This photography project sat in the basement for 40 years – now it's a modern classic!

After sitting in a box in the basement for 40 years Lisa Barlow's 'Holy Land USA' gets its due recognition

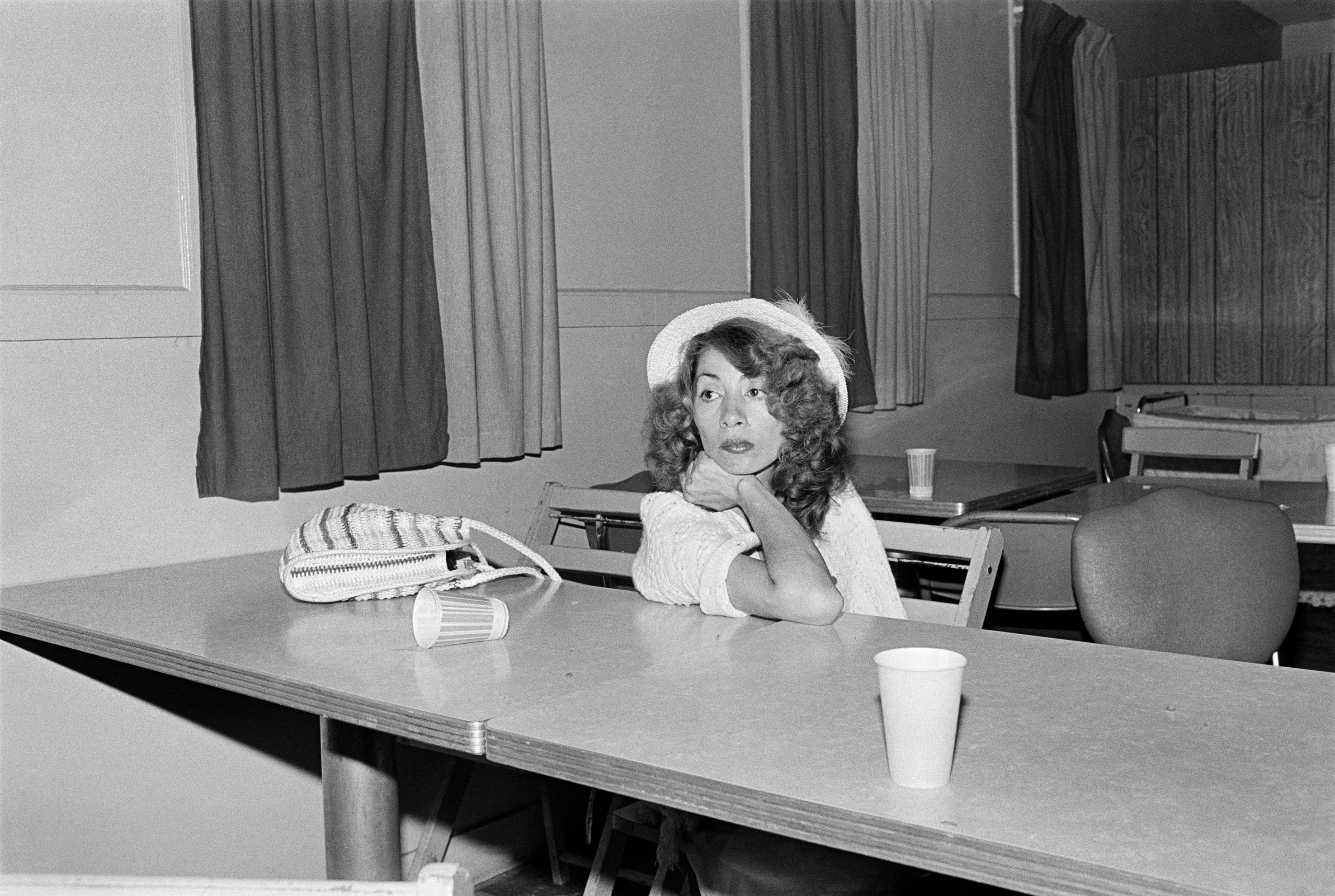

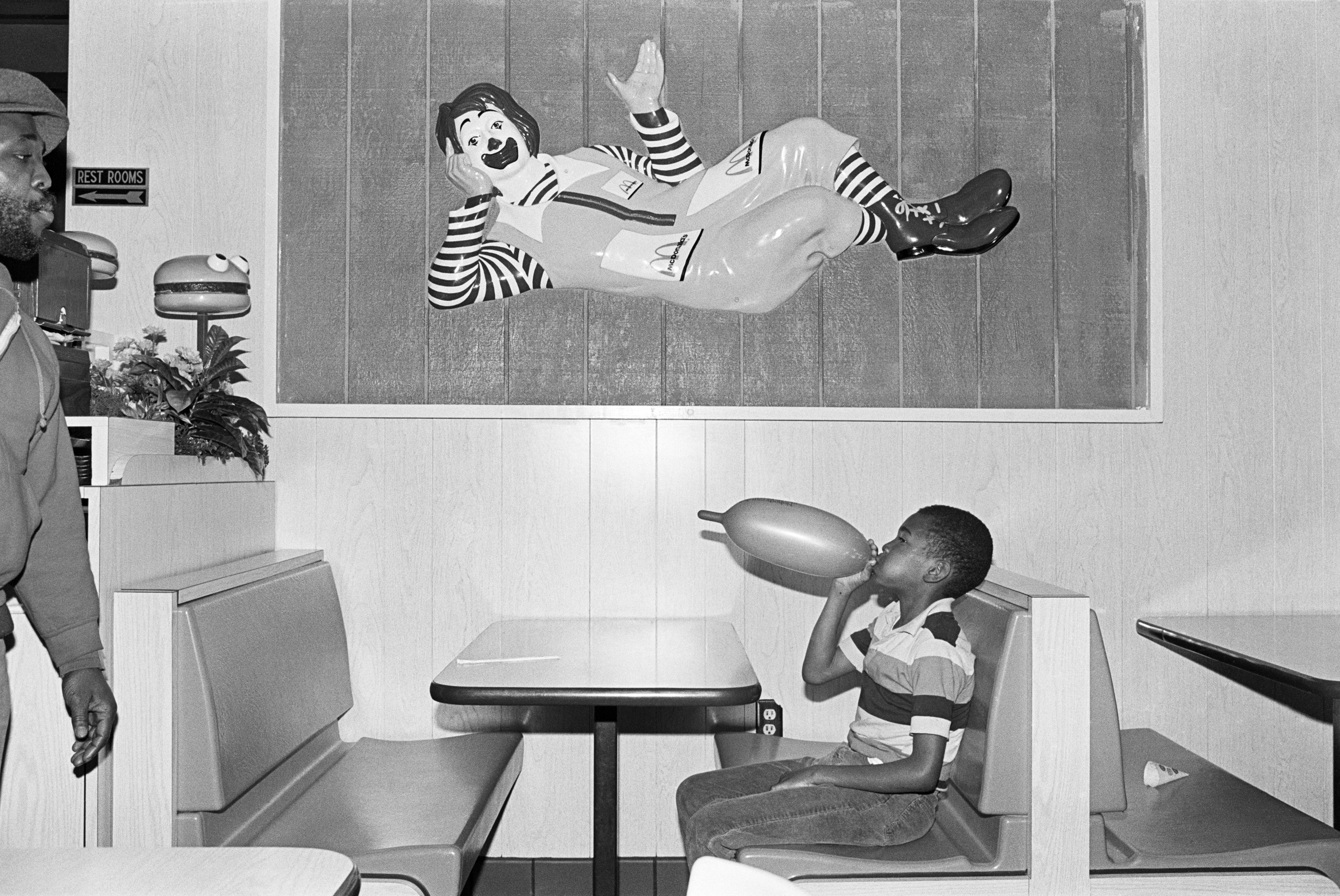

Before looking through Lisa Barlow's incredible new photography book, I had never heard of Holy Land USA or the nearby village of Waterbury – but, by the end, I felt I knew it and its people.

Shot in the early 1980s, Holy Land USA by Lisa Barlow had been patiently waiting in a box as a set of negatives in a New York basement for the last 40 years, only recently unearthed due to the pandemic.

With the assistance of esteemed photography book publisher Stanley / Barker, the collection of stunning black-and-white photographs was transformed into a new photography book. Now that the work has finally been shared, it is receiving the long-overdue recognition it deserves.

After stumbling across a manmade model representation of the Holy Land in Connecticut, Barlow needed to know more. What at first glance looked like a fun kitsch diorama, had a deeper meaning to the population of its neighboring town.

Holy Land USA is a documentation of the town, its customs and its people, from captivating street images to immersive private moments in local family homes. Recurring characters provide a strong narrative of life in this small town, creating a connection between viewer and subject.

It has been a while since I have seen photography transport me to a place like this, providing an insider's view of a different way of life, a community and, in this case, a different time. It reminded me of the photography of Chris Killip, not so much for the aesthetic, but for how he would embed himself into communities for his projects such as Skinningrove and Seacoal.

Eager to learn more about Lisa Barlow's background in photography, her experiences making this project, and her approach to capturing authenticity, I was fortunate enough to sit down and speak with her.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

How long have you been taking photographs and what first drew you to capturing the world through a lens?

It's funny, but I have these early memories of loving carrying a camera. My parents gave me a few – have you ever seen a Polaroid Swinger? It was this big white camera, you might have seen old vintage pictures of them, my parents gave me one when I was nine and a few packs of Polaroid film. I think that was probably my first camera.

Then I discovered my grandfather's old camera and then my mother had a camera, but when I was 13, I saved all my babysitting money and I bought a Pentax and that was my first real camera.

Did this love of carrying a camera carry on through your teenage years?

Yes, I was really lucky. I did a summer school session where I was supposed to learn French and then I got to pick a second thing and it was photography. I was exposed to good teachers and I remember I went to a Diane Arbus exhibit in Massachusetts and I just went, "This is amazing, this is what photography is!"

I continued through high school with good teachers and then through college and continued looking at work, learning from other people, and being given good assignments.

I think the best assignment was in a program called Visual Studies and we were sent out with these little plastic Holga cameras. We were asked to find faces and so all of a sudden you start looking around and my god, there's a face in that parking meter, there's a face in the reflections in that window, things that weren't faces became faces.

I think I really enjoyed learning to look that way and then learning to look through the viewfinder. Certainly a lesson in letting go of your presuppositions and allowing visual discoveries.

Did you take this in your approach to making future work? You certainly find this feeling of being present in Holy Land, USA.

I would say by then I was in college and I had taken a year off in Paris. I came back and I was a little bit out of step with my classmates. They moved on, so I took another photography class which happened to be with Tod Papageorge. That year I took a class with Larry Fink and one with Tod Papageorge. I mean those were iconic photographers who were also excellent teachers.

He was able to correlate a Keats poem with photography and taught me that you're allowed to use your brain. You're allowed to feel things when you are taking pictures, and that's really when I began to make my best work.

This particular work was created because I didn't have many friends to hang out with at school so I was able to go off on the weekends. It started out as doing my homework but it really became a passion for meeting these people. They became sort of family members to me in a way. You wouldn't know that at first glance but I really went in deep with some of these families.

I wonder if you could briefly describe what Holy Land USA is and your first encounter with it?

My first encounter was, I heard about it but then had forgotten about it, until one day I was driving and I saw this huge cross looming over the city on a hill and I was curious. I had my camera, went over and I was startled by this little diorama of the Holy Land, sort of like Disney World. Italian immigrants used some of the skills from Italy to use plaster and concrete in these recreations of the cross and illustrations from the Bible.

It was the kitschiest thing I had ever seen and I just wanted to document that. It was initially funny to me, but then I started meeting the people who were going there for whom it meant a great deal. I met the man who built it, and I met one of the nuns that lived there. It wasn't a trailer convent, but it was sort of like that, and I realized that this was deeply meaningful to them. This made me take it more seriously and respectfully.

I went down to meet some of the people in the town and that's when I first started meeting kids on the street who then invited me home. From there, I began to make real friends and connections and I kept going back for several reasons.

The holy part starts as this religious shrine that is very important to this predominantly Catholic city, but the holiness has sort of a lowercase H by the end of the book. I just wanted to capture these people who were going about their lives and sharing them so generously with me – that felt kind of holy to me.

How long did you spend shooting this project?

A year and a bit, but pretty much the school year 1980 to 1981. It was about a 30-minute drive from school and I would go on Sundays or Saturdays. Some Sundays I'd spend the night there.

It's extraordinary if you think about it. I was a 20-year-old, my parents were divorcing, and I was away from home and alone, then suddenly this incredibly warm embracing family was so generous with me. I loved being part of that family, and I loved it when they invited me to stay with them.

When was this work created?

I shot the work in 1980, a long time ago, but I didn't know that I had something wonderful at the time.

I think I entered it into a prize or something at college and tried taking it to a few publishers but the time wasn't right. I think the phrase I got was – "There's no market now for concerned photography".

I was a little bit bummed out but then life goes on and you've got to find a job. I started working, I moved to New York, and kept taking pictures here. Then life goes on a little bit further and the negatives are just sat in a box in the basement.

Then the pandemic hit, and I thought I should learn how to scan negatives. I took out this project and then I began to look seriously at it and scan it. I learned how to scan it better and then shared it around.

So it had two iterations: the making and the discovery. I'm just so grateful that it's here again, and that I can share it!

How much of the shooting process was instinctual, and how much did you plan?

Let me put myself back. I would have been looking at a lot of amazing work, Robert Frank's The Americans and a lot of Gary Winogrand's work. I also learned from Larry Fink the year before, so all of that was in my head. I wasn't trying to copy them but I was certainly informed by them.

I had this feeling when shooting where you're just in the moment and it's exactly where you need to be. You stop thinking and just start reacting, you're just in some place where time doesn't exist. Everything is just where you are in that minute, that moment.

I think that's where this first happened to me and at the time you sort of can't believe it, you can't control it, but at the same time, you are willing for certain things to happen.

You mentioned some inspirations of yours and it feels like you're pulling from several sources. To me, the way that you embed yourself within these families reminds me a lot of Chris Killip's work. You just seem to seamlessly blend in and they almost don't know you're there. I wonder if you could speak about that approach?

I love Chris Killip's work. I think it's because I loved being with them. It almost felt like I was just living. This was just part of the life I was living too, so it wasn't like an assignment. I went on to have assignments to document certain things, but here I felt like I was just part of the picture, maybe an ingredient that Chris would have probably felt too.

They were happy to have me there, but I think it was also a different time. I don't know if it's as easy now. There are extraordinary photographers doing it still, but it does take building up of trust and the familiarity of being there so much that you do become, not the wallpaper but easy to ignore.

What made you decide this is the right time to share the work?

Okay, it's pretty specific. I was talking with a friend about Vivian Maier's work and I thought, my God, what if nobody ever sees this [Holy Land USA] – I don't want that. I want to enjoy sharing this.

If no one had bought those pictures from the storage locker and they had gone into the dumpster we wouldn't have that work. I mean I'm not equating myself with her, god forbid, but It was a lesson in doing the work it took to bring this out and share it. It was fear of the work being lost.

Has this project impacted or informed your current practice?

Yes! I've never stopped taking pictures and certainly, for years I was just using my photography a lot on the subway and in art museums trying to create little narratives not of people I know but of strangers.

But I'm beginning to think that I would like to create a situation where I do know the people and I'd like to enter into that kind of relationship again. I mean, I do it with my family all the time, but it's made me want to see if I can explore a different community in a similar way.

Can you remember what equipment you used for this project?

By then I had bought a used Leica M6 and I had one lens, which was a used 35mm, and that was it. I knew I had to use a Leica because Gary Winogrand used a Leica, and many of the graduate class above me were starting to use Leicas.

I was paying attention to what other photographers were using, so once again, I'm not sure it was babysitting money this time, but I saved for another camera.

The Leica look is very distinctive and a favorite among documentary photographers, photojournalists and street photographers. I think the rangefinder enables the photographer to remain more present at the moment and more aware of their surroundings.

Yes, it's just so small too. I saw Cartier-Breeson on the street once and it was incredible. His camera was all covered in black tape so that you wouldn't notice it and it was almost like it was attached to his hand, lurking for his decisive moment.

I use a Fujifilm GFX now, which is a big bulky thing. I love it, but, I did just this morning see the advert for the new Leica Q3 43 and I thought maybe it's time to go back to Leica!

The book, Holy Land USA, includes a fantastic essay by photography writer Brad Zeller. How did that collaboration come about?

I have been in a program with the Penumbra Foundation, which has a photography book program, and I was making work out of a project I am periodically working on in Texas now. Brad was one of the visiting lecturers that came to speak and I met with him on Zoom.

I also did the Chico Review, where photographers go and meet other photographers and have their work looked at, and Brad was there. He saw the work there, so when I approached him for this project he was gracious enough to be enthusiastic and say yes. I am tremendously grateful because I love his writing, even his Instagram captions are electric and charged.

Barlow's book is a modern photography classic with a timeless soul. It captures a world long gone and provides a window into a very specific place at a very specific time, as if unearthing a time capsule that we are now allowed to peer into. I for one am very glad was rediscovered and shared!

Holy Land USA by Lisa Barlow is published by Stanley / Barker and is available now.

Stanley / Barker has been publishing some incredible photography books recently, including Robbie Lawrence's Long Walk Home and Trent Parke's Monument. These and more will be on display this weekend at BOP (Books on Photography) at the Martin Parr Foundation in Bristol, UK.

Check out our guides to the best coffee table books and the best books on street photography.

Kalum is a professional photographer with over a decade of experience, also working as a photo editor and photography writer. Specializing in photography and art books, Kalum has a keen interest in the stories behind the images and often interviews contemporary photographers to gain insights into their practices. With a deep passion for both contemporary and classic photography, Kalum brings this love of the medium to all aspects of his work.