23 things you should check when buying a new lens

If you're spending a hefty sum on a new lens, it pays to know what you're getting. Here are 23 things to check before you part with your cash

Buying a new lens? Between similarly sounding names, cryptic suffixes and vast differences in price, there's plenty of room for confusion – so here's a quick rundown of what to think about.

Not all of the following applies to all lenses, and the absence of any of these features from a particular optic doesn't mean it's not the right model to go for. Nevertheless, it's well worth quickly running through the points over the following few pages to make sure you don't get any unpleasant surprises with any new lens purchase.

1. Focus options

Most lenses offer both manual focus and autofocus options, but some cheaper ones may only be manual-focus only. There should be a switch at the side of the lens that lets you choose between both (although these can be labelled somewhat confusingly).

Most lenses from the major brands – Canon and Nikon, but also third-party manufacturers such as Sigma and Tamron – will be capable of autofocus. Particularly cheap and expensive lenses from third-party manufacturers are typically the ones more likely to be manual-focus only, so make sure to check this if one of these lenses appeals.

2. Compatibility with your current (and future) camera

Lenses are typically designed to be used with either full-frame cameras or those with smaller APS-C sensors. That doesn't necessarily mean you can't use lenses designed for one on the other, but you will have a different effective focal length of each combination.

To complicate matters further, the situation is not the same with every brand. Nikon's full-frame cameras, for example, usually also accept lenses designed for the smaller DX-format (APS-C) sensor, whereas Canon's full-frame models do not accept the equivalent optics in Canon's own range.

Here's a quick rundown of what lenses from each range allow:

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Canon

EF lenses - designed for full-frame bodies but also compatible with APS-C sensor bodies

EF-S lenses - only compatible with APS-C bodies

Nikon

FX lenses - designed for full-frame bodies but also compatible with APS-C sensor bodies

DX lenses - designed for APS-C bodies but also compatible with modern full-frame Nikon bodies at a lower resolution

Sigma

DG lenses - designed for full-frame bodies but also compatible with APS-C sensor bodies

DC lenses - designed for APS-C bodies but also compatible with some other modern full-frame bodies at a lower resolution

Tamron

Di lenses - designed for full-frame bodies but also compatible with APS-C sensor bodies

Di II lenses - designed for APS-C bodies but also compatible with some other modern full-frame bodies at a lower resolution

Pentax

FA lenses - designed for full-frame bodies but also compatible with APS-C sensor bodies

DA lenses - designed for APS-C bodies but can also be used on the full-frame Pentax K-1 body at a lower resolution

3. Maximum aperture

The maximum aperture of the lens determines the extent to which you can increase the size of the opening inside it (through which light passes). Wide apertures make photographing in poor lighting conditions easier, and they help you to isolate a subject from other elements in the scene, but these lenses can be expensive.

Maximum aperture is always mentioned within the name of the lens. The way to check this is to look at the figure after the f or f/ in the name of the lens, or the 1: on the lens itself. The Nikon lens above, for example, has a maximum aperture of f/1.4.

4. Constant or variable maximum aperture

Prime lenses – ie those that have one focal length – only have one maximum aperture, as they can only be used at the same focal length at all times.

Zoom lenses, meanwhile, travel back and forth between different focal lengths, and many have a different maximum aperture at the wide-angle end to the telephoto one. Typically, you won't be able to use as wide an aperture at longer focal lengths as you can at the wide-angle end, and this can make it more difficult to get a particular shot.

This is known as a 'variable' maximum aperture as it changes according to your focal length. The opposite to this is a 'constant' maximum aperture, as the maximum aperture you can access stays constant – and this is common with more expensive zoom lenses.

They way to check whether a zoom lens has variable or a constant maximum aperture is to see what's written directly after the focal length in the name of the lens. One figure after the focal length means constant, and two means variable. As an example, the Canon EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM has a constant maximum aperture, and the Canon EF 28-135mm f/3.5-5.6 IS USM has a variable one.

5. Image stabilisation

If the camera on which you'll be using your lens does not offer image stabilisation, you may want to consider this in your lens. Such lenses will typically have a small premium but it's such a valuable tool that it's worth getting if you can.

6. Weather resistance

If you plan on using a lens in harsher conditions, make sure to check that the lens is weather sealed. This means that it's designed with seals at any points of water and dust incursion to prevent these from getting inside. The front element will typically be treated with a coating designed to repel dust, water and dirt. Obviously, make sure your camera is weather-sealed too!

7. Lens version

It's common for manufacturers to update their most popular lenses with new versions over time, and these are usually indicated with a II or III after their title.

New versions may be titled very similarly to the previous ones, but they will typically offer revised optical constructions and better focusing motors. You may even find newer versions fitted with features like image stabilisation.

8. Size and weight

Some lenses might not feel that heavy when you first pick them up, but you may feel differently about them once you start carrying them around for a whole day.

Not sure if a lens is too heavy? Consider renting it from a reputable retailer or hire company for day to get a better idea of what it's like to use with your specific body.

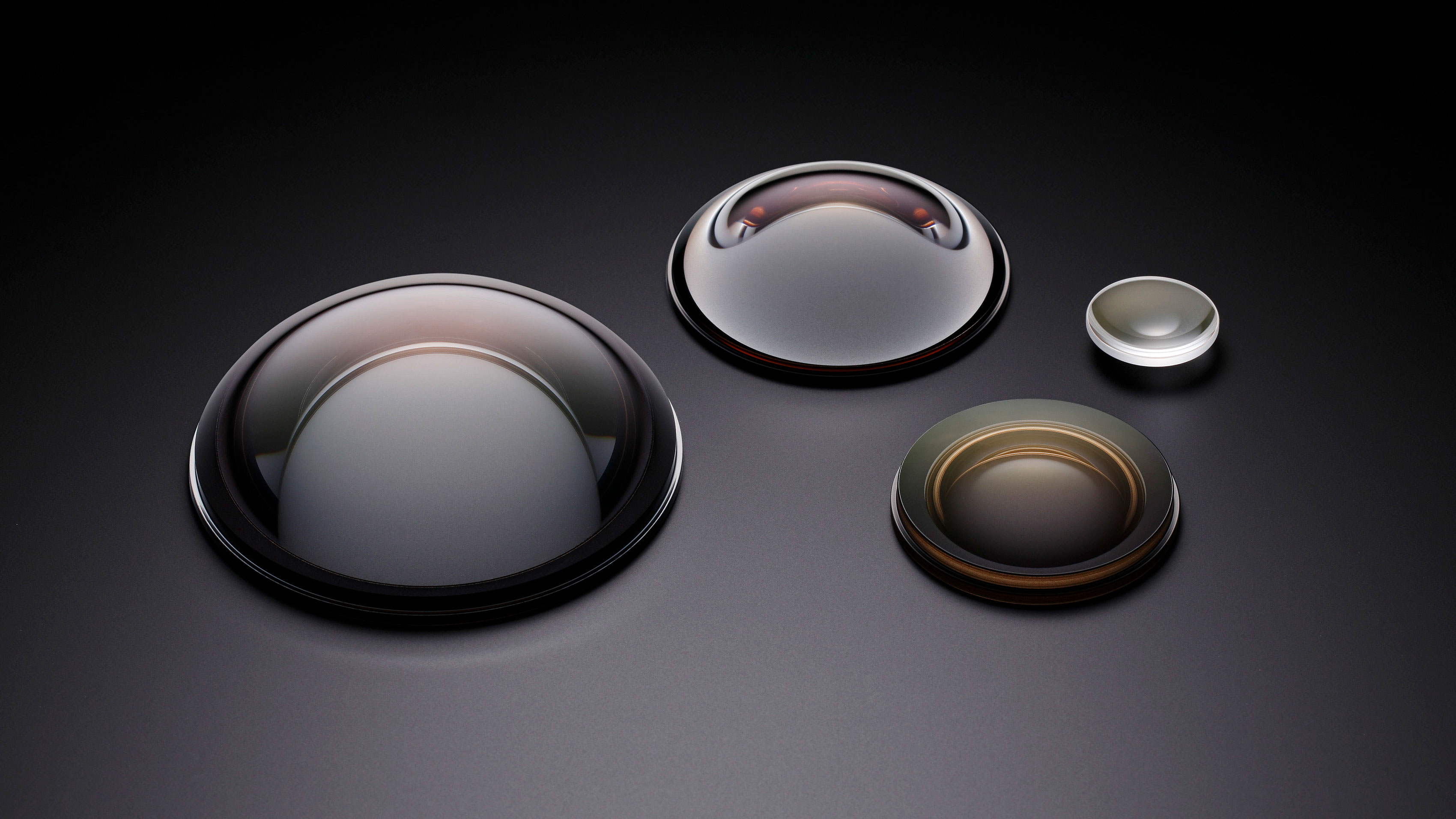

9. Lens coatings and special elements

Manufacturers tend to reserve special lens coatings to keep image quality high for their more advanced lenses. Canon, for example, uses Super Spectra coatings across a range of its lenses, but reserves its SubWavelength Structure Coating (SWC) for some of its pricier optics.

Similarly, Nikon user Super Integrated Coatings across all of its Nikkor lenses, but its Nano Crystal Coat technology, whose presence can be easily appreciated by the big 'N' badge on the lens, is only used in more professional lenses.

The absence of these doesn't mean a lens is no good, of course, but when you see these it confirms that this is a lens the manufacturer would intend for users needing the very best image quality.

Most lenses are designed with aspherical and low-dispersion elements to help keep aberrations out of images, but more advanced lenses may incorporate fluorite too.

This is known to be particularly effective in combating chromatic aberration, to the extent to a single fluorite element can take the place of a number of other elements, which helps to reduce size and weight.

Look out for Canon's red-ringed 'L' lenses, all of which make use of synthetic fluorite, as well as Nikon lenses that have FL in the title. Sigma also uses the term FLD, which refers to the use of elements that have the same optical properties as fluorite.

The former editor of Digital Camera World, "Matt G" has spent the bulk of his career working in or reporting on the photographic industry. For two and a half years he worked in the trade side of the business with Jessops and Wex, serving as content marketing manager for the latter.

Switching streams he also spent five years as a journalist, where he served as technical writer and technical editor for What Digital Camera before joining DCW, taking on assignments as a freelance writer and photographer in his own right. He currently works for SmartFrame, a specialist in image-streaming technology and protection.