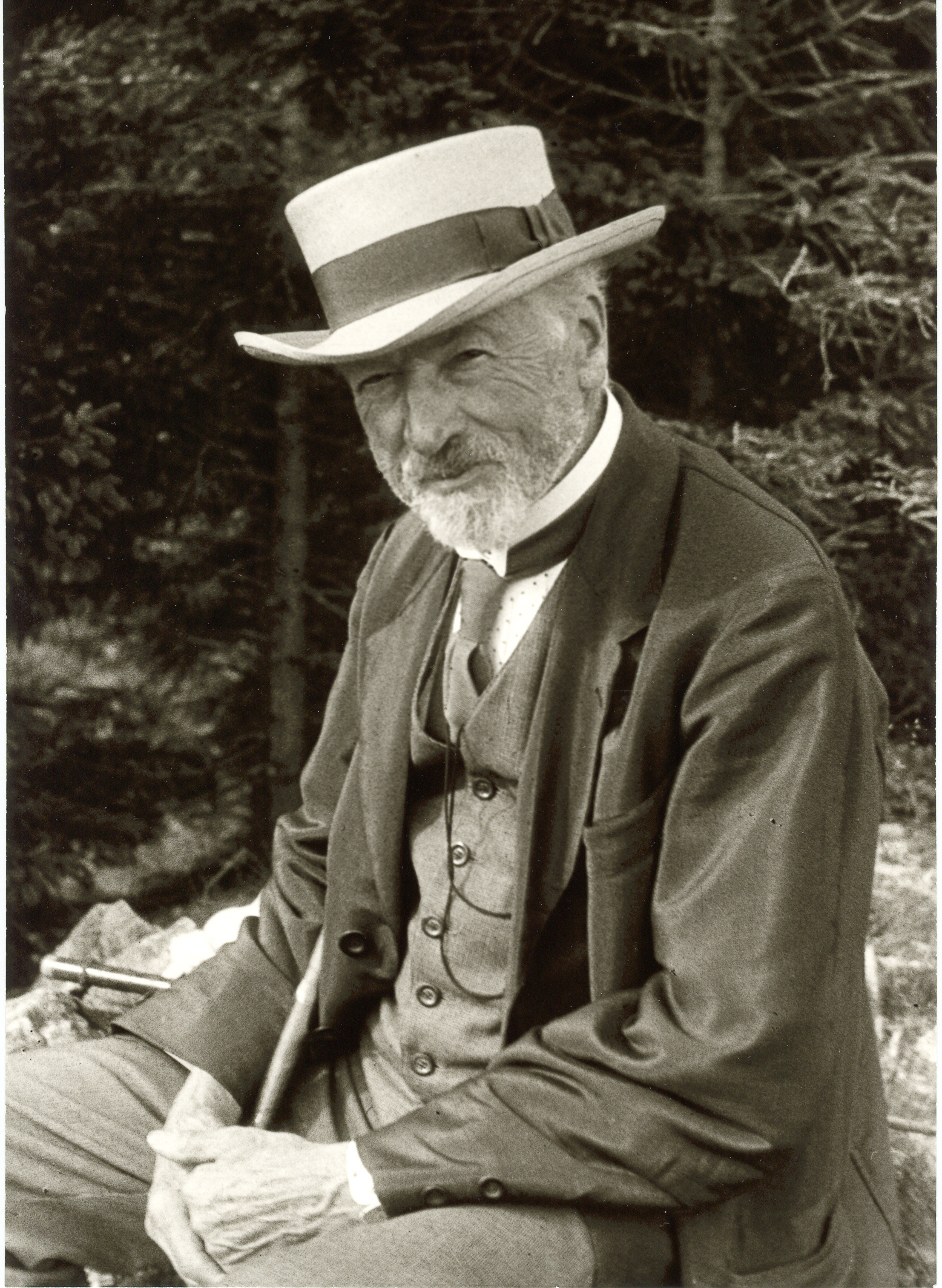

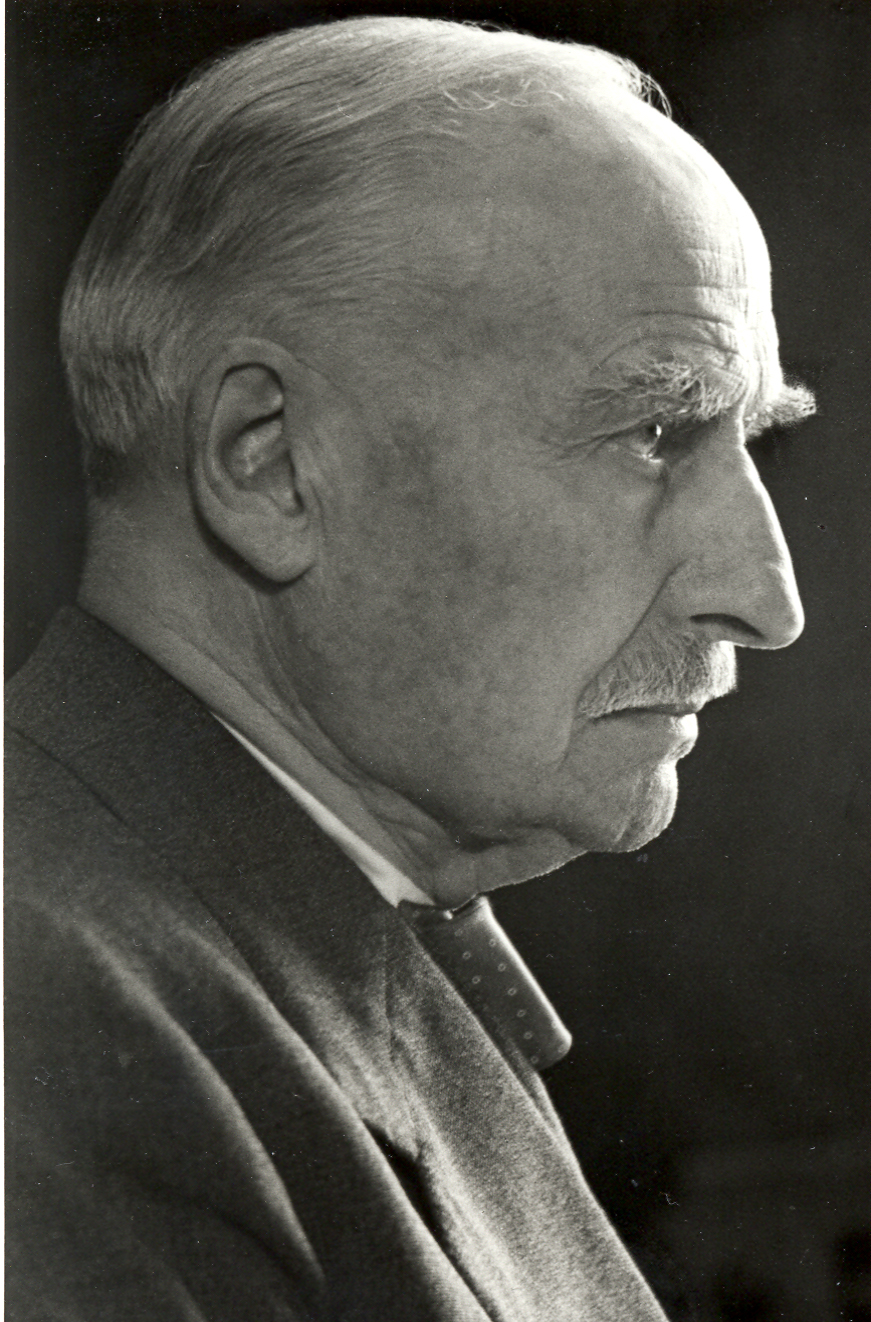

The name behind Leica cameras: Ernst Leitz II

The life of man behind Leica, and the importance of his father in the history of the company

In 1849, a mechanic and amateur mathematician, Carl Kellner, established a small optical company in the central-west German town of Wetzlar. The Optisches Institut made, firstly, telescopes and, later, microscopes. Known as the City of Optics, Wetzlar is in the German state of Hesse, about an hour’s drive north of Frankfurt. Kellner died of tuberculosis in 1855, aged just 29, and the business – which then numbered 12 employees – was taken over by his wife.

This article originally appeared in Australian Camera magazine, one of Digital Camera World's sister titles Down Under. Click here to find out more about Australian Camera magazine, including how you can subscribe to the print issues or buy digital editions.

In 1864, the company hired a talented optical engineer called Ernst Leitz, who quickly impressed enough to be made a partner in October 1865. Four years later, in 1869, he took over the whole operation – which was struggling to survive – and it was subsequently renamed Ernst Leitz Optische Werke. Leitz was just 27 at the time, and his entrepreneurial prowess saw the business expand rapidly during the latter years of the 1800s and into the start of the 20th century. By the turn of the century, Leitz was the world’s largest manufacturer of microscopes.

• Read more: Best Leica cameras

Ernst Leitz was also an innovator and devised a number of key advances in microscope design, including carbon arc lamps for better illumination of subjects, apochromatically corrected objectives for better definition of very fine details, and a bicentric reflecting condenser. In 1913, the company introduced the world’s first binocular microscope that revolutionized microscopy in scientific studies, laying the foundations for what is today Leica Microsystems – now a separate company from Leica Camera.

Ernst Leitz was 70 when the binocular microscope was launched, and he was helped in its development by his second son, Ernst Leitz II who, a decade or so later, would take on the challenge of launching the company into a whole new business – cameras – in the middle of a depression. Ernst Leitz died on 10 July 1920, aged 77, leaving the company in the hands of his son.

Commercial courage

Ernst Leitz II was born on 1 March 1871 in Wetzlar, educated at a Christian Lutheran school, and trained in both precision engineering and business management. He joined the family company in 1906.

Leitz Jr inherited a number of his father’s traits, including a keen sense of morality – no doubt founded in his staunch Christian faith – and the social responsibilities of being an employer. Back in 1900, Leitz Sr had introduced an eight-hour working day and a medical insurance scheme for his employees, both very progressive schemes for the time. Leitz Jr also had his father’s commercial courage and is famous for the statement which would, within a short time, revolutionise the way photographs were taken – “My decision is final; we’ll take the risk”.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

And it was quite a risk. The German economy was reeling from the effects of hyperinflation and extreme unemployment, and Leitz would be a newcomer in a market dominated by Zeiss and Kodak. What’s more, the plan was for a completely new type of camera never seen before. It’s perhaps not so surprising that most of Leitz’s senior managers were against the idea, forcing him not to make a risky-looking ‘executive decision’.

However, Leitz’s secret weapon was a compact and lightweight Kleinfilmkamera – a small format camera – which had been developed just prior to the First World War by one of the company’s talented optical engineers, Oskar Barnack. The basic design was refined a number of times prior to being put into production in 1924, but the big innovation was to use a film created from two 18x24mm cine frames to give an image area of 24x36mm, and so reduce the amount of enlargement required to make high-quality prints.

The early work on the camera was overseen by Ernst Leitz Sr, but he died in 1920 when the project still only consisted of prototypes. Ernst Leitz II assumed control of the company and began to take more of an interest in Barnack’s camera, primarily because he believed diversification was the key to survival in Germany’s challenging economic climate, and he was concerned about the future of his workforce.

“This small camera is an opportunity to create work for our employees – if it lives up to the promise I see in it – through the years of the Depression and to get them through the difficult times ahead.”

The camera was finally launched in 1925 at the Leipzig Spring Fair and called the Leica, the name derived from ’Leitz camera’. The Leitz name continued to appear on Leica cameras up until 1986, when it was decided to concentrate all the company’s photographic activities under the Leica brand. The familiar red dot logo appeared in the mid-1970s and was worded either “Leitz” or “Leitz Wetzlar” up to 1986.

Bigger risks: the Leica Freedom Train

After Adolf Hitler was named Chancellor of Germany in 1933 and the persecution of Jews began, Ernst Leitz II’s social conscience really came to the fore and he began taking risks that could have had fatal consequences.

Realising that much worse might lie ahead under the Nazi dictatorship, he began systematically but secretly assigning many of his Jewish employees to fake positions or training courses at Leitz sales offices overseas, giving them a legitimate excuse to leave the country. In fact, it wasn’t just his employees and their families, but also camera retailers and even friends of family members who were sent to Leitz’s sales offices in France, Britain, Hong Kong and the USA.

These refugees were even paid a stipend until they could find work, with Leitz executives scouring the wider photography industry, particularly in the USA, to secure them legitimate positions. They also each got a new Leica IIIB camera to take with them from Germany.

Leitz’s pre-WWII activities subsequently became known as “The Leica Freedom Train” and saved perhaps as many as 100 lives. His daughter, Elsie, was also involved in helping Jews leave Germany and was arrested by the Gestapo while assisting refugee women across the Swiss border. She subsequently spent three months in prison in Frankfurt. In the 1940s, the Nazis imported slave labour from eastern Europe to work in German factories, replacing military conscripts, and Elsie worked hard to improve the lot of those assigned to Leitz, again risking imprisonment.

Typically altruistic, Ernst Leitz II kept it all secret even after the war and forbade others, including his son Günther, from ever telling the stories. It only all came to light in the mid-2000s, earning him a posthumous Courage To Care award from the Anti-Defamation League in 2007. According to his grandson, Knut Kühn-Leitz (son of Elsie), the family credo was always “do good, but do not speak about it”.

The later years

After the 1925 launch, Leitz’s resolve would have undoubtedly been tested again because, although revolutionary, the new Leica camera attracted mixed reactions and sales were initially slow. Fortunately, he had shrewdly kept the initial production run very small (less than 1,000 units), so when demand began to grow, it quickly outstripped supply, which is always a clever marketing ploy. By 1936, though, a total of 200,000 Leicas had been built, proving the emphasis on optical and mechanical precision in a more compact, portable package had been right.

Ernst Leitz II successfully steered his company through the most challenging of times, but never lost the personal touch with his employees, including a daily tour of the factory. He reportedly made a point of learning all his employees’ names and never forgetting them. He was described as having “an instinct for development potentialities” and “great organising optimism”.

By the end of the Second World War, Leitz was in his mid-70s and had suffered a stroke (probably due to stress), but was still actively involved in the running of the company. The original Leica had evolved into a much more sophisticated camera with a diecast bodyshell, interchangeable lenses, a coupled rangefinder and a top shutter speed of 1/1,000 second.

In 1946, production of Leica cameras reached 400,000 units, but in the immediate post-war years, there were problems with the supply of raw materials and the ongoing threat of a Soviet invasion. Ernst Leitz II elected to move some production to a facility in France and, later, in the early 1950s, an operation was established in Canada – seen as a safe haven in the likelihood of another war.

In 1949, Ernst Leitz II was made an honorary citizen of Wetzlar and in the same year the company established a research laboratory to work on the formulations of optical glass in the pursuit of ever-better lens performance. Along with his second wife, Hedwig, he built a magnificent new home – Haus Friedwart – above and behind the original Leitz factory in the middle of the city, now home to Leica Microsystems.

It remains a clearly visible landmark from Wetzlar’s historic old town area. Leitz’s first wife, and the mother of three of his children, died in 1910. One of his sons, Ludwig, was the driving force behind the next most important milestone in Leica history, the Leica M3.

Launched in 1954, development of the M3 had begun just after the Second World War and Ludwig, along with chief engineer Wilhelm ‘Willi’ Stein, designed (and patented) one of its key features – an integrated and combined viewfinder and coupled rangefinder which also incorporated the projection of image area frames for different lens focal lengths with automatic parallax correction.

Ernst Leitz II was alive to witness the birth of the M3, but now in his early 80s and increasingly frail, he had handed control of the family business over to his three sons… Ernst Leitz III, Ludwig and Günther (who was born to Hedwig in 1914).

Ernst Leitz II died on 15 June 1956, aged 85; a very important place in the history of camera design – and photography more widely – undoubtedly assured.

Read more:

Nikon, Leica & Hasselblad: the cameras that have been to space

Leica's lens naming explained

Best Leica cameras

Leica SL2-S review

Best Leica SL lenses

Leica Q2 Monochrom review

Leica M10-R review

Australian Camera is the bi-monthly magazine for creative photographers, whatever their format or medium. Published since the 1970s, it's informative and entertaining content is compiled by experts in the field of digital and film photography ensuring its readers are kept up to speed with all the latest on the rapidly changing film/digital products, news and technologies. Whether its digital or film or digital and film Australian Camera magazine's primary focus is to help its readers choose and use the tools they need to create memorable images, and to enhance the skills that will make them better photographers. The magazine is edited by Paul Burrows, who has worked on the magazine since 1982.