Stop moaning… drone pilots were wrong to complain about regulations

Many drone operators were angered by increased regulation, but in the end we got better drones and flying opportunities

Many drone operators have been angered by regulations in the USA and EU/UK, but looking back lets us see how the ultimate outcome might, finally, be better drones and flying opportunities.

The arrival of consumer quadcopter-style drones began in earnest in 2010 when Parrot demonstrated the AR.Drone at CES, a quadcopter with a camera that could be controlled by an App on an iPhone (the App store was itself not yet two years old).

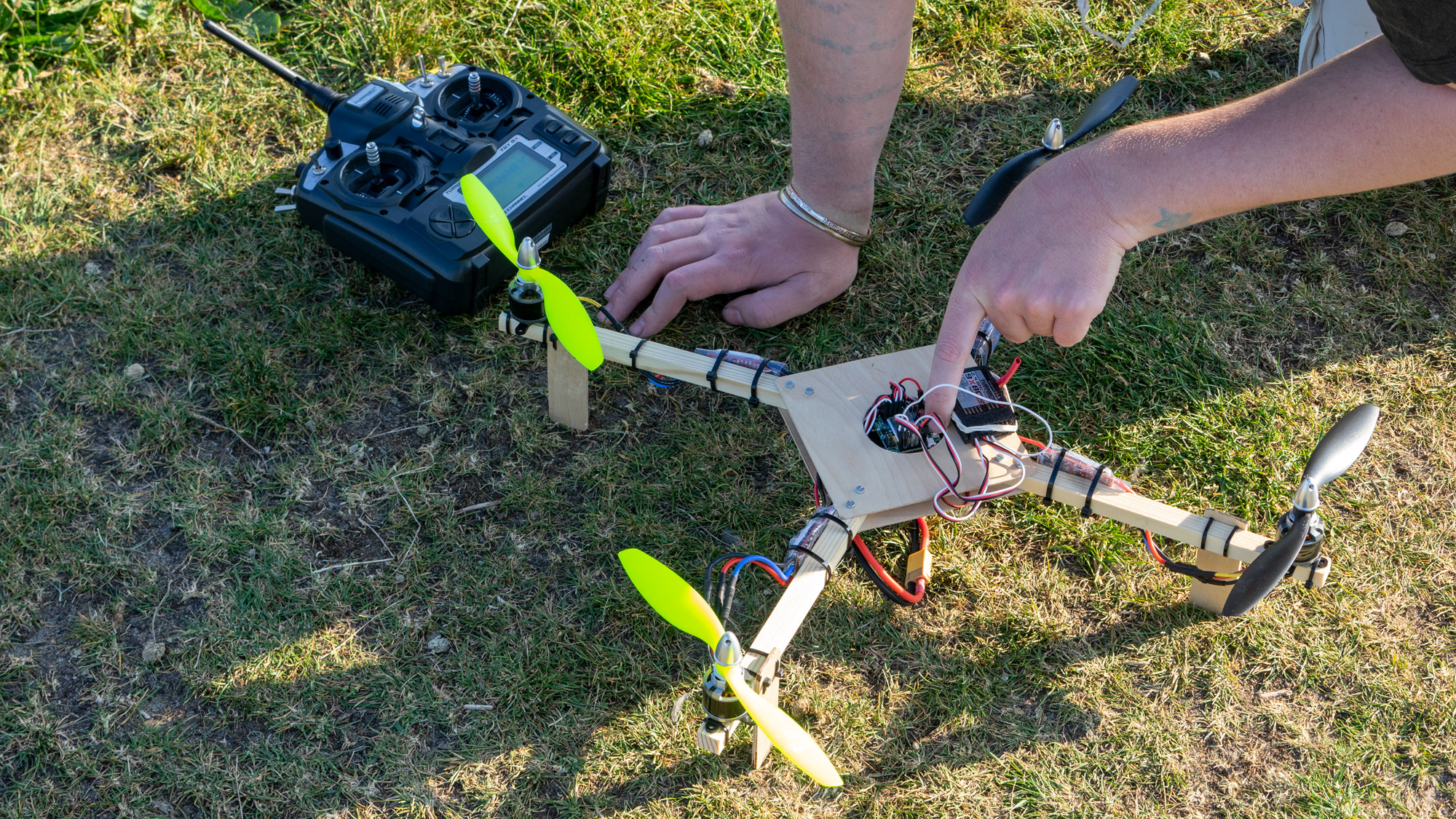

Suddenly all the elements needed were there; public attention, a consumer-friendly product, a live video feed, and the ability to hover and record. This was just the tip of the iceberg; enthusiasts could buy components to build their own drones from a rapidly expanding market of component suppliers. There was no way the skies could remain the domain of full-sized aircraft and a few model aircraft pilots.

The existing legislation, however, wasn’t built to cope with the speed of change and what was a novelty for some quickly became an area of concern. Enthusiasts were able to come together at events and self-regulate, but widespread consumer use made that approach unworkable.

The Era of regulation Begins

As it happened, rules did already exist. In 1936 in the USA the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) laid down a safety code over 2 decades before the FAA was created. The code has been followed since, with only additional FAA advisory (AC 91-57) in 1981.

In the UK, the BMFA from even earlier – 1922, in fact, making this the centenary year of organized model flying. The UK’s governing body, the Civil Aviation Authority, stepped in in 2012 and 2013 to emphasize a direct visual line of sight rule.

Drones above 20Kg (44lb) were expected to sense and avoid others (heralding technology we know and love in much lighter drones now). Those under 20kg were still to be operated at least 150m from a congested area and – if commercial – a qualification was needed with an in-person exam.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

In the USA a 55lb limit had been the criterion for applying for FAA airworthiness certificate for the drone itself, but the significance of lighter categories was acknowledged with the

registration program for drone pilots – civil or commercial – above just 250g (8.8oz) which came into force in 2015. Australia is among many other countries to have introduced a 250g limit or tier.

This weight limit – and the knowledge something similar was pending in Europe – didn’t endear aviation authorities to established drone pilots. Despite even the most committed operator having at best half a decade in the game, no one was pleased about the speed limitations that seemed to be arriving. At the same time, there was already some nostalgia for the early days and, inevitably, some mourned the arrival of polished commercial products like the Phantom and Inspire from DJI.

2018: The Year of Dronemageddon

Then in 2018 there were two serious incidents and one terrifying piece of research from the University of Dayton which kept eyes firmly on the risks. The researchers made plain how much damage a then-typical drone, the Phantom, would do in a collision with a wing at flight speed (and that without fuel inside) with a widely distributed slow-motion video. With memories of the harm birds can do in the collective conscious thanks to the 2016 movie of “Miracle on the Hudson,” Sully, this only served to exaggerate worries about drones.

Drone vs Plane, crash test video - DJI Phantom quadcopter drone and small plane wing

On 4th August in Caracas, Venezuela, two drones carrying explosives were flow near President Maduro as he gave a speech. One detonated, and several guardsmen were injured, while the other crashed into an apartment building. There is a good deal of doubt about the credibility of some details (not least because the president was in the habit of claiming terrorists were attacking him) but many found the story credible which tells us all we need to know about the fear of drones at the time.

Finally, there was the Gatwick incident. Between December 19-21, 2018, the UK’s second largest airport was intermittently shut down when drones were reportedly seen, first by a security officer and then – after the news got out – by many individuals. There are plenty who argue that there weren’t any drones. Certainly there is no conclusive evidence despite all the TV crews present for the second and third day. Not only that but police ended up having to pay out £200,000 for wrongful arrests. What is inarguable, though, is the fear of drones which airport radar never saw shut down a major airport for days, and cost airlines £50 million (US$64 million).

Why weren’t drones banned?

In the light of 2018, and general security concerns, it’s not impossible to imagine a flat ban on drones, or at least a very restrictive testing regime coming into force. Instead the 250g restriction made its way to Europe alongside a similar registration requirement which takes place online and includes a basic test. (Since Brexit, the UK’s CAA has followed the regulation strategy set out by EASA regulations, so have the same broad rules. As a non-member state, however, qualifications obtained in the UK aren’t valid in the EU).

Europe introduced a more defined range of tiers than in the USA, but they’re relevant to drone customers everywhere – the size of the European market means international firms like DJI will certainly have checked the specs (just as American and UK iPhones are likely to get USB-C chargers when EU Anti-Trust rules come in).

| Header Cell - Column 0 | Weight | Speed limit | ADS-B required? | GPS needed | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | Under 250g | 19 m/s | No | No | A1 |

| C1 | Under 900g | 19 m/s | Yes | Yes | A1 |

| C2 | Under 4kg | - | Yes | Yes | A2, A3 |

| C3 | Under 25kg | - | Yes | Yes | A3 |

| C4 | Under 25kg | - | No | No | A3 |

That’s not all; some must come with low-speed modes which the pilot can chose when flying near people. These rules apply to new drones with the category mark after 1st 2023 – the Mavic 3 was the first drone to be certified under the scheme. The subcategories are the areas flight is allowed in and are essentially:

A1: Over people

A2: Near people (an A2 Certification exam must be passed)

A3: Flying far from people

The A2 ‘Certificate of Competence’ can be sat online but costs around £100 for a video course – still within reach of consumers, but definitely an irritation which will put many off. Going past that requires the more involved GVC qualification and the creation of operating procedures.

The clear upshot of all this is a strong incentive for all major manufacturers as well as Australia, to cater to the sub 250g market. This was a weight that catered exclusively to toys when these rules were first being discussed by worried enthusiasts.

It can be done

In October 2019 DJI announced the 249g Mavic Mini – an achievement so significant the weight was emblazoned on the side of the drone. It effectively replaced the 300g ‘Spark’ as a consumer entry point, while still including a camera with gimbal which could capture 1080P video.

DJI hasn’t stopped there; the higher-end Mavic 3 Cine sneaks in 1 gram under the C1 900g limit while both DJI and Autel have also crammed a 4K camera, subject tracking and collision sensors in sub-250g drones in the EVO Nano and Mini 3 Pro (see our DJI Mini 3 Pro review). More subtly, flying these drones makes plain how well modern processors handle and compensate for wind despite the low weight; you can fly it in speeds of up to 22mph without worry – less than the 27 the Mavic 3 can handle but these are conservative figures and people have tested them in significantly worse.

The heaviest mainstream drone a prosumer can comfortably pilot is the DJI Inspire 2, with a take-off weight of 3.44kg to 4.25kg. Launching in 2016 this predates the European rules, but there are persistent rumors of an impending update. If so, surely DJI will want to shave 250g off the maximum take-off weight to pick up a European C2 certification? Lower weight would certainly be appreciated by anyone who has carried a DJI Inspire 2!

It’ll be interesting to see though; there is a worse scenario for Europeans (including UK): the Mini 3 Pro’s larger Battery Plus isn’t on sale in Europe – presumably, because it would push it into the C1. That’s because the category applies to the device, and the potential maximum take-off weight would be over 250g. By preventing the sale of the batteries, DJI can safely apply for C0 certification. Perhaps this kind of issue could rule out some Inspire 3 features in Europe?

But for the rest of the world such pedantry doesn’t impact on the possibilities – you can buy the heavier battery, or not, and make your own choice. In this way markets outside the Europe have benefited from the weight restrictions while still gaining flexibility.

Regulations don’t please everyone

Perhaps not. Everyone, including the self-build market is also being threatened by has also been required to add ADS-B or Remote ID by the FAA unless flying in a special free area (FRIA). This technology is a bit like a local Apple AirTag that can be interrogated by anyone near the aircraft (enforcers, other aircraft etc). It also forces GPS onto all drones – not something FPV pilots traditionally wanted or needed – because the take-off location is part of the Remote ID broadcast signal. (It also necessitates the tech and antenna to make the broadcast.)

For DJI customers and the like, this isn’t going to be difficult; the firm takes care of it for them. But if you’re building an FPV drone there is some debate looking for a niche device to add this compliance the costs will likely be high. It does push pilots toward the big firms rather than preparing their own compliance. Some are estimating this module will cost $250 per drone, and the FPV Freedom Coalition isn’t happy about privacy concerns either.

It seems a bit invasive – and has many screaming about privacy – but it does also provide a basic framework by which authorities can relax about drone use, which in turn creates opportunities for serious users.

A win for content creators, at least?

Broadly, yes. Where we need FPV-like footage, we now have options from DJI which do meet the regulations and bring the ease-of-use which (if most of us are honest) is preferable to the achievement of a self-build. At the same time the major brands – DJI and Autel in particular – have made the restrictions pale into the background and allowed us to enjoy the convenience of more portable devices.

The same features and processing power which might be thought of as safety-focused also help the drones achieve automated tracking, while cameras with sensors of 1-inch and bigger can be had

It's even fair to argue that the simple online tests and entry fees of under $200 make the commercial entry – at least for many uses, if not all – lower than we saw before, meaning photographers & filmmakers can seriously consider adding another feather to their bow at pro quality, and without the worry of a trip to court.

• Best camera drones

• Best drones for beginners

• Drone flying for beginners

• Drone rules: US, UK and beyond

• Best DJI drones

• Best cheap drones

• Best FPV drones

• Best underwater drones

• Best drone accessories

• Best indoor drones

• Best travel drones

With over 20 years of expertise as a tech journalist, Adam brings a wealth of knowledge across a vast number of product categories, including timelapse cameras, home security cameras, NVR cameras, photography books, webcams, 3D printers and 3D scanners, borescopes, radar detectors… and, above all, drones.

Adam is our resident expert on all aspects of camera drones and drone photography, from buying guides on the best choices for aerial photographers of all ability levels to the latest rules and regulations on piloting drones.

He is the author of a number of books including The Complete Guide to Drones, The Smart Smart Home Handbook, 101 Tips for DSLR Video and The Drone Pilot's Handbook.