Interview: Stuart Dunn on his love of travel, photography and humanity

Meet the photographer who has developed his passions into an award-winning, globe-trotting career

Multi-award-winning photographer and filmmaker Stuart Dunn was born in 1977 in Newcastle. He studied at the Northern Media School, where he gained a Masters in Screen Arts, and during his time there he embarked on his first filming expedition with fellow student, Pandula Godawatta.

On a shoestring budget, they travelled to the Tamil Tiger-controlled regions of Sri Lanka in an attempt to tell the story of the civil war that had raged for over 20 years.

• Read more: Best travel cameras

Since then Stuart has won multiple accolades for both his photography and film work. His assignments have taken him across the globe, photographing a wide range of topics from critically endangered animals to remote tribes.

He regularly works for the BBC Natural History Unit, National Geographic and Discovery Channel, filming internationally acclaimed documentaries that are screened to audiences around the world.

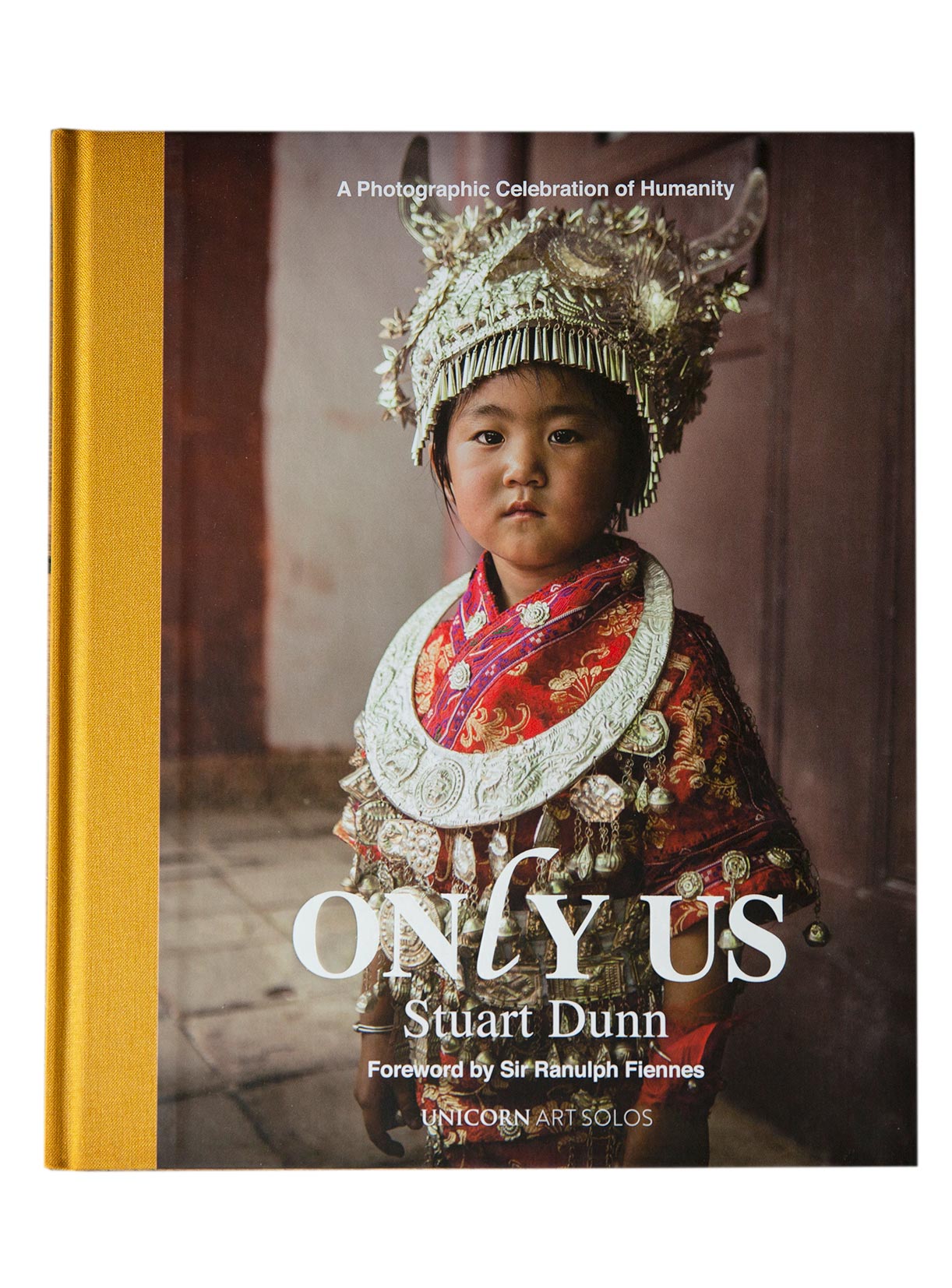

In the foreword to his new book, Dunn argues that humankind’s hopes, fears, flaws and desires are common to all. For him, ‘us’ and ‘them’ doesn’t exist; there is ‘only us’ – and those last two words form the title of the book. Chronicling Dunn’s years spent traveling the world, this is an epic photographic portrait of humanity featuring a diverse cast of characters.

You can find out more about Stuart and his work on his website, and we were pleased for the opportunity to sit down and chat with him.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

01. How did you get into photography?

Shortly after I left art college, an opportunity arose to travel South Africa with a friend. I took what little money I had and jumped at the chance. While I was there, I took photos – none of which were any good – of the people and the animals I encountered. Then one evening in Durban, I was involved in a car accident, and my friends and I had to go to the police station to give statements.

While I was sitting in reception, a huge police officer came lumbering through the door, pushing a local man in handcuffs ahead of him. Luckily, I had my little 35mm camera in hand and asked the officer if he’d mind if I took his photograph. He answered: “No problem, but wait: I’ll get him to smile for you.” He proceeded to twist the man’s arms behind his back, causing the man to scream in pain. I raised the camera to my eye and took the shot. That was the first time I realized that the camera was more than just a device for taking holiday snaps. Photography was a tool for something much more profound.

02. What attracted you to travel photography, and why do you concentrate on photographing people?

A simple answer would be to say that I love to travel and I love photography: why not combine the two? I guess the truth is much more complex. For me the two are inextricably linked. My love, curiosity and fascination with people is deep-rooted. I can’t help but look at a person and think: “What is their life like? What would it be like to be them?”

I want my photography to convey that sense of curiosity and wonder I feel when I first meet a person

And I’m not just talking about indigenous people I’ve met in the Amazon, for example: the same is true of a businessman on the Tube at 9pm coming home from work. What makes a person tick? What are their hopes, their fears, dreams and aspirations? Are we the same? Ultimately, I want my photography to convey that sense of curiosity and wonder I feel when I first meet a person.

03. Do you ever shoot landscapes in these amazing places?

I’m quite fond of shooting panoramas while I’m on location. In some ways, they are more for me personally. They help document the landscape in a way that is more akin to the way we view and soak in an environment. But I’ve got to be honest: even with my landscapes, I’ll try to sneak in a person in as a focal point or to give it scale.

04. What has influenced your photography?

I’m a huge photography fan, with many influences old and new. The most inspiring figures for me would have to be Robert Frank, Fan Ho and Steve McCurry. Robert Frank for his rawness and honesty. Ho Fan’s work is incredible. Beautiful black-and-white compositions, back-lit portraits, shafts of light, minimalist silhouettes, smoky back streets: you name it, it’s all there in his work.

If I’m honest, it took me a little while to really appreciate Steve McCurry’s work. I always respected him as a photographer, but it has been over time, looking at his more intimate photography, that I have really learnt to appreciate what a talented photographer he is.

05. What was the first camera you used?

A little Hanimex 35mm compact my parents bought me. My first proper camera, in my mind, was a Canon EOS 500N. I’d saved up for months and bought it second-hand from a local photography shop. For many years, I took some great shots using this camera, some of which still stand up and are in my Only Us book.

My first digital camera was a Canon EOS 20D. I remember thinking how clean the images were. I was so used to seeing grain in my photos; to then have this camera with such incredible resolution and lack of noise was a revelation.

I’ve used them for so long now I don’t actually need to think while using Canon cameras or lenses. They have become an extension of myself, and my focus is on the content not the tools – the way it should be.

06. Which lenses do you use?

All of my lenses are Canon L-series. I’ve taken them to the Arctic, the Amazon and the Sahara many times over, and they have never failed me. I’ve done terrible things to my equipment, things that kit should not have to go through, and it all just keeps on working.

My standard setup, which I take on every trip, comprises the 16-35mm f/2.8, the 24-70mm f/2.8 and the 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6. I also have a 100mm L-series macro lens and a 24mm tilt-and-shift.

07. Do you have a go-to lens – something that you leave on the camera most of the time?

While zoom lenses will always have their place, I tend to gravitate towards a 50mm or an 85mm for my portrait work. My camera will usually sit in the bag with a 50mm Zeiss Milvus f/1.4 attached.

My camera will usually sit in the bag with a 50mm Zeiss Milvus f/1.4 attached

Zeiss lenses are quite heavy, manual-focus and generally quite difficult to work with; but the results they deliver, if you’re prepared to put in the hard work, are simply beautiful. They are not necessarily the sharpest lenses on the market, but they have a gorgeous aesthetic and a softness that feels very natural to me.

08. What are the main differences between shooting video and still photographs?

A documentary film is made up of a collection of sequences or scenes, and I am always thinking about ‘the sequence’. How will a collection of moving images flow to tell a story and inform the viewer about how they should be feeling? The important thing for me is to represent my subject truthfully. In that sense, my still photography and my filmmaking are grounded together by the same foundations.

Obviously, there are physical differences between cinematography and photography. The equipment used to make a documentary has got completely out of hand. On a recent shoot in the Congo, we had around 60 cases of camera equipment! We are using the same tech as Hollywood feature films these days to shoot a documentary. Drones, gimbals, sliders and lights all play a vital role.

09. Do you have any advice for any of our readers who want to take better travel portraits?

Don’t get bogged down with kit. Too many lenses, tripods and flashes can drag you down. The amount of kit you carry is directly linked to the number of miles you can hike, and the energy you can put in when something interesting presents itself.

Try heading out with a small discreet bag, with nothing more than a 24-70mm attached. There’s not much you can’t do with that lens, and you’ll be amazed how much more you will get out of your day.

The amount of kit you carry is directly linked to the number of miles you can hike

Be brave, don’t be scared to talk to people. Strike up a conversation, show some interest. Don’t just ‘take’ their photograph, let them give it. You’d be surprised how many incredibly interesting situations I’ve got myself into just through talking to people.

10. What would you say to anyone traveling to a place for the very first time?

It can be a daunting experience. You ever quite know how people will react to your camera and presence. Some parts of the world are a photographer’s dream, while others can turn perilous at the mere sight of a camera being pulled out of a bag.

The chaos of being somewhere new can be quite overwhelming: your senses are overloaded, and often you don’t know where to begin. Obviously, unexpected encounters can be incredibly special, but I like to have an idea of what I’m trying to achieve before setting off. Then at least I have a starting point. It sounds ridiculous, but I have an imaginary collection of beautiful compositions taken in perfect light, floating around my head, that I haven’t actually taken yet.

11. Are there any places that you enjoy returning to?

The Arctic will always hold a special place in my heart. It’s a hostile, barren place that is incredibly difficult to operate in, but the rewards are worth it. The light quality there is unparalleled. It has a clarity and crispness I don’t think I’ve seen anywhere else in the world. However, during the dark season it can also be a dark and foreboding place, requiring very long exposures to get anything out of your camera.

I also love the minimalist landscape. On some days, it’s like nature has given you no choice but to photograph in monochrome.

12. What advice would you give a stills shooter looking to become a filmmaker?

What do you want to film? If you want to be a wildlife filmmaker, you need to get out there and start filming animals. Nobody is going to send you an expedition to Africa to film elephants if you haven’t done it before.

For a body of work to have weight and substance, you have to maintain a certain level of continuity

The client or broadcaster want to know their budget is in safe hands, and that you can deliver the project you have been assigned. And therein lies the problem. How do you gain the opportunity to film something you have no previous experience of? You may need to get creative and self-fund a filming trip to build a showreel and earn a potential client’s trust.

13. You come back from assignments with great images, but how is your work so consistent?

Consistency is the hard part. For me there have to be rules: a set of guidelines and a standard I set myself. For a body of work to have weight and substance, you have to maintain a certain level of continuity. It’s not easy, but it certainly makes a project more interesting. Often a portfolio or a collection of images will start with an idea, a style or a theme, which I can then capitalize on and carry forward through the rest of the assignment. Once you’ve set your style, then it’s all about sticking to it.

About the book

Only Us: A Photographic Celebration of Humanity by Stuart Dunn, with a foreword by Sir Ranulph Fiennes, is published by Unicorn: www.unicornpublishing.org

Read more:

Best lens for travel photography

Best lens for portraits

Best camera for portraits

Alistair is the Features Editor of Digital Camera magazine, and has worked as a professional photographer and video producer.