Aerial photographer Edward Burtynsky gets first 2022 Sony World Photo Award

40 year career of Canadian photographer is rewarded with Outstanding Contribution Award

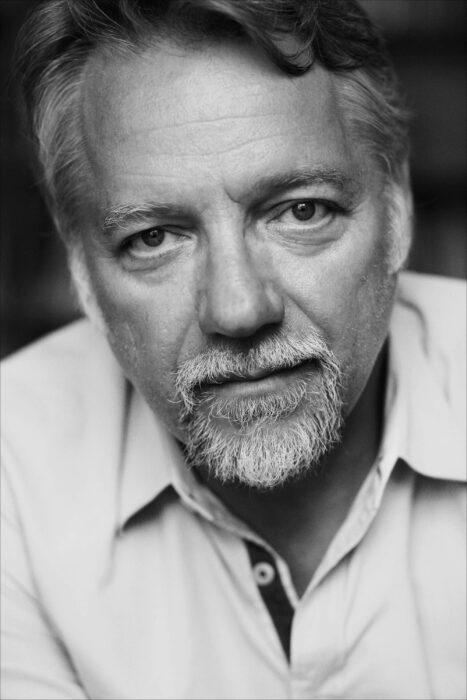

The World Photography Organisation has announced the first of the Sony World Photography Awards 2022. Renowned Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky is to be given the Outstanding Contribution to Photography award. Burtynsky is known for his large-scale aerial images of industrial landscape.

Over a dozen of his large-scale photographs will be displayed as part of the Sony World Photography Awards 2022 exhibition at Somerset House, London from 15 April - 2 May 2022. The selection, made by the artist, highlights key bodies of work and themes over his 40 year career. These include epic scenesfrom Anthropocene (2018).

To mark the award, we are running an interview from Professional Photography magazine that was published in 2018, to coincide with the launch of Anthropocene…

Interview with Edward Burtynsky in 2018

Edward Burtynsky photographs parts of the world we rarely see, but should know about. Among them are pristine rainforests being decimated, vast landscapes poisoned by industrial pollution, huge open-cast mines scarring the Earth and mountainous piles of waste. His message is clear: if we don’t change our behaviour the damage will be irreversible, with potentially dire consequences.

Burtynsky, 63, born and raised in Ontario, Canada, has been chronicling human impact on the Earth for the past 35 years. His images, often shot from an elevated or aerial viewpoint, sometimes seem like imaginative abstract paintings, yet each has an important story to tell.

His desire to show the scale of what we do to the natural world was inspired by his early experiences of Canada’s natural beauty. “I fell in love with photography as a young person by going

out and being in nature with a camera,” he says. “Canada has phenomenal areas of wilderness and I got to experience those natural riches. I got to sense what nature intended for the surface of the planet, versus how we re-engineer it.”

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

After graduating with a degree in photography and media studies in 1982, he began working in color with large-format cameras, photographing pristine landscapes. But he soon realised there was another way of approaching the landscape: showing the ways it has been re-shaped by human activity.

Burtynsky started by photographing open-caste mines, then in 1982 began a project on railcuts – studies of railway lines that sliced through the rocky landscapes of British Columbia. This body of work was a turning-point, attracted interest from dealers, collectors and museums, and effectively launched his career.

Getting established as a fine art documentary photographer is never easy and in the early 1980s Canada was in the grip of an economic recession. His early projects were largely funded through grants, but it wasn’t a reliable source of long-term funding. So, in 1983, Burtynsky decided to start his own company, Toronto Image Works, a high-end photographic laboratory. The income it generated funded his projects, while he company’s day-to-day work enabled him to gain valuable in-depth knowledge of processing and printing, which has enabled him to get the best out of his images.

The financial security the business offers has allowed Burtynsky to develop a formidable body of work. He’s since documented a broad range of subjects, including quarries, salt pans, shipbreaking in Bangladesh and industry in China, plus longer-term projects such as ‘Oil’ (2009) and ‘Water’ (2013).

Burtynsky’s approach involves first researching his subject, then exploring it photographically through the most spectacular examples he can find. If photographing quarries, he would go to “the mother of all quarries” and if exploring industrial pollution he would go to the most polluted places on the planet.

Some commentators have questioned his approach. “A lot of people say that I take these catastrophic, disastrous landscapes and aestheticise them,” he says. “I don’t see myself doing that. I see myself using the visual language to transmit back from those places in a way that makes us engaged. To me, it’s about understanding the scale of what we’re doing out there and using the medium to show landscapes that by and large are forgotten, and certainly places we would never go to ourselves.”

Today, although Burtynsky still runs his Toronto Image Works business, his projects are funded entirely by sales of prints to dealers, collectors and museums, as well as lectures and books. He has received major awards including the title of Officer of the Order of Canada (2006), Photo London’s Master of Photography (2018) and eight honorary doctoral degrees, and his work is held in the collections of 60 major museums worldwide.

His latest work, ‘Anthropocene’, is in many ways the culmination of what he’s been doing throughout his career. It’s an ambitious, multi-media project, to be released as a book, a feature length documentary film and two complementary museum exhibitions at the Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery of Canada. They’ve all been created in collaboration with cinematographer Nicholas de Pencier and director and producer Jennifer Baichwal. Flowers Gallery in London is also currently exhibiting new works from the ‘Anthropocene’ series.

The project is named after what an international body of scientists is proposing as the new geological epoch in which we now live; one that’s been entirely brought about by human impact on the Earth. It looks at mining, deforestation, farming and urbanisation and the way it shapes the Earth and the species with which we share it.

As Burtynsky notes in his book’s introduction, even during his own lifetime the human population has doubled, to 7.2 billion, and we now take almost 60 billion tons of material from the planet every year. “It’s clear,” he says, “that the expanding industrial metabolism is a major driver of global environmental change.”

The project has taken four and a half years to complete and has involved Burtynsky and the filmmakers travelling to every continent in the world except Antarctica. They have visited 20 countries and photographed and filmed at 46 different locations, many of them extremely difficult to access.

One example is the remote city of Norilsk in Siberia, above the Arctic Circle and one of the most polluted cities in the world. It’s a closed city to foreigners; even Russians need special permission to visit. It took 18 months to arrange to photograph there.

“When we got there, we were detained and got fingerprinted and they accused us of lying on our visa application,” Burtynsky recalls. “Another time, when we working in the Siberian town of Berezniki, I think we were detained five times in two weeks.”

He also photographed the Bagger 291 and 293, two of the world’s largest terrestrial machines by weight, at an open-pit coal mine in Germany. “We were standing at the foot of a machine that was 300ft high and 1,000ft long,” he says. “When it moved, the earth shook. It was like something from another planet.”

‘Anthropocene’ involved Burtynsky documenting both new and familiar subjects in new ways using technological advances. He tackled underwater photography for the first time, where he shot multiple images of the pristine coral reefs off the Indonesian island of Komodo and stitched them together to form huge, detailed prints up to 24ft wide. He also returned to document subjects he had covered earlier in his career.

“I first photographed quarries in 1993, but I hadn’t been back there until I returned a couple of years ago,” he continues. “This time I went with a whole new set of tools. We were doing virtual reality filming and shooting stills with a drone. It was also the first time I had used a 100-megapixel Hasselblad, which was almost like having a 5x7 camera up there.

“I was able to lock the drone in position, compose through a video screen and get crisp, sharp images back on the ground. Back in 1993, it was just me and my fixer. This time I went back with a crew of eight. It gave me an understanding of how, in the intervening 25 years, my world had changed.”

On the shoot itself, being in charge of a group of people means Burtynsky has to do a lot more than just take pictures, but concentrating on the images is crucial. “Within all that turbulence I had to keep focused on the subject and to not let all that stuff blow me off course,” he says. “I had to be a mental lone wolf; I had to figure out, ‘What is the picture here?’ Doing that was a discipline I got from working independently for my early work. It meant I could still drown out all that noise.”

Does he have any optimism that we can avert ecological disaster? “It’s hard to be encouraged these days because it seems that we’re not moving in any way fast enough for the problem,” Burtynsky says. “We’re up against a handful of powerful individuals running corporations who have a different idea of how they want the world to unfold and they have the resources to really shape that direction. I’m pretty disappointed with what the baby boomers have done. It seemed that getting rich was the main objective, and to hell with the world.

“However, many corporations and many politicians at a local level are encouraging the adoption of greener policies. I think the next generation coming up knows the deal and hopefully they’ll get power soon and do the right thing with that power. We need a proactive strategy. It’s technology that’s got us into trouble and I think it’s going to take technology to get us out of trouble.”

Read more

Best camera drones in 2021

Best medium format cameras

Best Sony cameras

Chris George has worked on Digital Camera World since its launch in 2017. He has been writing about photography, mobile phones, video making and technology for over 30 years – and has edited numerous magazines including PhotoPlus, N-Photo, Digital Camera, Video Camera, and Professional Photography.

His first serious camera was the iconic Olympus OM10, with which he won the title of Young Photographer of the Year - long before the advent of autofocus and memory cards. Today he uses a Sony A7 IV, alongside his old Nikon D800 and his iPhone 15 Pro Max.

He is the author of a number of books including The Book of Digital Photography, which has been translated into a dozen different languages.

In addition to his expertise in photography and videomaking, he has written about technology for countless publications and websites including The Sunday Times Magazine, The Daily Telegraph, What Cellphone, T3 and Techradar.