New book captures London’s “era-defining” late-1980s club culture

Photographer Dave Swindells’ record of the nascent acid house scene will become the classic visual account of the times

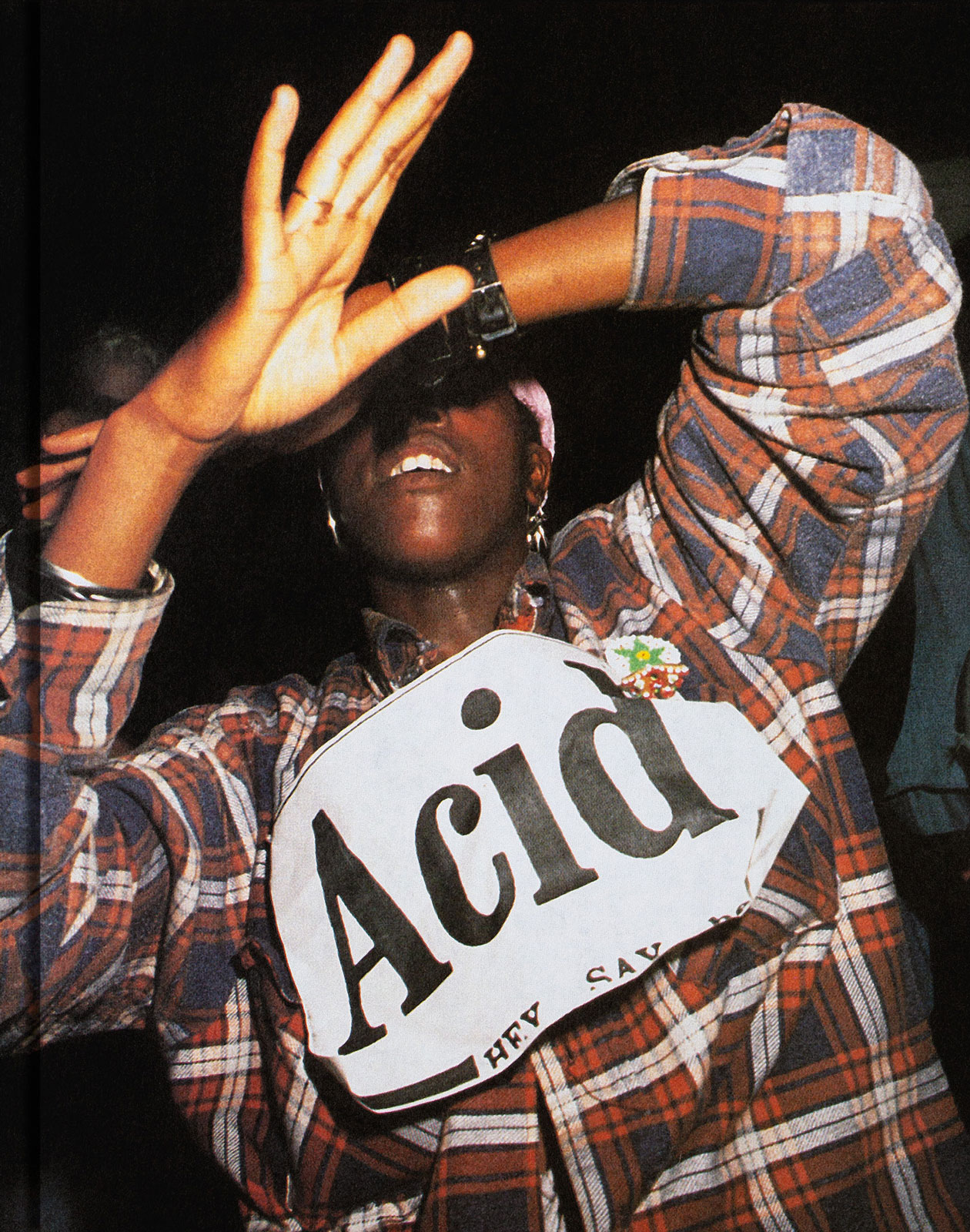

The most significant youth movement to happen in Britain since punk in the 1970s – the acid house explosion of the late 1980s – created a musical culture that still endures today.

DJs and musicians who were there at the beginning still play to large audiences around the world, and several global mega-music festivals owe a debt to the can-do ethos and visual aesthetic of the UK’s early acid house parties.

Taking place three decades before the arrival of social media, one of the definitive pictorial documents of the scene was captured by Dave Swindells, then the nightlife editor of London’s Time Out magazine.

As a new collection of his images appears in his latest book, we found out more about those heady days – and the challenges of getting it all on film – from a man who was there…

Was your route into this kind of photography to provide some photos for the nightlife section you compiled for Time Out magazine?

I’d first started taking nightlife photos at one or two of my brother’s club and warehouse party events in London in 1983.

I was studying English Literature in Sheffield, but my brother Steve had been one of the early ‘one-nighter’ club promoters hosting clubs like The Lift and Jungle, which were polysexual before that word was invented. Most of those early photos were rubbish, as it took time for me to learn how to use flash and take photos after dark.

I moved to London in 1984, but through my brother (again) I got a job working behind the bar at Fouberts in Soho and later at The Embassy in Old Bond Street.

Eventually I got fired after being caught taking photos when I was supposed to be collecting glasses, but by then I’d approached i-D magazine and started doing photos for them, so I was back at The Embassy a couple of weeks later to take pictures.

Was Shoom the first of these Ibiza-inspired events you went to, and did you come away thinking it could be the start of something big?

No, it was actually Future, Paul Oakenfold’s club night. I’d already been hearing exciting stories about Shoom, so once I’d experienced the carefree abandon of the dancers at Future, I made sure that I went to Shoom on the following Saturday.

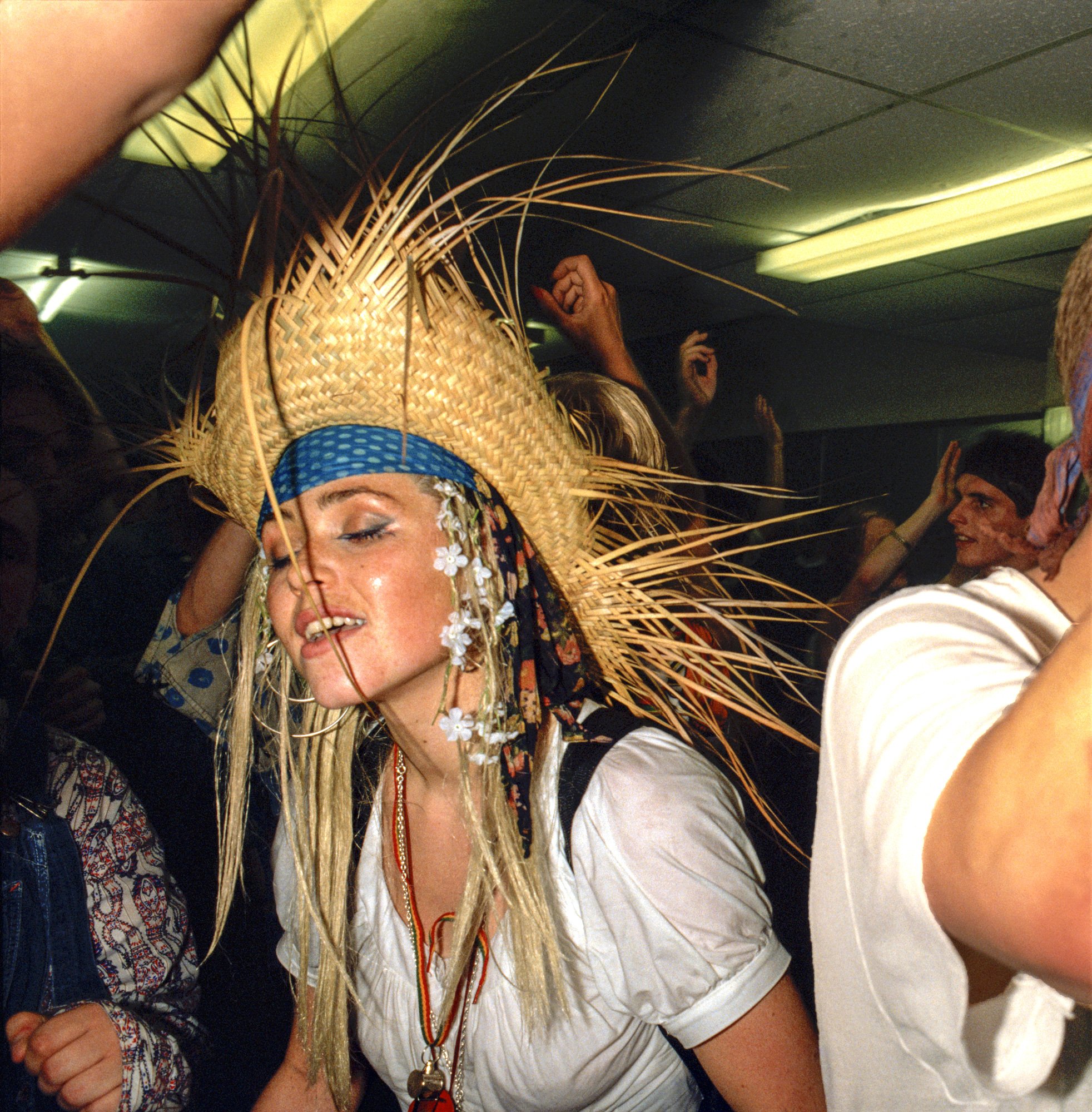

The atmosphere there lived up to what I’d been told, and at the same time there was so much great house (and Balearic Beats) music that had hardly been played in London.

Clubbers were dressing to dance in baggy tops, Smiley T-shirts, dungarees and Converse trainers, so there was already a new look, too. It had all the ingredients to be era-defining.

What was your camera and lens setup around that time, and which films did you favour using?

By 1988 I was using a Canon A-1 SLR with 50mm and 28mm wide-angle lenses. Mostly I used the wide-angle lens to get in close and be part of the action, with a simple wide-angle diffuser on the flash to spread the light.

I had a cord so that I could use the flash off-camera, as I preferred more directional lighting. I wanted to include as much ambient light as possible, so I used to vary the exposure time up to a couple of seconds. It was basically guesswork, so of course it didn’t always work, but the multiple strobe flashes could add to the drama of the image.

I liked using Fuji slide film and during that year there were one or two events where there was enough light to dispense with the flash and use 1600 ISO fast film.

Shoom was held in a basement and because it was so hot, you once said that it would take half an hour for the camera to warm up to the temperature of the room. Was this just one of the technical challenges you faced?

The heat and humidity were intense, but fortunately I’d been to soul weekender events before so I knew that the camera body just needed time to warm up to room temperature, and I usually carried a couple of lens cloths, too.

Once the camera was ready to use I had to hope that they weren’t about to blast a lot more smoke into the room, and that the strobe light wouldn’t be on incessantly.

There was rarely enough light to focus, so I used white marker pens to highlight the 1m and 3m distance indicators on the lens, and if there was UV light, that worked really well.

Are there any photos from those times that particularly stand out for you, that can take you right back to a particular time and place?

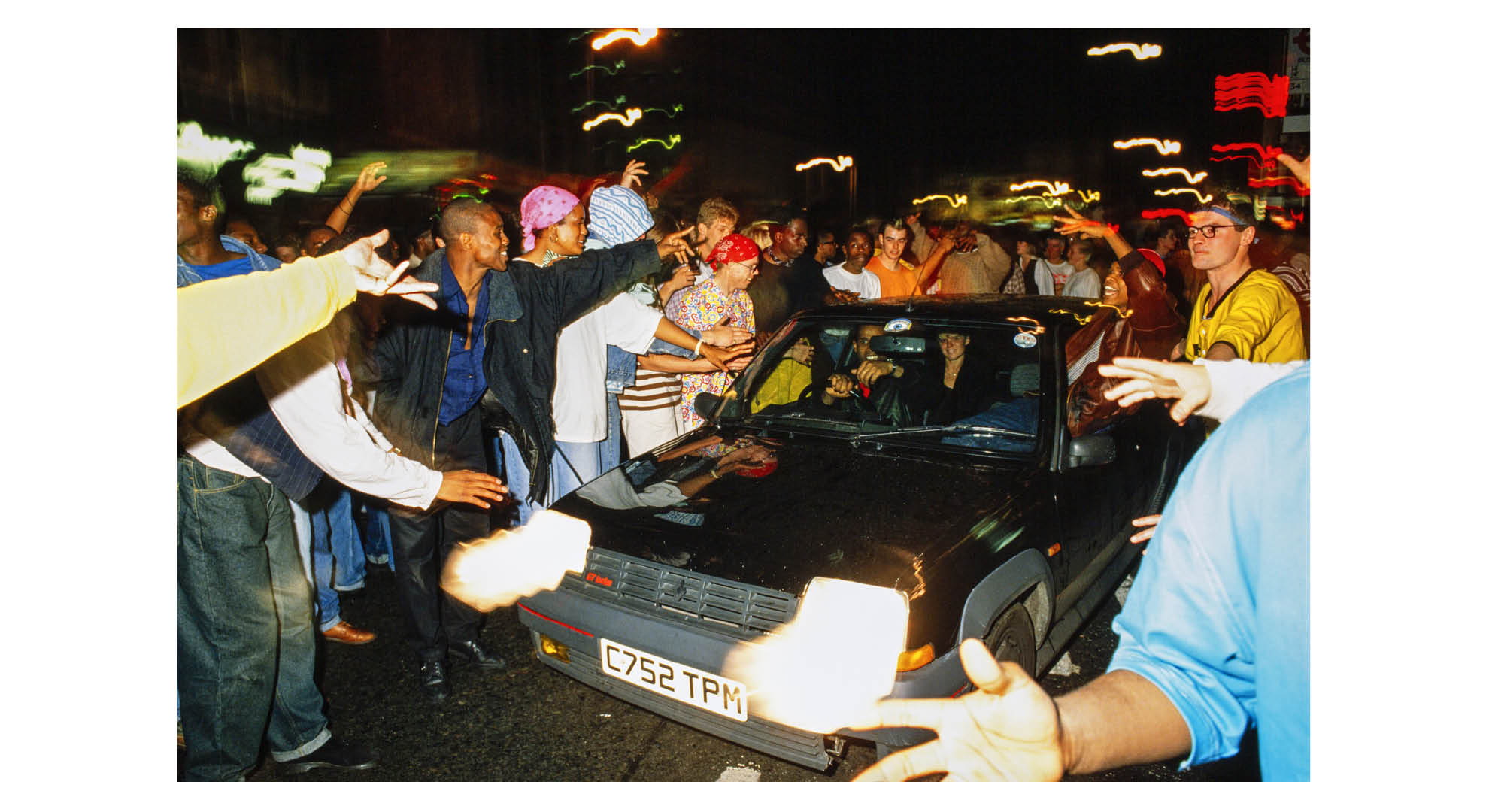

The most obvious stand-out shots are the street party photos, because in those moments the energy and euphoria of acid house couldn’t be contained in the clubs.

The street parties happened on the Strand and in Trafalgar Square (after Spectrum at Heaven) as well as on Tottenham Court Road after the Trip, and in a way they were a precursor to the massive raves in fields and aircraft hangars that happened in the summer of 1989 as the scene expanded out from the cities.

Did you ever leave your camera under the turntables and get fully involved in the fun, or did you have to be a total professional at all times?

I often danced while carrying the camera, which I thought was a totally pro thing to do [laughs], or I’d sit the camera on top of the bag and dance around that if the music demanded it, partly because as a photographer you don’t want to be a total pest, blinding people with the flash all the time.

With the luxury of instant digital image previews not available to you on film cameras in the late 1980s, you must have been on the top of your game when it came to judging exposure and using flash. Had you studied photography formally?

The lighting in clubs could change all the time, but by 1988 I’d been getting fairly reliable results for about three years, and because I was shooting regularly it meant that it worked more often than not.

I didn’t study photography, but I learned how to develop and print as part of a photography club at university, and the rest was down to trial and error.

You tend not to see the errors, but thanks to Photoshop (other software is available, of course) pictures that were horribly over-exposed can be made to work 30-odd years later!

In the book there are photos from a night at Future, which were taken in black and white so that you could meet a Time Out magazine print deadline. Did you include these images because they have so much impact?

I only shot in black and white at Future because at that time it was necessary to get a negative made before a colour slide could be printed in black and white in the magazine, and of course that took time.

I wanted those shots to be in the following week’s issue so I shot a roll of Ilford FP4 that night.

I really like black and white and I love the drama of those Future shots, but subsequently I wanted to photograph in colour because it was a really colourful scene.

The popularity of the acid house story meant that during that summer I was sending the slides to Sweden and Spain, France and Germany, and that’s probably why quite a few got lost.

Your photography from the nascent acid house scene has been widely used in books about the period – how satisfying is it to have documented such a pivotal moment in our youth culture, and done it so well, too?

For quite a while I wasn’t really satisfied about it, because I only seemed to be recognised for the acid house and rave pictures, although I had photographed so many other scenes and styles over 30 years.

But of course, it’s lucky to be recognised at all, and in this book I wanted to bring together the photos I had and include many shots that hadn’t previously been published, while also ‘reclaiming’ photos from old magazine tear-sheets (where the original slide had been lost), so I photographed the magazine tear-sheet.

As an aside, like a lot of photographers, I prefer photographing slides with a 1:1 macro lens rather than using a flatbed scanner, as the quality is better.

Are you still taking photos of club events and festivals?

The last rave I photographed was in 2018 and that was using a Mamiya 6 medium-format film camera, which is the way I’d be likely to go now in order to shoot more portrait-style photos.

Has the Instagram generation and the quality of the cameras in everyone’s pocket made club photographers less relevant now?

There’s still a place for candid photography at events, but it’s harder to shoot when so many people want to control the way that their image appears, sometimes even grabbing the camera to delete images that they don’t like. That’s not photography, it’s public relations.

Acid House As It Happened by Dave Swindells is published by IDEA Books, and is priced £50.

Read more

Tips for photographing live music

Make money with your camera

The best photo printing online

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Niall is the editor of Digital Camera Magazine, and has been shooting on interchangeable lens cameras for over 20 years, and on various point-and-shoot models for years before that.

Working alongside professional photographers for many years as a jobbing journalist gave Niall the curiosity to also start working on the other side of the lens. These days his favored shooting subjects include wildlife, travel and street photography, and he also enjoys dabbling with studio still life.

On the site you will see him writing photographer profiles, asking questions for Q&As and interviews, reporting on the latest and most noteworthy photography competitions, and sharing his knowledge on website building.