When was photography invented?

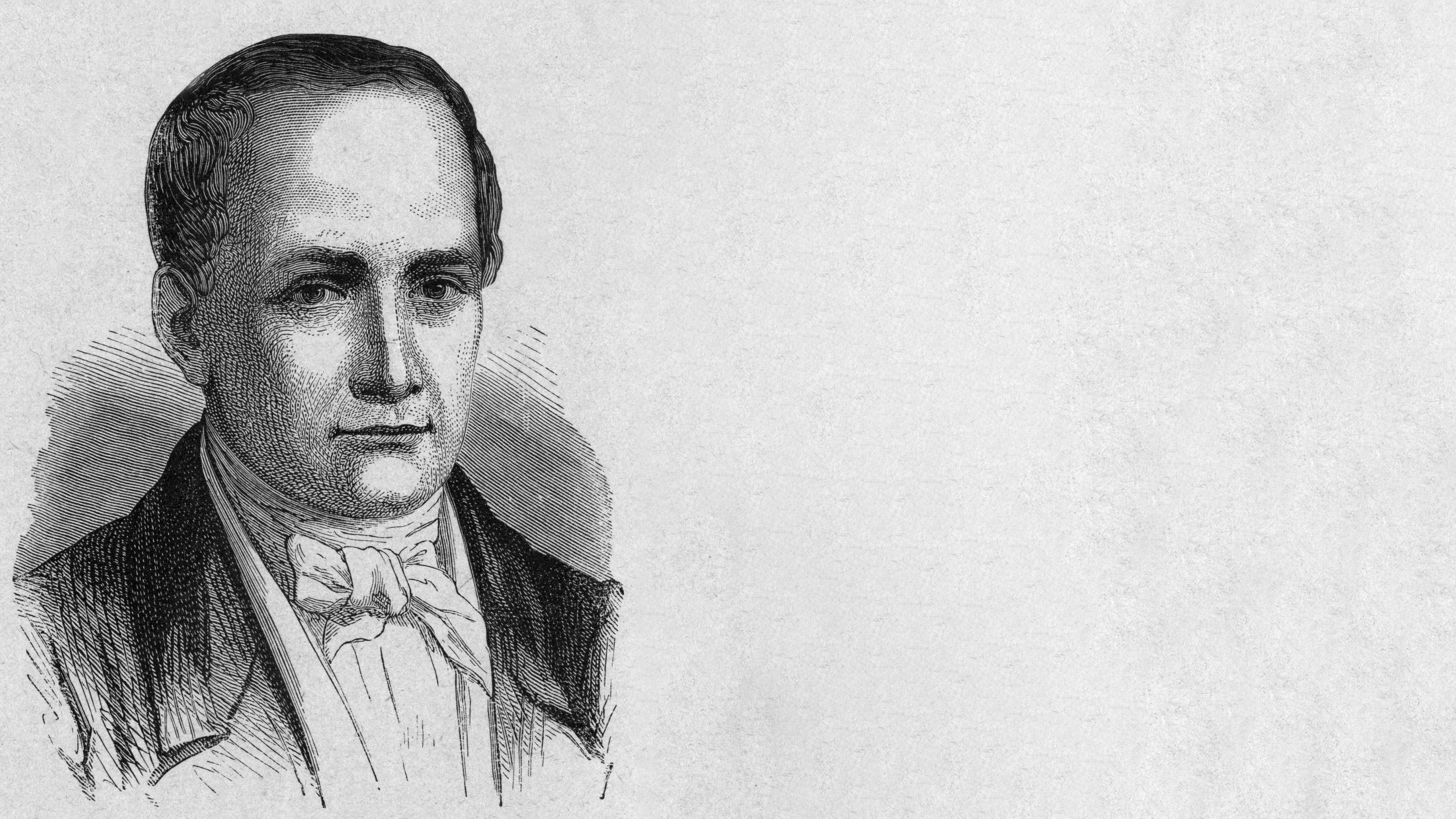

Frenchman Joseph Niepce is widely credited as the person who invented photography, nearly 200 years ago

When was photography invented? Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce is the person who takes the credit for taking the first permanent photograph in around 1826 – although he did not invent the camera.

After years of experimentation, Niépce succeeded in making permanent images from nature. He called his process ‘héliographie’, which translates as ‘drawing with the sun’.

The earliest surviving image (above) shows a courtyard at his house in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes in France. It was recorded onto a sheet of pewter plate, which was coated with bitumen of Judea, a light-sensitive compound.

An 8-hour exposure in bright sunshine resulted in a positive image, which was complete once the unexposed areas were dissolved in oil of lavender and white petroleum.

Niépce’s 1826 heliograph was dark and blurred and the plate had to be viewed from a certain angle for the details of the building to be visible. Nevertheless, it was undoubtedly a major breakthrough.

Niépce had previously made a copy of a 17th-century engraving using the same process. He also made another ‘heliograph’ in 1824 and described it in a letter to his brother: “I have succeeded in obtaining a picture as good as I could wish,” he wrote.

“The objects appear with astonishing sharpness and exactitude down to the smallest details and finest gradations. As the image is almost colorless, one can judge it only by holding it at an angle, and I can tell you the effect is downright magical.” This heliograph has not survived.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Niépce’s pioneering work was not recognized in his lifetime and he died in obscurity in 1833. It wasn’t until 1952 that the photo-historian Helmut Gernsheim discovered the image, stored in a London warehouse, and confirmed it as the world’s first photograph.

However, before his death, Niépce shared his process with his business partner, fellow Frenchman Louis-Jacques Daguerre, who went on to develop his own ground-breaking process – and is credited as the person who invented the camera.

The precursor to the camera

Niépce’s new invention used a camera obscura to create the image. This optical device could take the form of a light-tight box or a darkened room, with a small hole in one side that lets in light from outside. As light travels in straight lines, the resulting image of the exterior scene is projected, upside-down, onto the surface directly opposite.

The camera obscura had been in use for a long time. The term, first used in 1604 by the German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler, comes from the Latin for ‘chamber’ (‘camera’) and ‘dark’ (obscura).

The first known use of a camera obscura was in around 400 BC, by the Chinese philosopher Mozi. It was later by the Greek philosopher Aristotle. In the 13th century, Roger Bacon described using one to observe a solar eclipse.

Rudimentary lenses were added to the aperture from the 16th century onwards, to give a sharper and more detailed image. By the early 18th century, wooden camera obscura devices were being made that had a distinctly camera-like design.

Images made by a camera obscura were regarded as a visual wonder, a scientifically interesting phenomenon, and a useful drawing aid. However, beyond tracing their outlines by hand, it was impossible to make these images in any way permanent until Niépce’s invention.

Thomas Wedgwood

Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805) made the earliest documented experiments in recording images on paper and leather coated with light-sensitive silver nitrate - and therefore also has a claim to being the first photographer.

In a letter from the 1790s, inventor and mechanical engineer James Watt wrote that Wedgwood’s primary objective in these “silver pictures” had been “to capture real-world scenes with a camera obscura,” but those attempts failed.

The son of the famous potter Josiah Wedgwood, Thomas Wedgwood did succeed in capturing what Watt described as “silhouette images of objects in contact with the treated surface”, later called photograms. However, as Wedgwood lacked a means to make them permanent, the unexposed areas gradually darkened in daylight.

David Clark is a photography journalist and author, and was features writer on Amateur Photographer for nine years. He has met and interviewed many of the world's most iconic photographers and is the author of Photography in 100 Words: Exploring the Art of Photography with Fifty of its Greatest Masters.