The name behind Polaroid: Edwin Land

Meet the man who turned photography on its head with instant prints and devised a revolutionary film technology

Despite digital cameras delivering ‘instant’ images every time the shutter button is pressed, the instant print continues to appeal, creating a healthy business for Fujifilm with its Instax line, and plenty of investment in the revived Polaroid which, today, is re-creating a number of its original cameras as well as producing new products. There are plenty of other companies selling instant cameras – mostly based on Instax models – or refurbishing classics such as the Polaroid SX70.

This article originally appeared in Australian Camera magazine, one of Digital Camera World's sister titles Down Under. Click here to find out more about Australian Camera magazine, including how you can subscribe to the print issues or buy digital editions.

Is it the fascination with the idea of a unique one-off print? Or is it simply the whole experience of watching an image slowly form before your very eyes, as if by magic? Regardless, the instant camera was a hit from the very start and has remained so ever since, bouncing back from a lull caused by everybody focusing their attentions on digital imaging.

Of course, today’s market is essentially niche and concentrates largely on the fun factor, but at the height of the instant print’s popularity it was also seen as a very fashionable art medium – championed by the likes of Andy Warhol and David Hockney – and it was widely used by professional photographers for checking focus and exposure before committing a shot to film. Most medium format SLR camera systems included a Polaroid back for this purpose and holders were available for 4x5-inch and 8x10-inch large format cameras. Yes, there were 8x10-inch Polaroid instant print films (and it’s also since been revived).

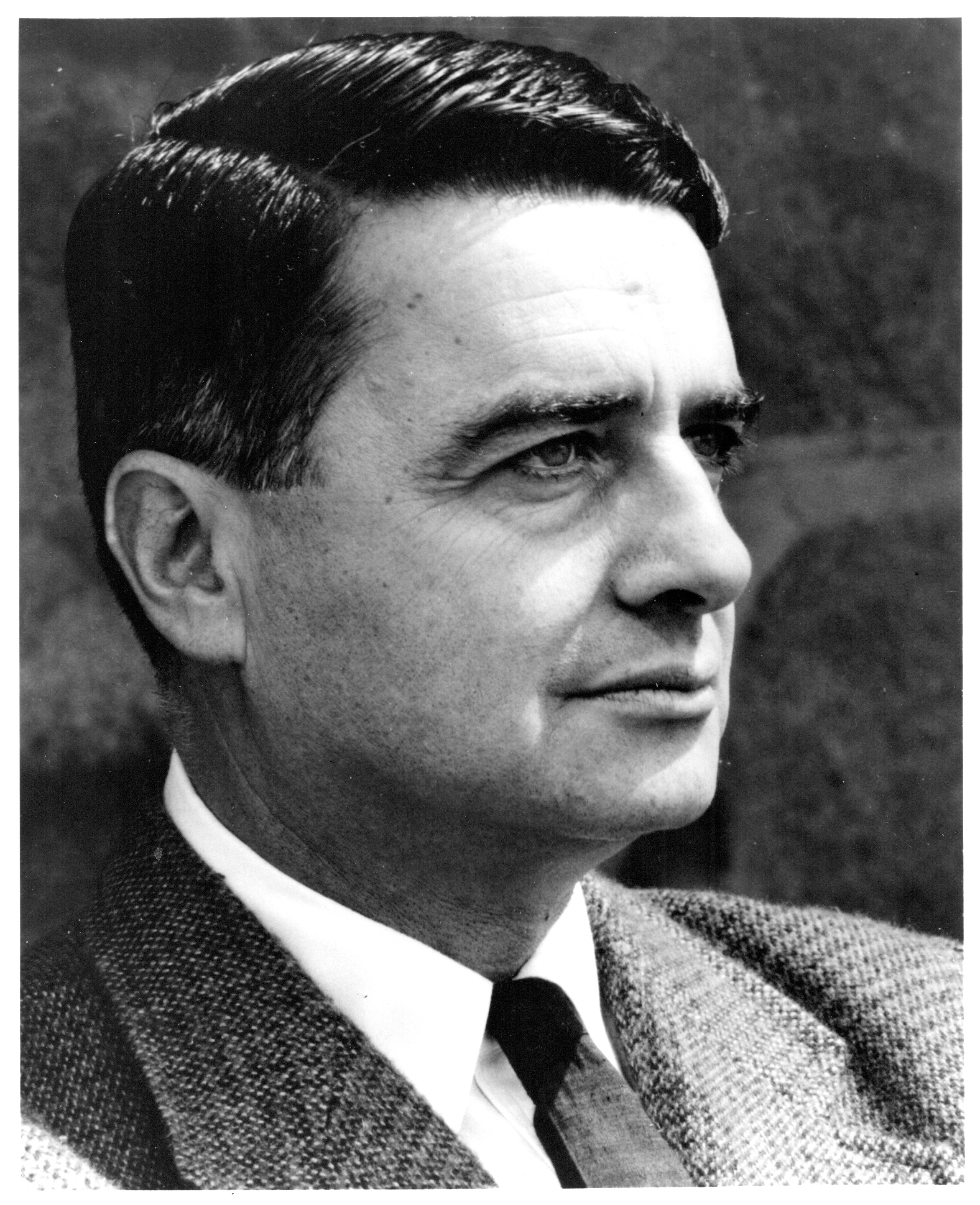

The genius behind the development of the instant photo print – also called the self-developing print – was Edwin Herbert Land, born on 7 May 1909 in the US state of Connecticut, the son of Russian Jewish refugees. From an early age, he was fascinated by the way things work and became something of a menace in his household, dismantling items like the family’s new gramophone player and regularly blowing the home’s electrics with his experiments. At Harvard University, Land studied physics, specialising in optics, but he left before finishing his degree, his eyes set on commercialising what he had learned about the nature of light polarisation and the materials that polarise light. In fact, the characteristics of light had been an obsession since he was in his early teens.

Lateral thinking

With street lighting still poor or entirely non-existent across most of America, dazzling headlights were the cause of many car accidents in the mid-1920s. Edwin Land set out to find a way of reducing that glare using the principles of light polarisation. He began experimenting with a material called herapathite, a crystalline substance made of iodine and quinine – discovered in the 19th century – which only passed light waves travelling in one plane and filtered out those travelling along any other. If two such crystals were superimposed perpendicularly to each other, all light was blocked from passing through.

However, the problem with herapathite was that it wasn’t possible to grow the crystals any longer than about three millimetres, which was too small to be of any use. Edwin Land’s solution illustrates his capacity for lateral thought. He worked out that a better approach was to use much smaller crystals – in fact, several billion of them per square centimetre – and then coat them in a thin layer onto a transparent sheet. He also found that the best way to obtain an even dispersion of the sub-microscopic crystals was to suspend them in a thick jelly-like substance that was then applied to the sheet... the same principle subsequently applied to his instant film processing reagent.

This breakthrough enabled Land to make the world’s first synthetic sheet polariser, a product with a myriad of applications including windows and, of course, sunglasses. The year was 1928 and Edwin was still only 19. His sheet polariser was patented on 26 April 1929. Keenly aware of the commercial potential of all his inventions, Land was careful to patent everything that could prove useful when he much later took on the might of Kodak over instant film infringements and won. Ironically, in 1934, one of Land’s very first customers for polarising filters was Eastman Kodak.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

While he failed to seal a deal with any American car maker for his polarised headlights (turning instead to making an accessory visor for the windscreen that reduced glare), he had far more success with applying the idea to sunglasses, both in selling the technology to others and making polarised sunglasses himself.

As his enterprise started to grow, Land realised he needed a brand name for his product and he turned to one of his key mentors – art history professor Clarence Kennedy – for assistance. It was Kennedy who came up with the “oid” component of Polaroid, derived from the polarising filter’s celluloid base material, but also representative of the suffix meaning ‘likeness’ or ‘similarity’. As it happens, Land wasn’t particularly happy with the name to start with, but stuck with it and, of course, it would eventually become one of the most recognisable brands in the world, ranking alongside Coca Cola and McDonald’s.

Multi-talented

Most articles about Edwin Land concentrate on his exceptional scientific prowess – especially his tackling of the many challenges of creating a self-developing print – but he was also a very fine photographer, another of his talents fostered by Clarence Kennedy (also a gifted photographer). He was also a musician – in possession of an excellent baritone voice – and a lover of both art and literature.

As Polaroid evolved into one of America’s leading technology corporations – pretty much the Apple of its day – Land became known for his erudite and thoughtful annual letters to shareholders, which always focused more on his grand visions than the minutiae of the accounts.

Not surprisingly then, Land was an eloquent spruiker of his company and his inventions, helped by the fact that he possessed piercing eyes that gave him considerable physical presence as well. Audiences paid attention.

During the late 1930s, Polaroid developed a range of products based on Land’s sheet polariser, including a 3D movie system first demonstrated in 1939 at the New York World’s Fair. In 1940, and with investors lining up for a slice of the action, Land adopted the Polaroid name for his rapidly growing company – Polaroid Corporation was born. After the USA became involved in the Second World War, Polaroid began supplying polarised goggles to the army, and its 3D system was used in aerial mapping to create prints – called Vectographs – that could be used with polarised glasses to give a realistic reproduction of terrain. Consequently, Polaroid had a good war, with the company expanding significantly thanks to its lucrative military contracts. But with the end of the conflict in sight, Land needed to find something else to keep his workforce – now numbering around 1,200 – in employment.

In 1929 Land married Helen Maislen – who was called Terre by her family and friends – and the couple had two daughters, Jennifer and Valerie. It was Jennifer Land who was instrumental in the next phase of Polaroid’s history. During the family’s Christmas vacation in Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1943, Edwin was taking pictures of his daughter, then aged three, with his Rolleiflex TLR. After the photo session, she asked the question, “Why can’t I see the picture now?”.

A solution-based solution

During the war years, Land had become known for his ability to quickly come up with solutions to any problems that might occur with his products, and he started thinking about his daughter’s question right then and there. Over the next few hours, he devised in his mind how a self-processing photographic positive might possibly work. He pretty much had all the theory in place by nightfall, but later confessed that it took the next 30 years to solve all of the practical problems, particularly in terms of creating instant colour prints. The rest of the night was spent writing notes and, remarkably, organising the details for a patent application.

Just three months later, Edwin Land exposed and developed a prototype instant photograph that was subsequently transferred onto a transparent plastic sheet. Incidentally, Land is often given the title ‘Dr’, but never formally achieved this qualification – in fact, he didn’t complete any university studies – although he subsequently received many honorary degrees during his lifetime, including from Harvard, Yale and Columbia.

To solve the considerable challenges of creating the self-developing photographic print, Land once again returned to the idea of suspending microscopic crystals in a fluid medium that could be then applied to a surface. The additional hurdle here was how to achieve that application in a device like a camera. What’s more, the application would have to be consistently and uniformly even. He would need two solutions, one chemical and one mechanical.

Land wasn’t particularly happy with the name Polaroid to start with, but stuck with it and, of course, it would eventually become one of the most recognizable brands in the world.

He also set a number of other goals for his system. For ease-of-use, it had to be dry and work in a wide variety of temperatures; the film had to be sufficiently sensitive for use without supplementary light; the images had to have the same resolution and sharpness as conventionally produced prints; the finished prints also had to be archivally stable; and, finally, the whole process had to be completed quickly enough to be a desirable alternative to conventional photography. No pressure then.

Land initially came up with the idea of a foil pouch that could be crushed by rollers in the camera to release the developer. He also worked on the consistency of the suspended developer, and the first trials of the concept used a simulated base made from mayonnaise and eggnog. From his earlier experience with the manufacture of a synthetic sheet polariser, Land knew that if a substance was applied to a surface in a highly viscous, jelly-like form rather than as a liquid, it was possible to obtain a very clean and even coating. The instant processing reagent was affectionately nicknamed ‘the goo’ by Polaroid, and was a highly complex brew of powerful chemicals, including a rapid-acting developing agent and a photographic fixer (or silver solvent).

The project was divided into three key elements – the negative, the developing chemicals, and the positive image receiver sheet. Initially, commercially available B&W negative film was used, but to create the image receiver, Land once again applied the principles derived from creating the polariser sheet. He devised a positive emulsion employing billions of microscopic crystals that formed catalytic areas called ‘galaxies’. Dissolved and unexposed silver grains from the negative are attracted to these microcrystal galaxies, which incorporate metal salts to cause a chemical reduction and produce a silver/black image. The incredibly small size of each image ‘building block’ resulted in excellent sharpness and resolution, a good tonal range and high efficiency for a given ISO.

The sealed pod concept allowed for ‘dry’ processing and it also eliminated any oxidation, enabling the use of more concentrated chemicals that could enhance the efficiency of the film and so attain the necessary ‘speed’.

Instant success

By the start of 1947, Land’s system was ready to be shown to the world. It was first demonstrated on 21 February in New York to a meeting of the Optical Society Of America, which was also attended by the press. He took a self-portrait with an 8x10-inch camera and the exposed negative was sandwiched with the receiver paper, ready for the reagent pod to be squeezed open as the sheets were run through motorised rollers. Demonstrating considerable faith in his product, Land told the spell-bound audience, “Fifty seconds” and set a timer. Once the countdown had elapsed, he peeled apart the two sheets to reveal the portrait he had taken mere minutes earlier. The moment was undoubtedly one of photography’s biggest ‘big bangs’.

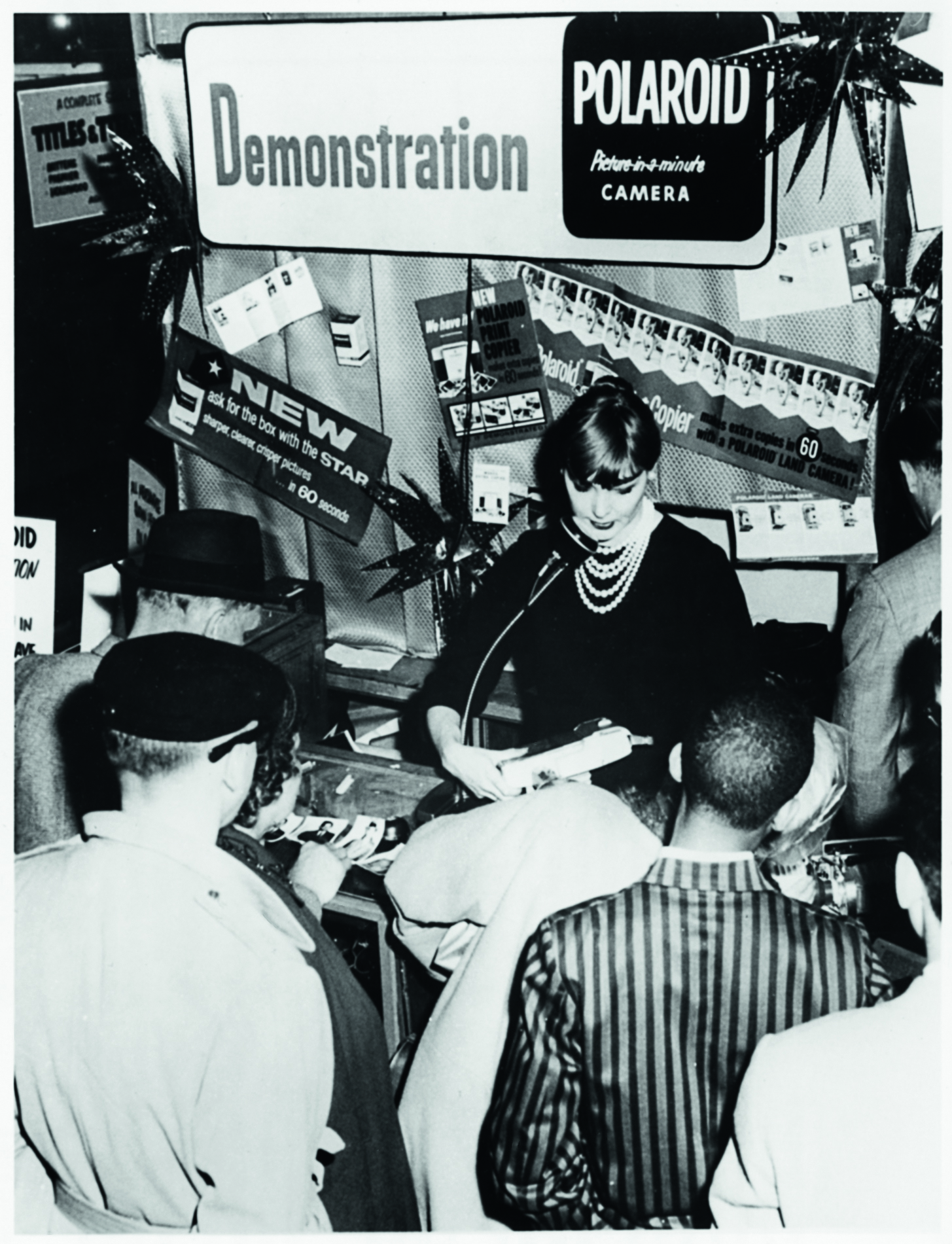

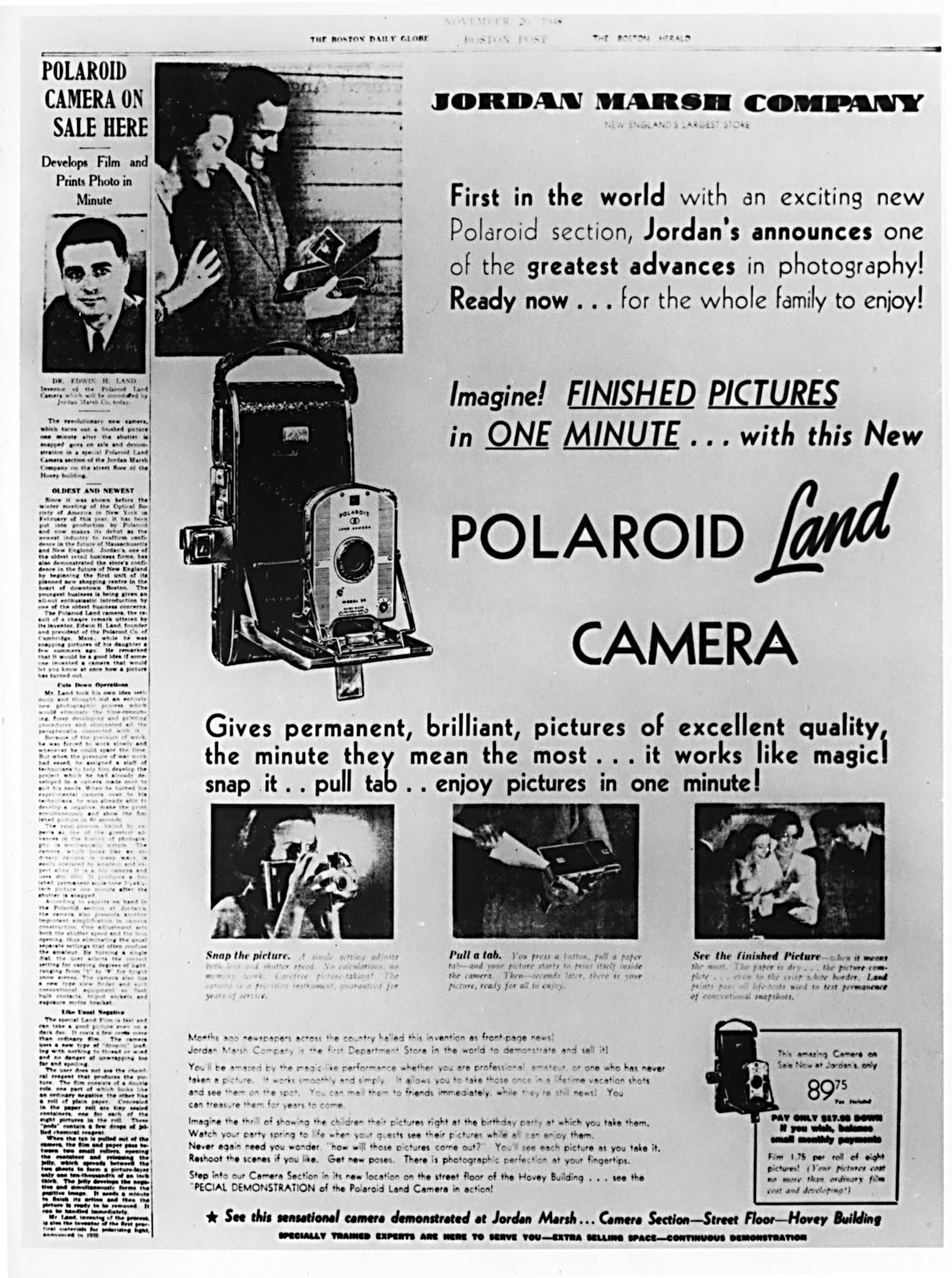

The branding ‘Land Camera’ was adopted for Polaroid’s cameras and the very first, called the Model 95, went on sale on 28 November 1948. At just under US$90, it cost as much as a good weekly wage, but this didn’t stop it selling like hot cakes. Many stores sold all their stock of cameras and film – designated Type 40 – on the first day.

While it worked, the first system was still quite involved and far from being a one-step process. A special negative film – ironically manufactured by Kodak – was married to rolls of die-cut receiving sheets, with a pod of processing reagent attached to the leading edge of each print. After an exposure was made, the positive-negative sandwich was pulled from the camera and passed through rollers that ruptured the pod and spread the ‘the goo’ between the two sheets. 60 seconds later they were peeled apart to reveal a B&W print with a brown tone, which then required coating with plasticiser to prevent fading (caused by residual developer).

Subsequent refinements gave neutral black-and-white tones with better contrast, coating-free films, processing times as fast as 10 seconds, ISO 3000 sensitivity (introduced in 1959 with Type 47 film), negative-plus-positive materials, and ‘self-contained’ peel-apart sheets.

Edwin Land’s next major goal was instant colour photography, an even greater challenge as it involved devising a one-step process to replace the (then) 22 steps involved in processing and printing a conventional colour negative film. Again, he set some pretty ambitious objectives, including a total process time of less than a minute, and the creation of a film that contained everything needed to deliver a dry, ready-to-handle colour print that didn’t need either washing or coating. A top-secret laboratory, designated the ‘SX-70’, was established to work on the ‘Polacolor’ project, headed by a gifted chemist called Howard Rogers.

Initially, Land and Rogers experimented with the silver diffusion transfer (SDT) process – as used in the B&W Polaroid system – and an additive colour screen comprising extremely thin red, green and blue filter lines. This idea didn’t work with SDT technology, as the screen blocked out too much light, but it was still patented (in 1946) and later formed the basis of the Polachrome instant slide system introduced in the 1980s.

Attention turned to the colour-coupler process, which is the basis of conventional colour film and involves the transfer of coloured dyes. Land and Rogers considered the idea of placing already-formed dyes in the film (a development of the old Autochrome process), but the key issue was making these dyes move in a controlled way from the negative to the receiving sheet.

Rogers came up with a method of linking each dye molecule to a molecule of developer that could be used to control the final image. This was called the dye developer process and the grains of silver in the negative have a direct one-to-one correspondence with molecules of dye; and whether or not those silver grains were exposed determines precisely whether or not the corresponding molecules of dye (solubilised by the developing agent) will transfer to the print receiver. In Polacolor negatives, the pre-formed dyes were transferred, upon exposure, to a receiving sheet in a carefully controlled manner to form a full colour image in about 60 seconds.

The next step to One-Step

The first Polacolor instant film was introduced in 1963 along with a dedicated camera, but the print still employed the twin-sheet neg-pos arrangement, which had to be peeled apart after development. Edwin Land knew he hadn’t reached his ultimate goal yet, and he continued to pursue the idea of a system that was completely effortless and truly one-step. His vision, he explained in 1970, was for a camera “..that would be like a telephone: something that you use all day long… something that was always with you”.

Land was also facing increasing pressure to deal with all the waste that the Polaroid peel-apart colour films created, and there continued to be on-going issues with inconsistent coating (and hence development) related to how fast or slow the material was pulled through the camera’s rollers. And the prints were very much at risk of damage until they’d dried.

Work had begun on the project named ‘SX-70’ in the mid-1960s and it took 12 years to get all the components right, along with a huge amount of investment, estimated to be possibly as much as US$1 billion for the camera and another billion for the film. Nevertheless, the SX-70 system – the project code was carried through to the final products – is arguably the most remarkable combination of optical, mechanical, electronic and chemical wizardry ever invented. Land demonstrated the SX-70 to Polaroid’s board of directors in April 1972, again rendering an audience spellbound by taking the camera from his jacket pocket, unfolding it and firing off a sequence of five prints in quick succession. When the system was launched in October 1972, Life magazine featured Land with the SX-70 on its cover under the headline “A Genius And His Magic Camera”.

Truly revolutionary in both design and operation, the Polaroid SX-70 was the world’s first folding reflex-type camera, the first camera to incorporate a fully automatic exposure system, and the first to have built-in electronic monitoring of its functions, which prevented operation if something was wrong. Additionally, it was the first instant camera to have automatic processing and print ejection rather than requiring manual extraction. Furthermore, SX-70 film was the first self-timing, daylight-developing, non-peel-apart instant photography material. It incorporated a multi-layered negative containing pre-formed imaging dyes, a sealed foiled pod containing the processing reagent, and the image-receiving layers. The really clever part was the opacifier, which was essentially a chemical dark slide that prevented any further exposure while the print was developing, but then magically became clear to reveal the image beneath.

Additionally, because the processing ‘goo’ remained a permanent part of the print, it included titanium dioxide pigment that provided a super-bright white background against which the final image was viewed. The highly alkaline reagent was neutralised by polymeric acid in the film’s receiver, and converted to water that evaporated to the outside of the print leaving a hard, dry, and stable image.

The SX-70 camera was equally ingenious, including a double-sided viewing/exposing mirror that was like a bright reflex viewfinder, but also allowed a folding design compact enough to fit into a handbag. To meet the camera’s considerable power requirements, a flat-form battery was incorporated into each film pack. Just 3mm thick and weighing 19g, this battery delivered a huge amount of power – the SX-70 motor required two amperes of current at six volts – for such a small package.

Clouded vision

With the Polaroid SX-70 system, Edwin Land achieved his long-term goal, which had always been to provide “absolute one-step photography”. But brilliant as it was, the SX-70 suffered some inevitable teething problems – including issues with the in-pack battery – and it took nearly two years before its sales started to justify the huge development costs.

However, Land would overreach with his Polavision instant movie film system that was launched in 1977, just as the video cassette was arriving on the market, backed by the growing might of Japan’s consumer electronics industry. Having been warned by Sony’s famed founder, Akio Morita (who was a friend), that Polavision was probably a decade too late, Land nevertheless soldiered on, but eventually had to accept his biggest failure to date.

By mid-1979, Polavision was dead, but Polaroid was still doing well with its instant print cameras, and had begun legal proceedings against Kodak for a range of patent infringements found in its EK system that launched in 1976. The case dragged on for over 14 years and the settlement of US$925 million, awarded in October 1990, remains the biggest ever (to be actually paid out) in a US patent infringement case.

But by now Edwin Land was long gone. He retired from Polaroid in early 1980, mainly as the result of run-ins with a more financially conservative management that was no longer willing to indulge in his expensive dreams and schemes. However, Polaroid without Land was essentially rudderless and devoid of new ideas, especially in the face of the looming revolution that was digital imaging. There were subsequently a couple of new and reasonably successful instant film camera systems – most notably Spectra and i-Zone – and some early experimentation with digital imaging, but the Polaroid that Edwin Land had created quickly fell behind and ultimately never recovered, filing for bankruptcy in October 2001.

After leaving Polaroid, the man himself continued with his experiments and founded a research institute that has subsequently become part of Harvard University. During the last few years of the 1980s, Land’s health was in slow decline and he died on 1 March 1991, aged 81. He didn’t live to see the dramatic impact of digital imaging technologies on the practice of photography, but he would have undoubtedly felt some satisfaction at the survival and revival, against seemingly overwhelming odds, of the Polaroid brand, a number of its more iconic products, and the on-going fascination with the vision he turned into a reality.

Read more:

Polaroid Go review

Polaroid Now review

Best instant cameras

Edwin Land also invented polarizers and ND filters

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.