The man behind the Olympus OM camera: Yoshihisa Maitani

The Olympus camera designer who put the M into the OM system

You know the brand name and you probably know some of the history behind it, but what about the people who made it happen? In this occasional series, we’re looking at the personalities who, through often courageous decisions, got us to where we are in photography today. In this profile, we meet the camera designer who was perhaps more influential than any other... and continues to this day.

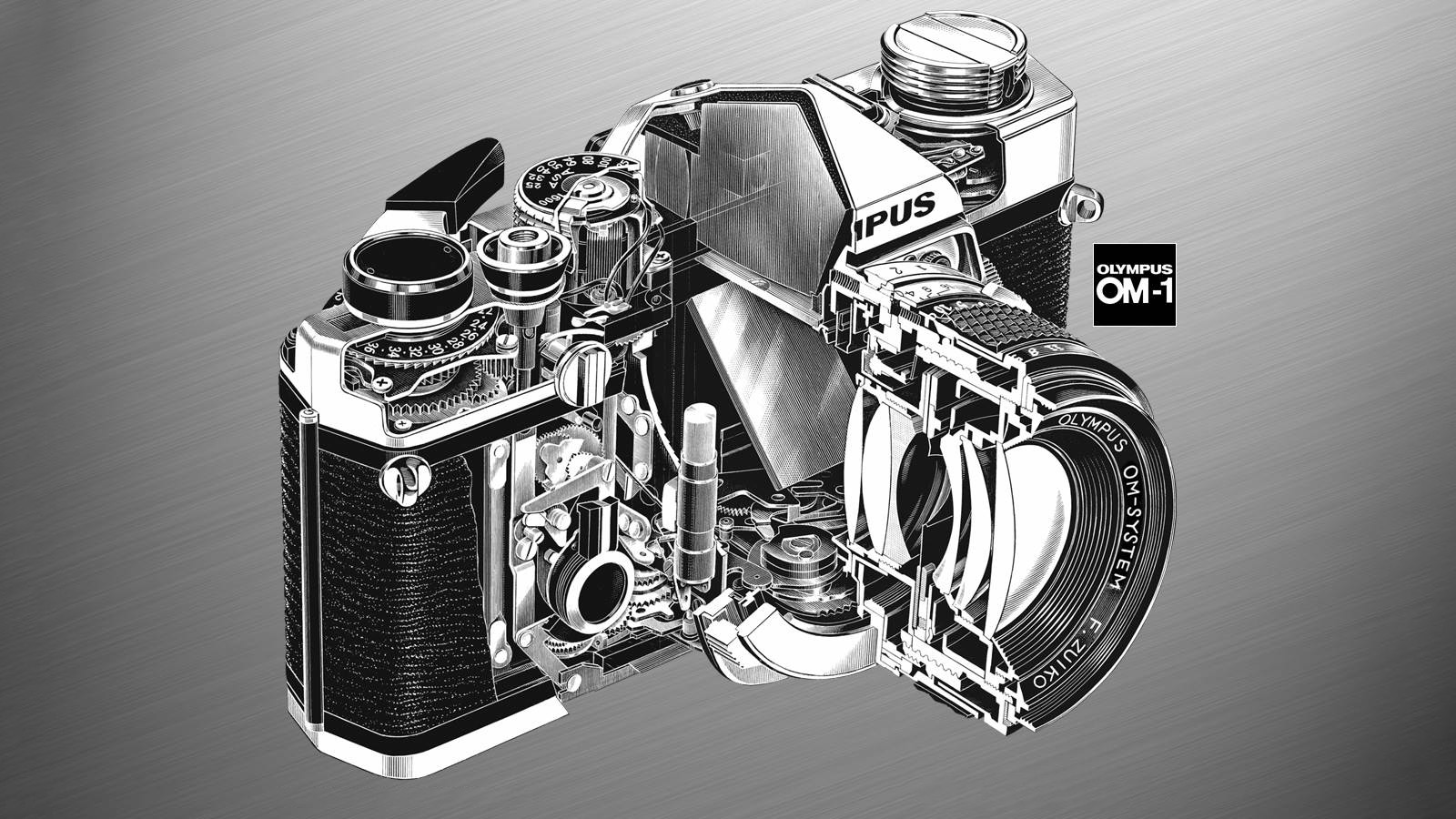

When the legendary Olympus OM-1 35mm SLR was unveiled at the 1972 Photokina in Germany, it had the model number M-1. The ‘M’ stood for Maitani, the talented designer who is best known downsizing the 35mm SLR, but who was also behind a string of hits for Olympus through the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. In fact, Maitani’s efforts helped turn Olympus into one of the ‘Big Five’ Japanese camera makers, alongside Canon, Minolta, Nikon and Pentax.

Yoshihisa Maitani was born on January 8, 1933, on the Japanese island of Shikoku where his family had a business making soy sauce. He described himself as “a wastrel son with a keen interest in photography”, and that keen interest was initially pursued with his father’s Leica IIIf.

“Though I loved photography,” Maitani recalled. “I had no intention of making it my career. It was difficult and demanding work, and I doubted whether I could make a living through photography, so I considered other careers. I saw photography as nothing more than a hobby that I could enjoy. There were no precision engineering courses at Waseda University, where I was studying, so I chose automotive engineering. I did basic research into engines, specifically what are now known as turbo engines. It should have been plain sailing, but I spent all my time taking photographs and wondering if I was on the right track. It was at that time that Eiichi Sakurai, creator of the first Olympus camera, happened to discover a camera patent that I had filed while still at school. ‘Come and work for us,’ he insisted. In those days a student who refused to work for the first company to offer him a job was regarded as a disgrace to his university. I had received a job offer from an automobile manufacturer, but I pretended that I hadn’t and so went to work for Olympus instead.”

Maitani’s many experiences with the Leica IIIf convinced him that it wasn’t an “all-round camera” and so he decided to design and build his own. Right from the start, he believed in making a camera as small as possible and, once he arrived at Olympus in 1956, he was also convinced that cameras had to be cheaper.

Still in training, he was given the task of turning his ideas into reality more as a design exercise than a commercially-viable project. Nevertheless, Maitani took it very seriously. A price tag of 6,000 yen was set as the target and, to make the camera as small as possible, he decided to base it on half a 35mm film frame which yielded an 18x24mm negative. Unlike the miniature formats, this would allow for a sub-compact design that still used the readily available 35mm film.

Impressed with the quality of Leica’s lenses, Maitani challenged Olympus’

optical design department to come up with something competitive in terms of sharpness... but on a half-frame camera. They did – the D.Zuiko 28mm f/3.5 – but not surprisingly, by itself it cost a lot more than 6,000 yen. Undeterred, Maitani pressed on with his design and, when the prototype was shown to Eiichi Sakurai, he immediately wanted to put it into production. Remarkably, the factory manager refused to comply, dismissing Maitani’s creation as a toy that had no hope of selling.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Even more remarkably, Olympus then allowed for production to be farmed out to a third party called Sanko Shoji. Launched in 1959, this camera was the first of the hugely successful Pen series and it was an instant bestseller... demand outstripping supply by a significant margin.

“When next we developed the Pen S, we priced it at 7,000 yen,” recalled Maitani. “The factory manager who had refused to produce the Pen now begged to be allowed to make this camera. I felt that I had at last earned recognition within the company, and that I had finally broken through the barrier of accepted wisdom. This was due in part to the support of my superiors, who were able to see beyond the barrier, but another factor was the support of the countless users who bought the camera after it was released.”

Boom and bust

The Olympus Pen cameras also made the 35mm half-frame format popular, particularly in Japan, and quite a number of other manufacturers subsequently launched cameras during the 1960s, including Canon, Fujifilm, Konica, Petri, Ricoh and Yashica. Maitani described it as “a half-size boom”.

He initially concentrated on designing ever-simpler Pen half-frame compacts, including the EE (1961) with built-in metering and automatic exposure control, but then he could see growing demand for a more advanced camera... and the idea ofa half-frame SLR with interchangeable lenses was born.

The main challenges here were to redesign the mirror box – as a 35mm half frame is portrait in its orientation – and then the focal plane shutter. Essentially, the mirror box was turned on its side so the reflex mirror flipped horizontally rather than down and up. However, this lengthened the mirror’s horizontal edges and it now snagged the shutter, so Maitani came up with a rotary design that worked a bit like a leaf shutter, but used a rotating disk made from titanium rather than blades. Nevertheless, a side benefit was that it still allowed flash sync at any shutter speed. Additionally, the Pen F – launched in 1963 – employed a porro-type prism design for its optical viewfinder (instead of a pentaprism) which allowed for a more compact and sleeker body. There were subsequently other 35mm half-frame SLRs, but all were based on full-frame models and so none could match the dedicated design of the Pen F (or the later FT and FV models) for smallness or lightness. Despite this and all the technological challenges that Maitani overcame, the Pen F series was, in his words, “a huge failure”.

“Because we took all the patents, no other company could manufacture this type of camera, and there was no boom.”

Raising Standards

Despite the commercial failure of the Pen F series, it provided the impetus to begin work on designing an ultra-compact full-frame 35mm SLR. Maitani decided

that the mainstream format was the way of the future.

The 35mm SLR was popularised with professionals in the 1960s largely through the efforts of Nikon and its groundbreaking F, while Pentax’s Spotmatic made it popular with amateurs. Olympus’ first full-frame SLR – the FTL introduced in 1971 – was

a competent but unremarkable camera that used the Praktica 42mm screwthread lens mount. Maitani realized this wasn’t going to cut the mustard in an increasingly competitive market.

“There is little value in producing a new camera that is hardly distinguishable from its competitors,” he wrote a few years later. “If, however, a new single lens reflex camera appears on the market that provides functionality and a system performance unavailable in previous cameras of this type, its welcome will be assured since it makes a true contribution to raising standards and establishing new values. If, in addition, it is the kind of camera that inspires increasing satisfaction as the photographer gets to know it better, it will gain a permanent place in his affections as an indispensable photographic tool. “To achieve such distinction was the aim of the OM System and the reason for its conception.”

His first challenge was to convince Olympus’ management that there was a market for a very compact 35mm SLR. He remembered, “It took the whole of 1967, from January to December, before they finally understood my concept”. This was

a major triumph because, previously, his superiors had thought it would probably be good enough to simply rebadge somebody else’s product.

“It had taken a year to break through the barrier of accepted wisdom,” he said. “We had finally reached a decision, albeit through coercion”.

Once he got the green light, Maitani set about achieving his goal of completely redesigning the 35mm SLR. He didn’t just want a slight reduction in the size or weight either, he wanted both to be halved, taking the Nikon F as the reference point. In the end, this proved to be over-ambitious, particularly because it would compromise durability, but nevertheless he still wanted something that would look and feel significantly smaller than anything else on the market.

The technical challenges were many, but Maitani noted that “the interior of an SLR is not all crowded; there are crowded areas and empty areas”. The crowded areas contained the core functions, such as advancing the film, releasing the shutter or changing the shutter speeds.

Maitani hit upon the idea of relocating some of these core functions to the less crowded partsmof the camera body and this, for example, led to the OM-1 having its shutter speed selector located around the lens mount. In the digital era, anything can really go anywhere inside a camera, but with a mechanical design, there were physical linkages – shafts, levers and gear cogs – to relocate, which was why rearranging the internal configuration of the 1960s-vintage 35mm SLR wasn’t as straightforward as it might seem today.

Nevertheless, Maitani was determined to make it work and later stated, “The concept of using under-utilized spaces was our first step on the road to developing a compact SLR”.

Millimetres matter

The first camera that his design team came up with didn’t actually look anything like the M-1 at all. It was called the MDN and it was essentially a scaled-down box-form camera – fully modular like Hasselblad’s 6x6cm format 500C with interchangeable film backs,viewfinders, lenses and a handgrip.

The year was 1969 and the MDN – the ‘D’ stood for “dark box” – was way ahead of its time as Rolleiflex didn’t come up with something very similar in the shape of the SL2000F until 1982.

The plan was to have two versions – MDN with the ‘N’ standing for “Normal”, and NDS with the ‘S’ standing for “Simple” – and the more conventionally styled M-1 was to be developed alongside as, essentially, the mass-market model, sharing the same lens mount and some accessories. In all cases, the ‘M’ stood for Maitani... well, “Nobody objected”, he later observed.

Maitani kept the MDN concept alive – evolving it into the OM-X – until it became clear just how popular the OM-1 was becoming and, in comparison, the modular camera would have been prohibitively expensive. Back in the late 1960s too, all the connections between the components had to be mechanical which, again, created various challenges that electrical contacts would have eliminated.

At the start of the 1970s work continued on the M-1 with the designer and his engineers trading in millimetres as they slowly transformed the dream into reality.

Maitani stubbornly resisted any requests to make the camera any bigger than he had decreed, but begrudgingly yielded when it was obvious it was really necessary, such as adding space for a seal to splashproof the battery compartment. Many years later, he still ruefully told audiences, “So the camera we have now is a millimetre taller than the dimensions that I first approved!”.

Apart from the reduced size and weight – the initial target was 600 grams for the body – Maitani was also demanding increased durability. For instance, he wanted the shutter assembly to be good for 100,000 cycles when, at the time, 10,000 actuations was considered acceptable.

He also wanted both the shutter and the reflex mirror mechanism to be quieter in their operations and create less shock. Alloys replaced brass for the body covers and the pentaprism viewfinder was completely redesigned to eliminate the traditional condenser (further saving weight). Even brass screws were replaced by steel ones which helped save a few milligrams. In the end, the OM-1 body undercut the target weight by a whopping 90 grams.

Just to add to his engineering team’s workload, development began on the OM-2’s electronically-controlled shutter and, along with it, a whole new way of metering. Instead of the metering cells being up in the viewfinder – which meant they stopped working when the mirror was raised – Maitani relocated them to the mirror box where they could continue taking measurements, firstly off the shutter curtains and then, truly revolutionary, off the film.

Pentax had devised the original ‘memory formula’ metering methodology which was accurate a lot of the time, but couldn’t take into account any sudden changes in the light that might happen after the reflex mirror was raised. Maitani’s system allowed for metering to continue right up until the exposure was completed, and it subsequently became known as TTL-OTF – through-the-lens, off-the-film.

Olympus initially called it TTL Direct Light Measuring and it was also a major breakthrough in terms of obtaining more accurate flash exposures via through-the-lens metering. The reflex mirror had a semi- translucent section in the center to facilitate metering when it was in the down position.

Small camera, big names

After the M-1 made its debut in September 1972, there was an immediate objection from Leica, who believed it had a mortgage on camera model numbers with the ‘M’ prefix... even though its M-series cameras were rangefinder designs and not reflexes. Production of the Olympus M-1 had already begun, but the ever-courteous Maitani agreed to a change and so, when his new baby was officially launched in May 1973, it was renamed the OM-1. Mind you, by that time an estimated 52,000 units badged M-1 had already been made and sold. The semi- automatic OM-2 followed in 1975.

The OM system put Olympus right up with Canon and Nikon in terms of its presence in the professional market. At the height of the 35mm OM system’s popularity, it boasted a veritable who’s who of big-name photographers – among them David Bailey, Patrick Litchfield, Uwe Ommer, Terence Donovan, Ernst Haas, Eric Hosking (best known for his stunning images of birds) and Don McCullin (who participated

in early testing of M-1 prototypes). It was the camera system of choice for National Geographic magazine’s photographers and there were plenty of celebrity users too, including F1 champion James Hunt, mountaineer Chris Bonnington, and British decathlete Daley Thompson.

After the OM-1 and OM-2, Maitani designed the XA series of ultra-small (for the time) 35mm compacts. The idea behind the XA was for a camera that could be taken anywhere and used at any time. Maitani and his team – by now he had a whole design department at his disposal – came up with a capless and caseless concept that used high-grade plastics throughout.

“There was intense interest in plastic at that time, but if you made a product from plastic it looked cheap. I am an engineer, but I also know a little about design, and I wanted to use plastic in a way that exploited the characteristics of the material without making the camera look cheap. So we used plastic for the cover that replaced the cap.”

The XA’s clever ‘clamshell’ design employed a sliding lens cover that also protected the viewfinder and served as the power switch. This made the camera truly pocketable and eliminated the need for an additional case. Launched in 1979, the XA was truly tiny at a time when microprocessors had yet to find their way into compact cameras, although this was partially achieved by omitting a flash (which was available as a clip-on accessory). Nevertheless, the XA still had an excellent 35mm f/2.8 lens and aperture-priority auto exposure control.

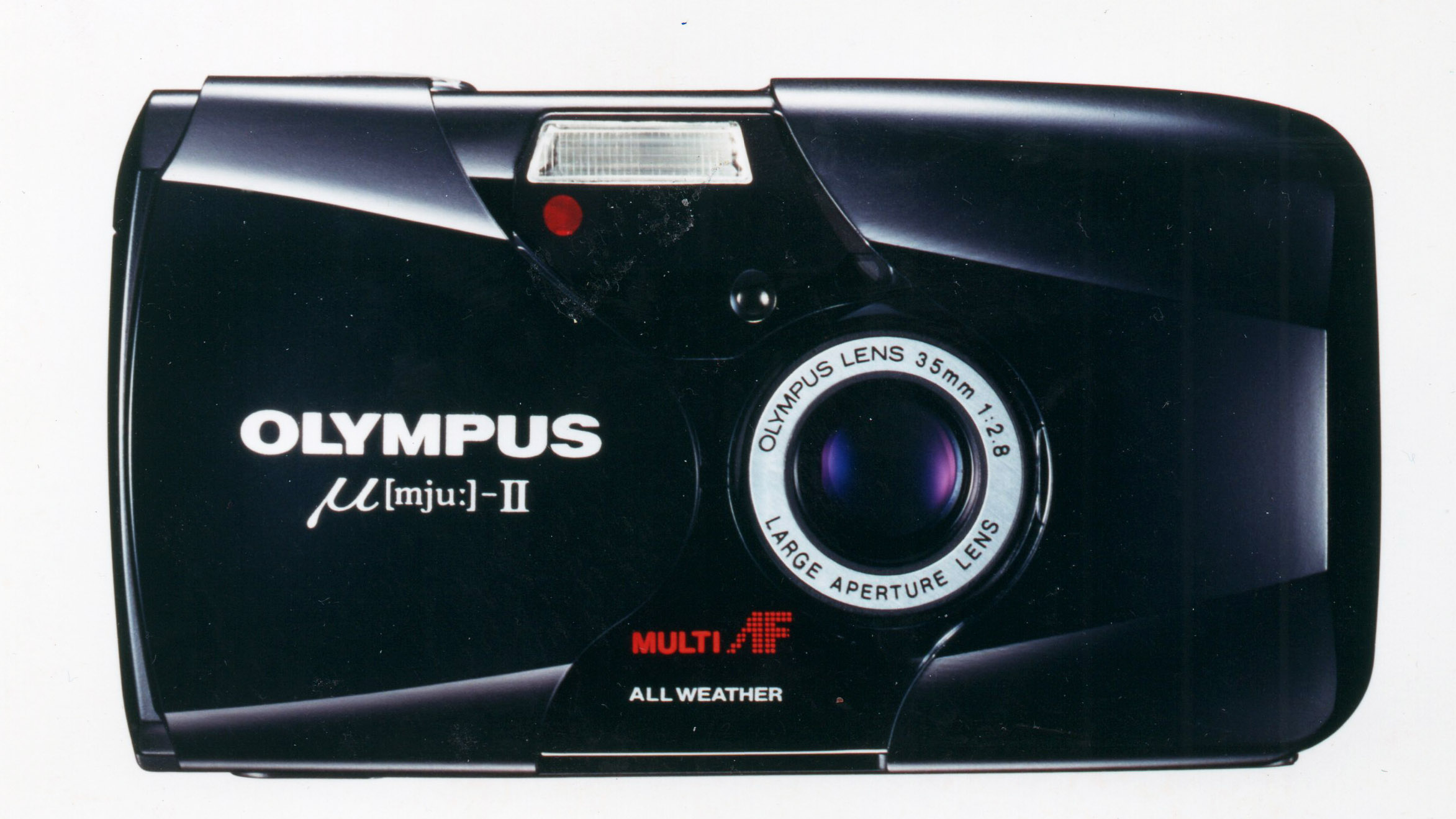

When Maitani did have micro-electronics at his disposal, he came up with another marvel of camera downsizing, the Olympus mju – or μ – which was launched in 1991. It again redefined how small a camera could be while still accommodating a 35mm film cassette, but now there was a requirement for a built-in flash, motorised film transport, autofocusing (which then used active IR triangulation to determine the subject distance) and a battery to power it all. The mju – badged the Stylus in the American markets – used a variation of the XA’s encapsulated design with a sliding cover protection all the important bits and also serving as the on/off switch. It was as slim as was possible with a 35mm film cassette, and was another huge hit for Olympus with the first model selling five million units on its own. The weather-proofed mju II, which followed in 1997, sold just under four million.

While there were only four variants of the XA, the mju family grew to over 20 models over three series and the name was then adopted for Olympus’ digital compacts.

Although Maitani was no longer involved in their design, Olympus continued to strive to make its digital compacts as small as possible and his influence was very much evident in the jewel-like mju-mini Digital which launched at the 2004 Photokina and featured a sleek aluminium body with an anodised finish in a variety of colors.

OM lives on

Later in life, Maitani reflected on the fortuitous intervention that diverted him from a career in automotive engineering to become arguably the most significant camera designer of the 20th century... with a company that was willing to listen to him even when he was still young and inexperienced.

“I love cameras, and I have wilfully proclaimed my determination to create cameras that have never existed before. Yet when I think about it now, it seems to be that everything was in the hand of Olympus. I’m sure that Olympus will continue to create unique cameras, and that those who love Olympus cameras will remain loyal users.

“Many of the cameras that I have developed have been unique Olympus-style products. And there’s a reason for that. I was simply trying to make things that you couldn’t buy anywhere.”

After 40 years with the company, Yoshihisa Maitani retired from Olympus in 1996 and he died on 30 July, 2009, aged 76. He left behind a rich legacy of camera design that has had widespread and long-term influences. Interestingly, while the Olympus name has gone from cameras, the OM designation lives on in OM Digital Solutions and the OM System branding. In many ways, Maitani is more present on today’s products than previously. It’s likely he would have approved.

At a lecture he gave in October 2005 at the JCII Museum in Tokyo, Maitani concluded, “My history is part of the history of Olympus. Since its early beginnings, Olympus has had a corporate culture characterized by the creation of innovative products. However, I have not inherited Olympus DNA; nor have I been taught about this culture. I never studied it. I simply love to take photographs, and if I needed something for that purpose, I would do my utmost to create it.”

Others in this series

The name behind Kodak: George Eastman

The name behind the camera: Victor Hasselblad

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.