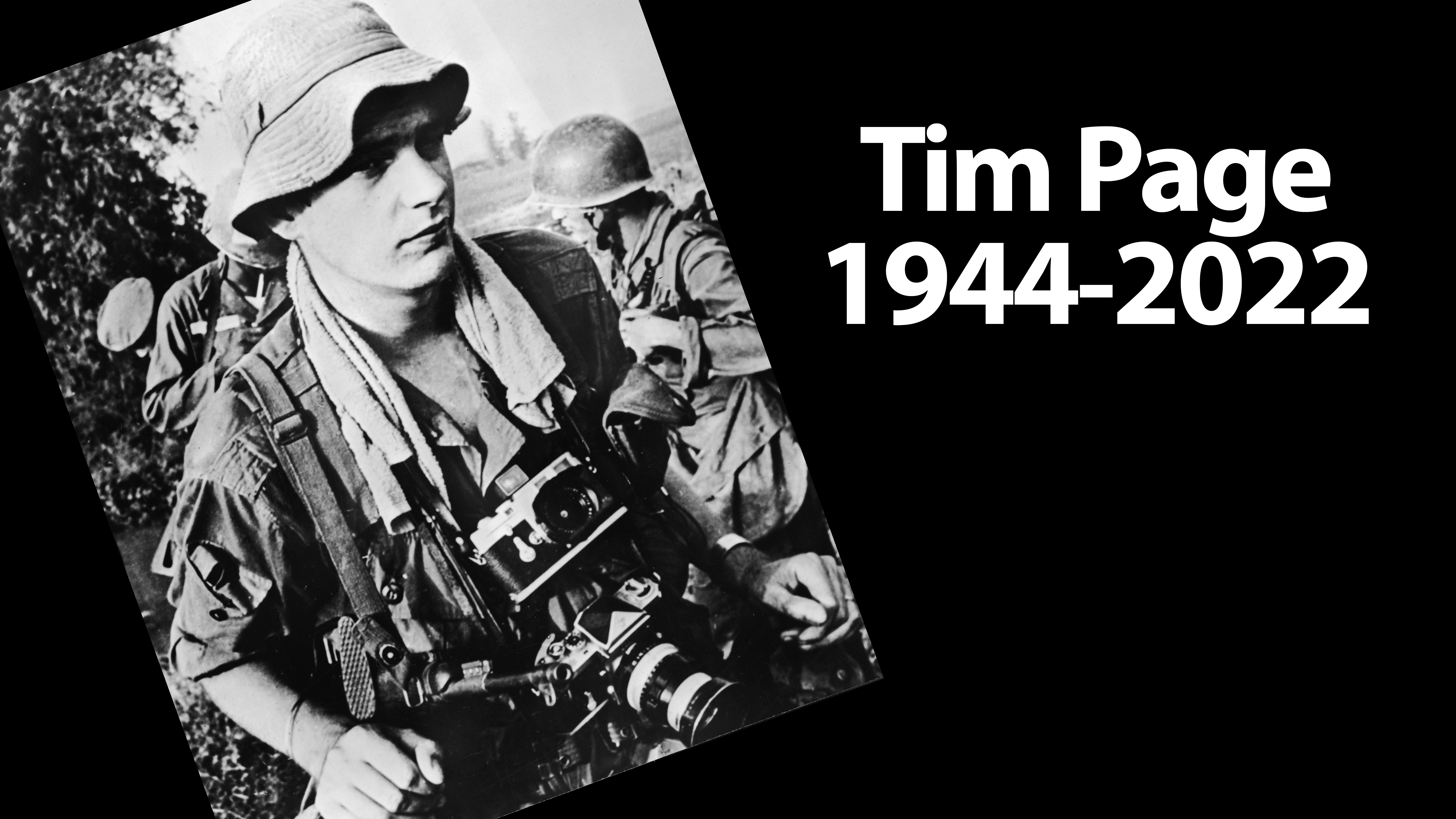

Tim Page 1944-2022: legendary Vietnam war photographer dies aged 78

Legendary war photographer Tim Page has died at the age of 78. He was best known for his work chronicling the Vietnam War. His gonzo lifestyle was the inspiration behind the photographer character in the film Apocalypse Now, played by Dennis Hopper.

Born in the UK in 1944, Tim Page left England aged 17 to travel the world with his camera, and got his big photographic break covering the Laos civil war in the early 1960s.

In 1965 he moved to Saigon and spent the next five years covering the Vietnam war. His work was used by Time-Life, Paris Match and the Associated Press.

Page wrote nine books, including Tim Page’s Nam and The Mindful Moment. Page also founded the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation to honor all the journalists killed in the region.

He settled in Brisbane, Australia, where he was an adjunct professor of photography at Brisbane University.

He died on 24 August 2022 of live cancer at his home in Fernmount, New South Wales.

Tim Page interview from 2015

Keith Wilson spoke to Tim Page back in 2015, just after the 40th anniversary of the Vietnam War. This interview was originally published in N-Photo magazine.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Legend is an over-used word, but not in the case of Tim Page. While covering the war in Vietnam, he was wounded in action four times before he was 25. His life has been immortalized in books and on film, including Michael Herr’s seminal work Dispatches and the Academy Award-winning epic Apocalypse Now. Today, he lives in Brisbane, where he works as a professor of photojournalism in Australia, but Vietnam remains the one story everyone still wants to hear about…

You’ve just come back from the 40th anniversary celebrations of the end of the wars in Vietnam and Cambodia. What was the overriding emotion?

There’s a place called the War Remnants Museum in Saigon, now called Ho Chi Minh City. That is the only place in the world where Requiem, the pictures from the book honoring all of the dead and missing photographers, is on permanent display. I was doing seven interviews a day and I got pinned in front of the main wall, and for some reason I just became unwound and burst into tears. I think that was the only emotion I went through. The emotion of going back and being with a bunch of old mates is always good, and I’ve been going back every year since 1985.

Many of your colleagues didn’t survive and you were nearly killed, so why did you keep going back?

I think there were two reasons. One, because the story was bigger than we were, bigger than anything. Okay, there were other conflicts during the ten or 12 years of the Vietnam War, especially in the Middle East, but in terms of this story if you were a journalist in the ’60s and you didn’t go to Vietnam it was like not earning your stripes. I went back in 1968 because every time I opened the paper or turned the television on during the Tet Offensive, all I saw were my mates’ pictures or my mates’ footage, or my mates’ stories. It’s galling sitting not doing very much on the West Coast. So I sold my car and got a one-way ticket back.

It wasn’t just about the story. IndoChina is a romantic, marvelous place that you can’t really explain, except in the Graham Greene kind of sense. It has its own allure. I’m not just talking about the colonial times, I’m not just talking Vietnam. I’m also talking about Cambodia and Laos. It’s almost like a bad piece of junkie drug in a sense: once you’ve been there and it’s held you in its grasp for a bit, you get immersed in the culture. If you’re going to have a war, at least have a war in a place where the food is good and the women are beautiful.

You had no intention of working as a photographer, so who introduced you to photography?

My Dad. I got an Ensign, like a British-made Box Brownie, on my seventh birthday. My Dad processed the film in the bathroom. When I was 11, I bought a camera when I was in Holland, changed that when I was 14, bought another camera in Germany, which went all the way overland to Madras in the Combi van. I sold it in Kathmandu and bought another camera in Burma on the way to Thailand, which I used to shoot incredible pictures of Burmese rebels and all kinds of stuff. That was nicked in a brothel in Bangkok.

The next camera I bought I was in Laos, in 1964, and I used it to shoot the first pictures I ever sold to UPI [United Press International]. Then, literally months later, I bought a Pentax with money from stringing fees from UPI, and with that camera I shot the pictures that got me the job in Vietnam. The rest is history.

When did you get your first Nikon?

My mate, who was UPI staff correspondent in Laos, was shooting with a Nikon he bought in Tokyo.

I borrowed his camera and I had my Pentax to shoot the attempted coup in Laos in ’64. As soon as I got to Saigon the bureau chief lent me one of his spare cameras. So just before the American marines landed on March 8 1965, I had my first Nikon.

A Nikon F?

A Nikon F, which came from Tokyo. They were $90 a body, silver. They were so cheap. If you went to Tokyo at that time you could go to the factory and watch your Nikon coming down the line.

Was it only Nikon gear that UPI was using?

The only gear that people used were the Leica M and Nikon F. I knew one person at AP who had a Canon and one who was left-handed and had an Alpa! I started with a Pentax, which lasted six weeks. It didn’t like the dust, the humidity. I’ve still got it. You can’t wind it on, you can hardly take the lens off, the back only opens with a screwdriver. It wasn’t designed to work in a war zone.

When you were going into the field, what would be in your bag?

The best version of the camera bag was the US military medic’s bag, which folded up into a flat roll pack. It opened up to have three or four pockets which had all that plasma and stuff in. Eddie Adams had them copied in leather.

By the time I got fired by UPI I would freelance for Paris Match for a month and then freelance for Life. For Life, if you shot black and white you got $300 a page, but if you shot color you got $600 a page. It doesn’t take much to figure out what you’re going to do – you’ve got to have two cameras! Often one would be a Nikonos because of the rainy season and dust, a Leica and then a Nikon F over your shoulder with a 105mm. I had the tub [case] which the 200mm f/4 came in gaffer-taped onto my webbing so I didn’t have anything bumping onto my hip.

What else would you take?

Water. You’d have four to six canteens, as well as a bladder on your rucksack. You couldn’t carry enough water if you were going out for more than three days, four days, five days, but you didn’t know how long you’d be gone.

Imagine you had a digital camera covering the Vietnam War. How different would it have been?

This subject came up quite a lot on this last visit. I doubt very much if digital cameras would have survived! Don’t get me wrong, some are tough as nails. I’ve put them into concrete, I’ve put them into water, I’ve done seriously bad impact things to them, but in Vietnam in the monsoon season I don’t think a digital camera would have kept going. Autofocus does not like wet weather. So you want manual. I didn’t have a camera with a light meter until I got my first Nikon FM.

I never had a light meter!

You worked in color and black and white. Were you thinking ‘This is a color shot’, or ‘This will look better in black and white’?

It was more mercenary than that. I realized my black-and-white film could be turned round faster in Saigon. When I was shooting for Time, Time would want pictures on a Tuesday, for going to press on the Wednesday. Life wanted the pictures on a Wednesday for going to press in Chicago on a Thursday or whatever. If I processed the black-and-white film as soon as I came back in from the field, then I could wire the pictures to them via AP or via UPI. Also, it gave me the advantage of writing fuller captions because I could see the pictures. You kept caption notes as much as you could, but the rest of the time you only took rough notes of what was going on.

You didn’t have the technology we have today…

There were no mobile phones, the telex wasn’t very quick, planes still had propellers! To get from Saigon to London it took 27 hours. There was no non-stop flight.

Would the people who are shooting wars now have survived in Vietnam, never mind their cameras? They’re dashing in and out of conflict like yo-yos. I’m not decrying their work, but a war is something they visit. Most of the people who covered Vietnam lived there. People like Don McCullin came in for six weeks or two months, same with Philip Jones Griffiths. Okay, Larry Burrows lived in Hong Kong, but he was in Vietnam almost constantly.

As you say, Vietnam also had an allure, even in war...

Vietnam was a very nice place to live. If you were a 20-year-old kid, there’s all these beautiful women, the food’s good, you’ve got a helicopter taking you to wherever the action’s going to be, you can ride in a fighter jet, you can basically almost run your own private war. And the Americans were falling over themselves, ironically, to get the war publicized. They thought they would look good if, when they got ambushed, it came out as six pages in Life! They didn’t realize that a strong war picture would come out as a strong anti-war picture. Even when knocking on heaven’s door, they’d almost be wanting their image made. Guys with sucking chest wounds would say, “Take my picture so my Mum can see it”.

Which is the more accurate portrayal of you in a film Iain Glen in Frankie’s House (based on your autobiography) or the anonymous photojournalist played by Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now?

I’ve never watched Frankie’s House from end to end. I was getting daily rushes as it was being shot. I have never seen such bad camera. They didn’t need to rewrite history: real life was just as good as the invented one. I found it so appalling, and yet I worked with Iain Glen before he went off to shoot. He was wearing my fatigues, he was wearing my hat, I tried to coach him as much as possible, and I tried to get the script to come back to a bit more of a reality check. Impossible.

With Apocalypse Now, whatever Dennis Hopper is playing, he’s playing Dennis Hopper. I think Coppola has made an incredible anti-war film by using the totally surreal. In a sense Apocalypse does achieve those very surreal moments that war is, and at the same time makes a very good anti-war statement. Any good war picture becomes an anti-war picture, hopefully.

Was there any censorship?

In a sense the only censorship we faced was that we wouldn’t release pictures of the dead or the dying until the next of kin had been notified. It wasn’t so much censorship as a humanitarian consideration.

Do you think photography now has the same impact on public opinion as it did during the Vietnam War?

No. Nowhere near. Because of the internet, daily I am saturated with a tsunami of images. Some edited, and some nicely presented, but most of it is just a tsunami of mundanity. It’s all right to say it’s easy to shoot a picture, but how many people can edit a picture? If you’ve got a roll of film of the most god-awful firefight in Vietnam, can you go through that roll in two minutes and get the right picture moved on the wire? We don’t have photo editors any more. We have image managers! What does that mean? Most of them are a bunch of people who have never picked up a camera in their lives and there are so many images they don’t know where to start looking.

Where do I go for the top pictures? There are so many alternatives now. There’s so much that it’s very hard to find a very nice, tightly-edited 10-page spread. I’m saturated with stuff that I have no desire to see, but I have to wade through it to get to the core. Last year, 138 newspapers folded in America alone. We no longer have the magazines that lie around on a coffee table. Everything now is a delete button.

Your mentors included Eddie Adams and Larry Burrows. What did you learn from them?

I don’t know quite what you actually learn from a peer. I think a lot of what happens photographically is a very osmotic process. You hang on with somebody and you go into the field and you’re in the same fight, the same humid heat and dust, and in a sense it’s like watching somebody who teaches you. You watch how they move, you watch how they reload a Nikon F, where you’ve got to take the back off during combat – how do you protect the inside back of a Nikon in the middle of a firefight? Do you make that decision on the 33rd frame? Do you take the film out? If the shit hits the fan you’re going to need more than two frames. If the shit’s hitting the fan, you don’t want to be reloading the thing. That famous picture of Nick Ut’s of the burning girl, the complete frame has got David Burnett running alongside rewinding his M3!

Is there a picture that you think is most representative of the war?

You could pick out a lot of individual pictures. I think it was that constant barrage of incredibly high ground pictures that were iconic, which were basically daily. Then every week Life or Look, or one of the major magazines, would run a big spread. And the Japanese: we tend to forget because of the big names like Larry and Don, that there were equally as big stars in Japan. Kyoichi Sawada was a Pulitzer Prize winner, murdered in Cambodia.

There were great French photographers too in Vietnam: Marc Riboud came and went back in 1972. A lot of guys didn’t make it. The last guy who died in the war, on the last day of the war, was a French photographer, Michel Laurent. They produced an incredible body of work. And then we completely forget the Vietnamese photographers, the people on the other side.

You took a lot of drugs in Vietnam. Did they help or hinder your work?

That’s a very good question. I don’t think they have ever hindered it. It should be stated that most of the time I never imbibed in the field. Maybe at the end of the day or after a really blitzy action, I’d have something rolled and smoke. But not during peak madness, as it were.

The ultimate response or challenge to a question of that nature is to say I defy somebody to go through my pictures and tell me which pictures were taken stoned or otherwise. I can’t tell the difference any more. I’m going back over my archives for a retrospective at the moment, and I can remember a lot

of the circumstances surrounding the making of the image. Most of

the time I was probably stoned.

Does your celebrity – dare I say notoriety? – ever embarrass or irritate you?

It got a bit boring in Saigon this last trip. I was doing seven or eight interviews a day. In a certain sense, yes, because as Cartier-Bresson says, “We’re supposed to be invisible”. I suppose the notoriety has opened doors in some ways, too. It’s a two-way street. I’d prefer not to be known in terms of being bothered while I’m trying to shoot people on the march on the 40th anniversary, but on the other hand, as Larry gave me the time of day back then, you’ve got to do the same for people now.

If it gets you in the door and it gets you an assignment I think that’s great. I get calls out of the blue for jobs I’d never even think about before: doing stage plays, doing dance, doing theater. I got a call from The Clash: “Can you do an album cover for us?” I’d never even heard of The Clash! I had a marvelous time with The Clash, I was on the road with them for three weeks and they were using my pictures back-projected on stage for Combat Rock. It was a lot of fun and I wouldn’t have done that if it hadn’t been for the notoriety.

It’s been an eventful life – is there anything you’d do differently?

I wish I’d shot more film. Now, I realize not how little I shot, but it would have been good if I’d shot more. We were too busy just staying alive. I did a big cull in the ’70s of my stuff from Vietnam and I wish sometimes that I hadn’t. I threw away stuff that now might be in the Tate Modern. But you can’t use the word ‘if’. The last line in my autobiography is: “There are no ifs and buts. You only go around once”.

A former award-winning editor of Amateur Photographer magazine, Keith is the founder of Outdoor Photography, which he edited from 2000 to 2007, Black + White Photography and Wild Planet, the world’s first monthly digital magazine devoted entirely to wildlife photography. He is a highly regarded competition judge and since 2016 has chaired the jury of the Nature Photographer of the Year awards. He is the co-founder (with Britta Jaschinski) of Photographers Against Wildlife Crime™, an international group of award-winning photographers who have joined forces to use their powerful and iconic images to help bring an end to the illegal wildlife trade.

- Chris GeorgeContent Director