Self-publishing books is the way forward, says top wildlife photographer Doug Allan

Retain control and you’ll create “something special”, reveals long-time colleague of Sir David Attenborough

One of the headline speakers at The Photography Show Virtual Festival in September, Doug Allan has worked for leading international broadcasters including the BBC, National Geographic, Discovery Channel and Netflix, contributing to The Blue Planet, Planet Earth, Frozen Planet and more.

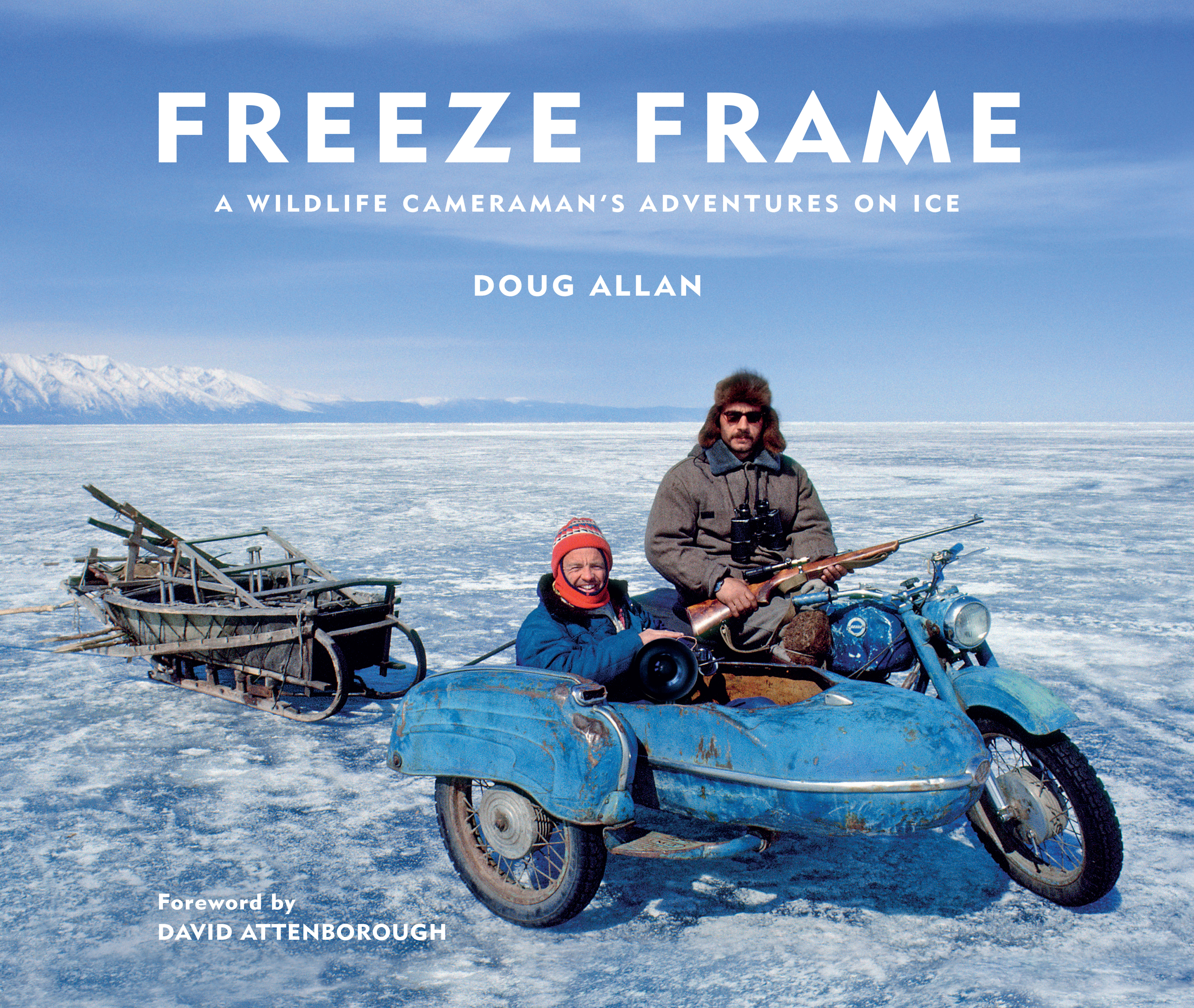

Doug’s book Freeze Frame features stories from his life as a cameraman and includes a foreword from the legendary naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough.

At The Photography Show Virtual Festival, we asked Doug about how he made the transition from diver to wildlife photographer, and the skills and qualities required to remain a successful camera operator for big wildlife series over three decades.

Here’s a taste of what Doug revealed; read a longer version in issue 236 of Digital Camera magazine, which is on sale now priced £6.99/$14.99/AUS $15.99.

How did you make the move from being a diver to a photographer?

I was 24 when I first went to the British Antarctic Survey’s research station on Signy Island, and I’d describe the eight years down south that followed as my formative years.

In the summer at Signy, there would be 20 to 25 people on the base, but in the winter, when the ships went north and the sea ice formed, it would only be about 15.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

As a diver, I was one of the support staff; my job was to make sure that the marine biologists dived safely and efficiently.

For me at that time in my life, it was near perfect. I learned a lot about cold-water diving, as well as how to manage in the cold topside. l came to know my own limits; the difference between feeling chilly, approaching hypothermia, and being frostbitten. It gave me a feeling for snow and ice that I took on into my filming career.

I became interested in photography while in the Antarctic, starting with stills. I wanted not just to photograph the wildlife, but also to cover the whole story about how the base operated – so I learned how to take the kinds of photographs that would tell those stories. It was almost like training to be a photojournalist rather than a wildlife photographer.

Some of those pictures are among my most valuable today, in terms of giving talks and showing people how life was on the base back then.

And the talks you give were pivotal in you deciding to write your own book, Freeze Frame: A Wildlife Cameraman’s Adventures on Ice. Can you tell us how it came together, and why you decided to self-publish it?

I was doing a lot of public speaking and thought how satisfying it would be to bring together a collection of stills in a book, rather than having disparate short articles or selling individual images. In my book, I could answer the questions that people often asked me.

I did consider doing a “proper” autobiography but to be honest when I read what I was writing, it was boring. And I was the author. I remember sitting bolt upright one night and thinking why not just write about my life in short stories – they could be 200 words, if that was appropriate, or 1,500 if there was more to say. I could go straight into them and could cover all the questions that people ask me, and could also put in little details that I hadn’t had the chance to explain before.

I saw it as part natural history, part life story, insights into what makes us tick behind the camera and a range of personal stories, from my roots in the Antarctic to my most recent shoot.

The other decision was to do it as a self-published book. I’d looked at enough books about photography to know that I didn’t want pages of small pictures separated by pages of text. I wanted it more integrated. Into the frame came my good friend the brilliant book designer Simon Bishop.

Simon showed me some books that he had done, and it was clear he and I were on the same wavelength for the “look” of the book. As for the words, I had done several pieces for Roz Kidman Cox, formerly the editor of BBC Wildlife magazine, and when it came to writing style we were in agreement too.

So I opted to self-publish the book with the help of Simon and Roz, and that was a great decision. I realised that had I gone to a publisher to sell them on the idea, from that point forward I would lose control over the content, the style and design. With Simon, Roz and I working together, we produced something special.

Self-publishing, however, also meant I had to take charge of the distribution. It cost me £28,000 [$36,500 at today's exchange rate] for the first 3,500 copies – that included paying Simon and Ros, a graphic designer for the maps, Stephen Johnson for colouring, and the printing itself. Images and my time came for free.

I sold those 3,500 or so within 18 months and have been printing about 1,000-1,500 every year or so since then – to date I’ve sold 12,000 copies. I wouldn’t have sold so many had I not done so many talks, but it’s been a very successful commercial enterprise. And it’s still really satisfying – I love the feedback from people when I open a copy to sign it for them.

• The best photo book services in 2020

The book includes a mix of film and digital images. How different was it using film, compared with today’s digital equipment?

It was massively different. With film, there was no feedback on what you had actually shot. You had to hope that you had everything, hope it was OK technically, and hope that the film wasn’t X-rayed on its way back to the UK. You’d do the filming, come back and hand the film in to the labs.

A couple of weeks later, the producer would call you in to see the rushes [the footage as it came out of the camera]. In the projection room, it would all be up on a big screen, with the editor on one side of you and the producer on the other. You waited for the big intake of breath – and hoped that it wasn’t because you’d lost focus in some crucial shot, but because they’d really liked what you’d done.

Is that conceivable to people who’ve grown up with the instant feedback of digital?

When I went to the Antarctic to do the emperor penguins, and then later on three films for [the ITV series] Survival, I effectively shot blind through the winter. It wasn’t until I came back to the UK and all the film was processed that I could see we actually had a movie in our hands.

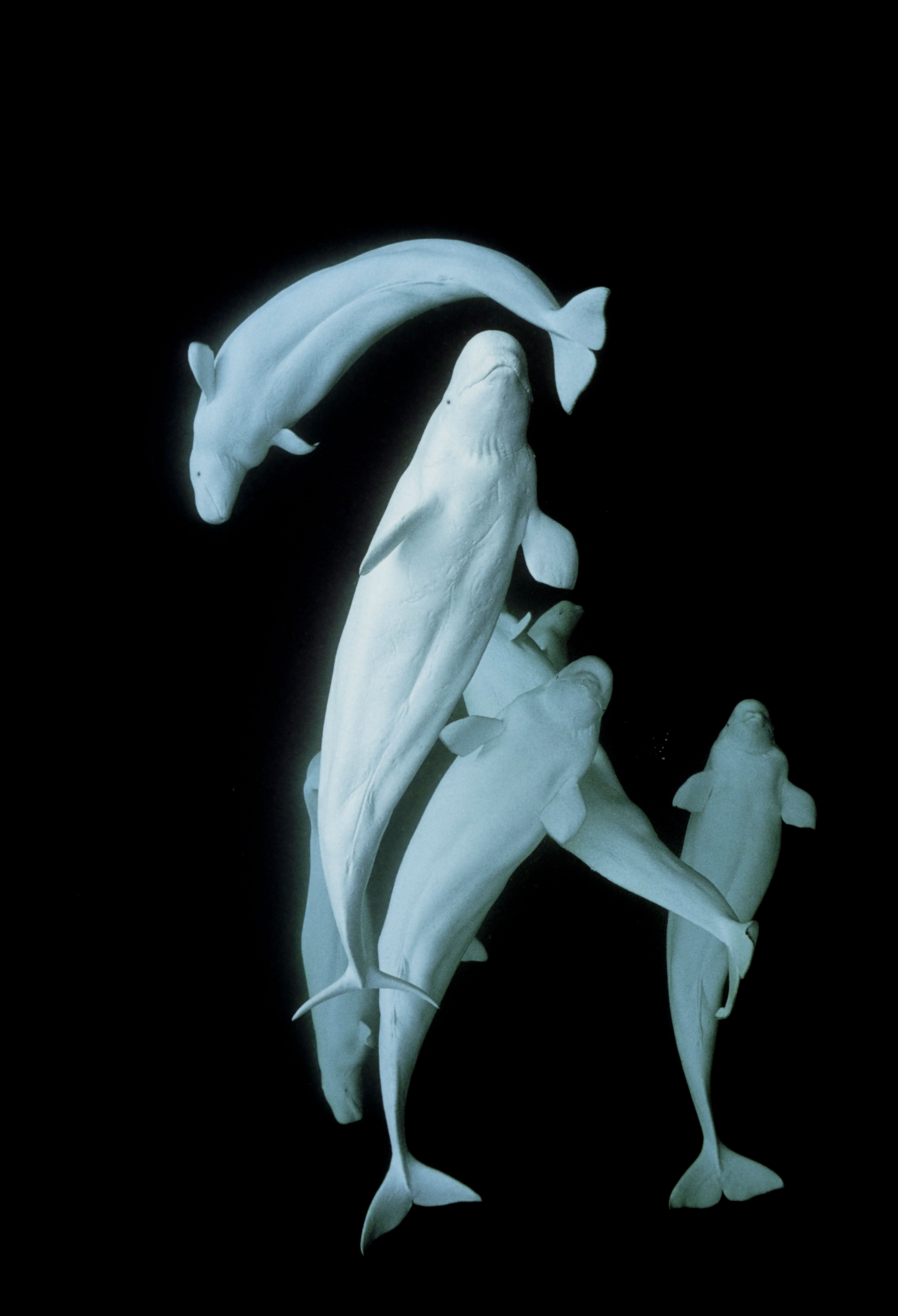

Underwater the problems were even greater… Imagine you dive, and you’ve got 36 pictures or 10 minutes of film. You shoot your 10 minutes, return to the surface, split the housing, open up the camera, load a new film and go back down again – the chances of re-finding what you had been witnessing are small.

And we’d be doing all this through a small optical viewfinder that was quite dark at small apertures. To go on to one-hour tapes with a lovely big bright monitor was massively better than shooting on film. Electronic imaging also had that ability to penetrate murky waters, to give you sharp edges and much better colour than film straight out of the camera. Moving to electronic media was a huge step up from film, and it was an even bigger improvement for working underwater.

Having said that, only the last couple of generations of cameras are producing better results electronically than you could get on fine-grain film. Plus, shooting on film is almost future-proof: that film will always be accessible.

Shooting on electronic formats – well, hard drives and memory cards haven’t been around long enough for us to know how they will last. And early electronic formats can pose real problems for modern incompatible software.

Freeze Frame by Doug Allan is available for £25 plus postage, from dougallan.com. To add a personal dedication, write to: dougallancamera@mac.com

• A longer version of this interview appears in issue 236 of Digital Camera magazine, which is on sale now priced £6.99/$14.99/AUS $15.99.

You can buy the current issue of Digital Camera magazine in print at our Magazines Direct secure store.

To make sure of your copy every month, subscribe at our online shop from just £12.50!

Alternatively, there is a range of different digital options available, including:

• Apple app (for iPad or iPhone)

• Zinio app (multi-platform app for desktop or smartphone)

• PocketMags (multi-platform app for desktop or smartphone)

• Readly (digital magazine all-you-can-eat subscription service)

Read more:

5 wildlife and nature photography tips

10 ultimate locations for wildlife photographers

Photography courses and holidays: how to choose the right one for you

Niall is the editor of Digital Camera Magazine, and has been shooting on interchangeable lens cameras for over 20 years, and on various point-and-shoot models for years before that.

Working alongside professional photographers for many years as a jobbing journalist gave Niall the curiosity to also start working on the other side of the lens. These days his favored shooting subjects include wildlife, travel and street photography, and he also enjoys dabbling with studio still life.

On the site you will see him writing photographer profiles, asking questions for Q&As and interviews, reporting on the latest and most noteworthy photography competitions, and sharing his knowledge on website building.