American identity explored in new photo book, 'The Good Citizen'

What is American identity? Photographer chats his new book, comprising 8 years of travel, 43 states and meeting 500 people

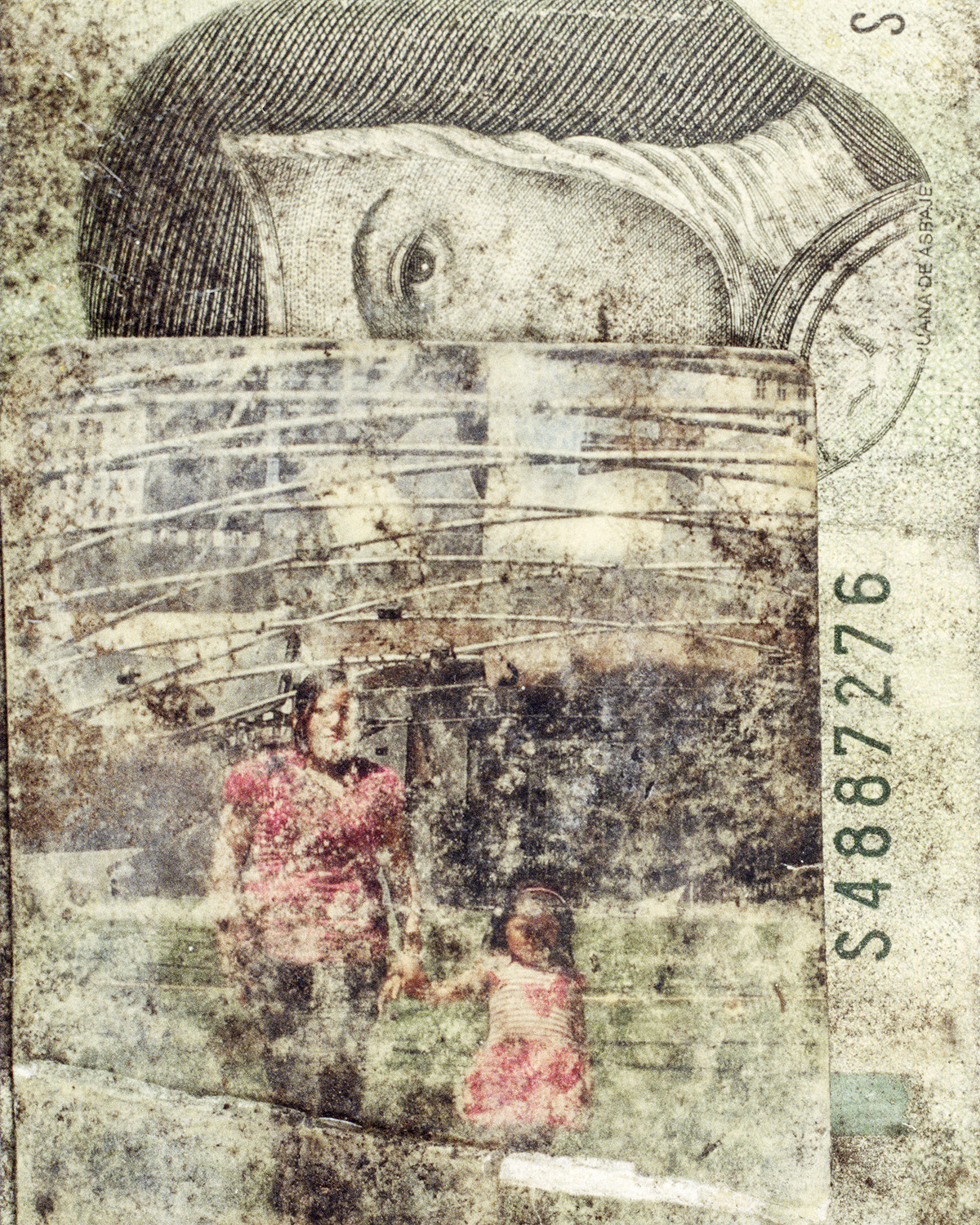

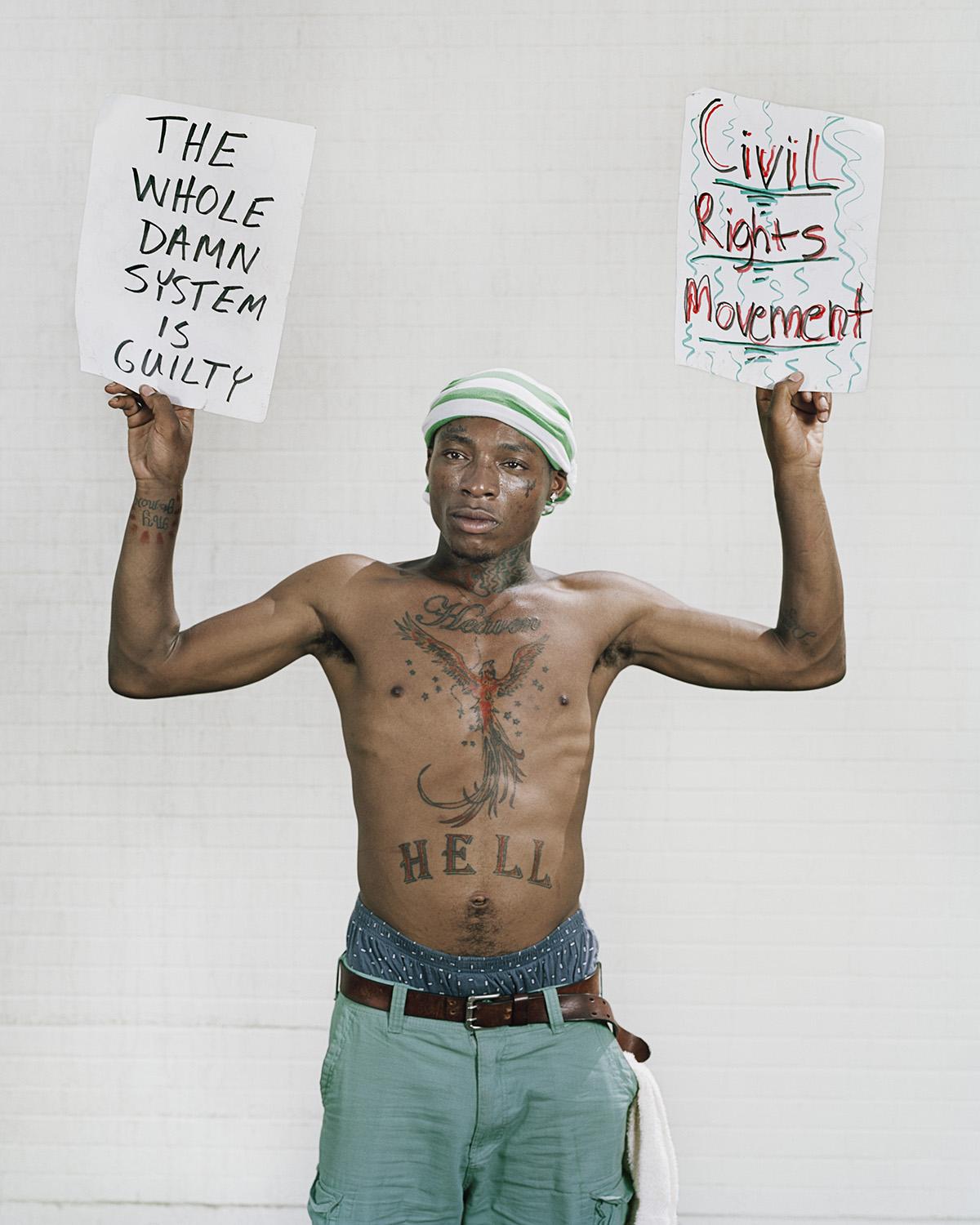

The Good Citizen is the debut book by Faroese-American photographer, Benjamin Rasmussen. As a self-confessed "outsider," Rasmussen wanted to explore how American society came to be what it is today and the complexities that make up the American identity. For the last 8 years, he has traveled through 43 different states and met with over 500 people to create his first photo book.

During his documentation of this diverse nation, Rasmussen has photographed everything from beauty queens and activists to abandoned everyday items and even a President. In a project first, Rasmussen shot using large format film and a Polaroid instant film camera so that his subjects could instantly have input about how they were being represented.

Accompanying Rasmussen's photos are a series of essays by legal scholar, Frank H Wu, who reached out after reading about the project in a magazine. Together with the photos, the pair hope to provoke conversation surrounding the complicated nature of American identity.

In the lead-up to the book's release in February, we caught up with Rasmussen to find out why American identity is such a point of interest, how the collaboration with Wu came about, and how the rising costs of film have impacted this project.

Interview: Benjamin Rasmussen

How did you come to collaborate with Frank H Wu, who wrote the essays included?

Frank saw a section of the project in a photography magazine. It dealt with beauty queens from immigrant communities that had been impacted by US naturalization laws, which limited citizenship to “free white people”. He wrote me and shared some of his research and writing, and we corresponded for the better part of three years.

Did you intend to set out and shoot The Good Citizen or is it something that came together over time?

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

I set out to examine the complexities of American citizenship and how the courts had created a structure that benefited certain people – namely white men such as myself – and disadvantaged others. But the complex structure of the project came together over time as I did historical research, and then tried to find the ripples of that history in contemporary society.

Over the last eight years, you must have met some interesting characters. Were any particularly memorable?

In 1946, two black couples were lynched on Moore’s Ford Bridge outside of Atlanta, Georgia. No one was ever prosecuted. In the late 1990s, people in the community created the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee. The director, Cassandra Green, leads a team of locals, both white and black, in a reenactment of the killings every year to bring pressure on law enforcement to re-open the case.

It is a call for justice, but also a raw revisiting of the worst trauma enacted on the community. To see someone shepherd a group through that type of experience was deeply inspiring and she is a model for how a community can grow and change.

Have you always shot on Polaroid and large format cameras?

I have shot on large format since the start of my career, but using Polaroid started with this project. I wanted a way of showing people how they were being represented and try and give them as much agency in that as possible.

What have you learned about American identity and has anything surprised you?

I learned how much American identity is deeply intertwined with white identity. And, like other identities, it is built up through a series of stories. Historian Richard Slotkin described this as a process that simplifies “centuries of experience into a constellation of compelling metaphors.”

When I first started I thought that I could just challenge some of those stories, but quickly found that this was threatening to viewers. So instead, I coopted those metaphors. I used stories of veterans, beauty queens, family lineage and more to talk about challenging topics in a way that felt familiar.

Has this project helped you to understand your place in American society, coming from a Faroese-American background and growing up in the Philippines?

Existing between such different cultures, I have always felt like an outsider. I needed to be able to work through what it meant to be American, and why it was an identity that was given freely to me and withheld from others. There are no neat and clean answers, but this project was part of an intentional effort to understand what my voice is within American society, with all of its complications.

Have you created a photo book before?

I have created a few zines over the years, usually newsprint and unbound. I love how photographs operate in a printed form, but I had never done a complete enough project to feel like it should be permanently put between two covers. Each of those projects were measured in months, but this one has taken nearly a decade.

Are you working on any new projects or will you continue this one?

The Good Citizen is finished, which is exciting because it gives me space to work on other things. I have one project looking at the impact of American Cold War policy in one community in North Africa in the works, and another about the legacy of one American administrator during the period when the Philippines was an American colony that is still in the research phase.

Which photographers do you admire and if you could work with anyone, who would it be?

I am currently really drawn to photographers who are looking at complex topics in new and interesting ways. Max Pinckers, Laia Abril, Rafal Milach, Sabiha Çimen, and Trevor Paglen.

The Good Citizen will be available to buy from February 2023 as a 240-page, hardback book with over 130 images by Rasmussen. You can pre-order directly from Gost Books.

Check out the best film cameras - recapture the magic of analog photography with our favorite 35mm cameras

Having studied Journalism and Public Relations at the University of the West of England Hannah developed a love for photography through a module on photojournalism. She specializes in Portrait, Fashion and lifestyle photography but has more recently branched out in the world of stylized product photography. Hannah spent three years working at Wex Photo Video as a Senior Sales Assistant, using her experience and knowledge of cameras to help people buy the equipment that is right for them. With eight years experience working with studio lighting, Hannah has run many successful workshops teaching people how to use different lighting setups.