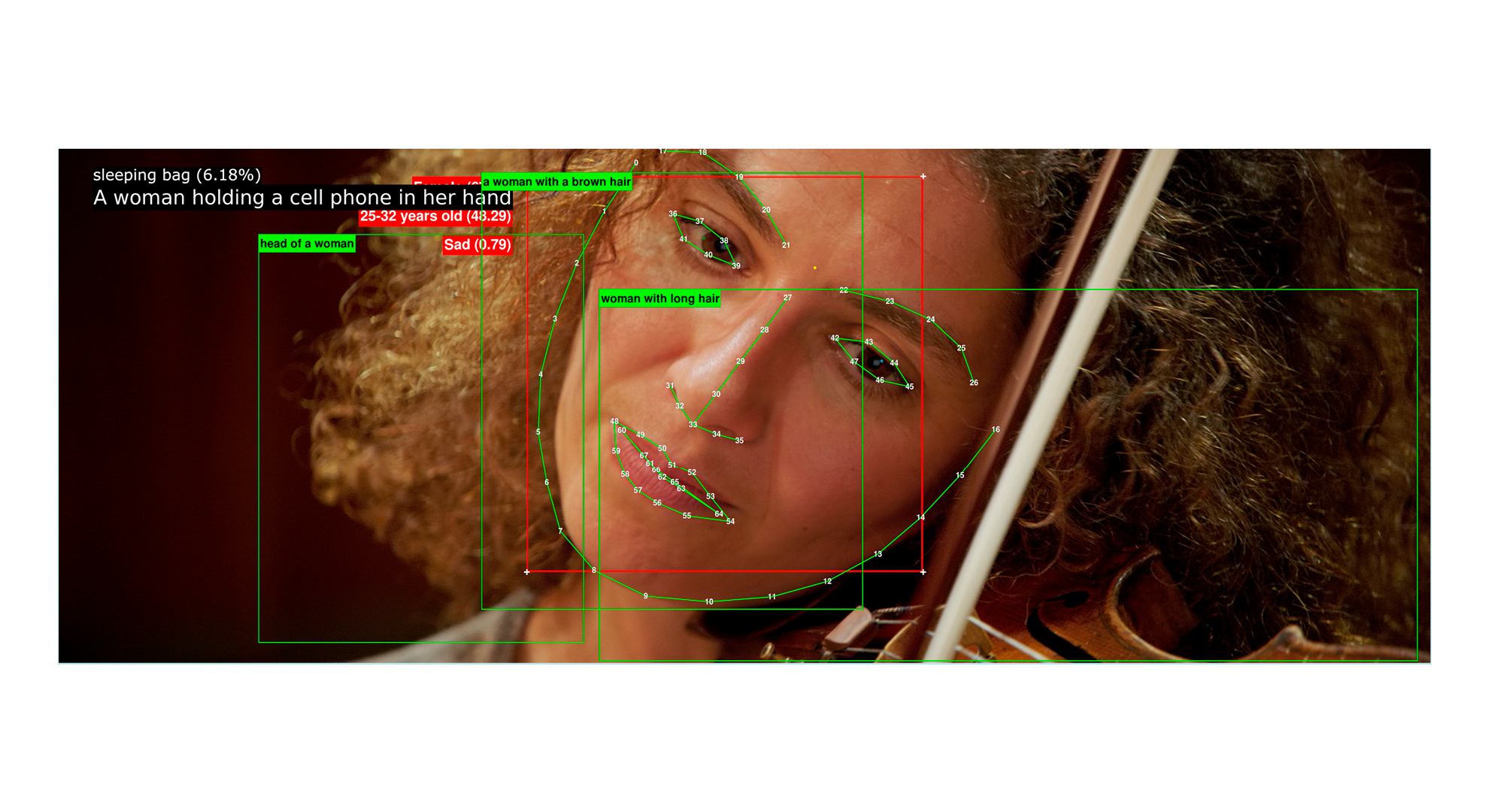

The third section of the show is ‘Image Operations Op 10’, an audio-visual installation by Trevor Paglen.

It’s a video of a string quartet overlaid by computer algorithms interpreting what the camera sees – ‘Woman with brown hair’, ‘Happy’, ‘Sad’, ‘Angry’.

It shows how AI works; it’s not saying that AI is good at making pictures, it’s just questioning the truth.

What effect do you hope the exhibition will have on visitors – to challenge their preconceptions?

Yes, and for them not to take everything at face value. I hope visitors will get a sense of the power of a single image, primarily from the main wall but also from the other areas.

On the lower level of the building, there are three photographs and a news video of the ‘Tank Man’ in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Four different photographers captured this moment, yet the Chinese authorities seem to have a collective amnesia about it.

For me, that’s the essence of The Camera Never Lies. A photographer’s role is to recall what happened, and that’s the main message of the exhibition.

It’s not about questioning truth within photography – some photos should definitely be taken with a pinch of salt – but we should also be happy that photography exists.

Visit The Camera Never Lies exhibition

The Camera Never Lies is open until Sunday October 20 at the Sainsbury Centre, Norfolk Road, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK.

Opening hours: Tues-Friday: 9.30am-6pm; Sat-Sun: 10am-5pm. Find out more at: www.sainsburycentre.ac.uk

The Sainsbury Centre houses the world-renowned art collection of Sir Robert and Lady Lisa Sainsbury so is a great day out – while you're there, check out works by Pablo Picasso, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and many other artists.

Harriet Logan worked as a photojournalist for a variety of publications including The Sunday Times Magazine. She covered many global conflicts in the 1990s and 2000s, including assignments in Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan. Turning to advertising after having children, Logan became a collector, acquiring many iconic prints of photojournalism. These have formed the basis of The Incite Project, a collection supporting photographers who seek social and political change.

The full version of this interview appears in issue 283 (July 2024) of Digital Camera World magazine. See the link below for our latest subscription deal.

All subscribers to Digital Camera magazine can now access digital back issues dating from 2009 (when using iOS) or 2012 (when using the Pocketmags Magazine Newsstand app or the Pocketmags website).

Digital Camera is the world’s favorite photography magazine and is packed with the latest news, reviews, tutorials, expert buying advice, tips and inspiring images. Plus, every issue comes with a selection of bonus gifts of interest to photographers of all abilities.

Niall is the editor of Digital Camera Magazine, and has been shooting on interchangeable lens cameras for over 20 years, and on various point-and-shoot models for years before that.

Working alongside professional photographers for many years as a jobbing journalist gave Niall the curiosity to also start working on the other side of the lens. These days his favored shooting subjects include wildlife, travel and street photography, and he also enjoys dabbling with studio still life.

On the site you will see him writing photographer profiles, asking questions for Q&As and interviews, reporting on the latest and most noteworthy photography competitions, and sharing his knowledge on website building.