Last week the Digital Camera World was out in force at Adobe Max 2025, where the company behind Photoshop and Lightroom was keen to boast about its latest AI features.

These range from the reimagined Actions panel, which analyzes images and suggests edits, to Select Details, which automatically isolates hair and facial features.

But while they're presented as tools for photographers to enhance their workflow, I have a worrying feeling they might be replacing the art of photography altogether.

Of course, the line between enhancement and fabrication has always been blurry. Once it was dodging and burning in the darkroom, then it was layers and masks in Photoshop, now it's AI. So nothing really changed… right?

Well, I'm not so sure. Maybe I'm getting old, but the latest wave of AI-powered tools feels different. With just a few clicks or a simple text prompt, entire elements of an image can be replaced, recomposed or generated from scratch. And my question isn't whether we can do these things, but whether we should.

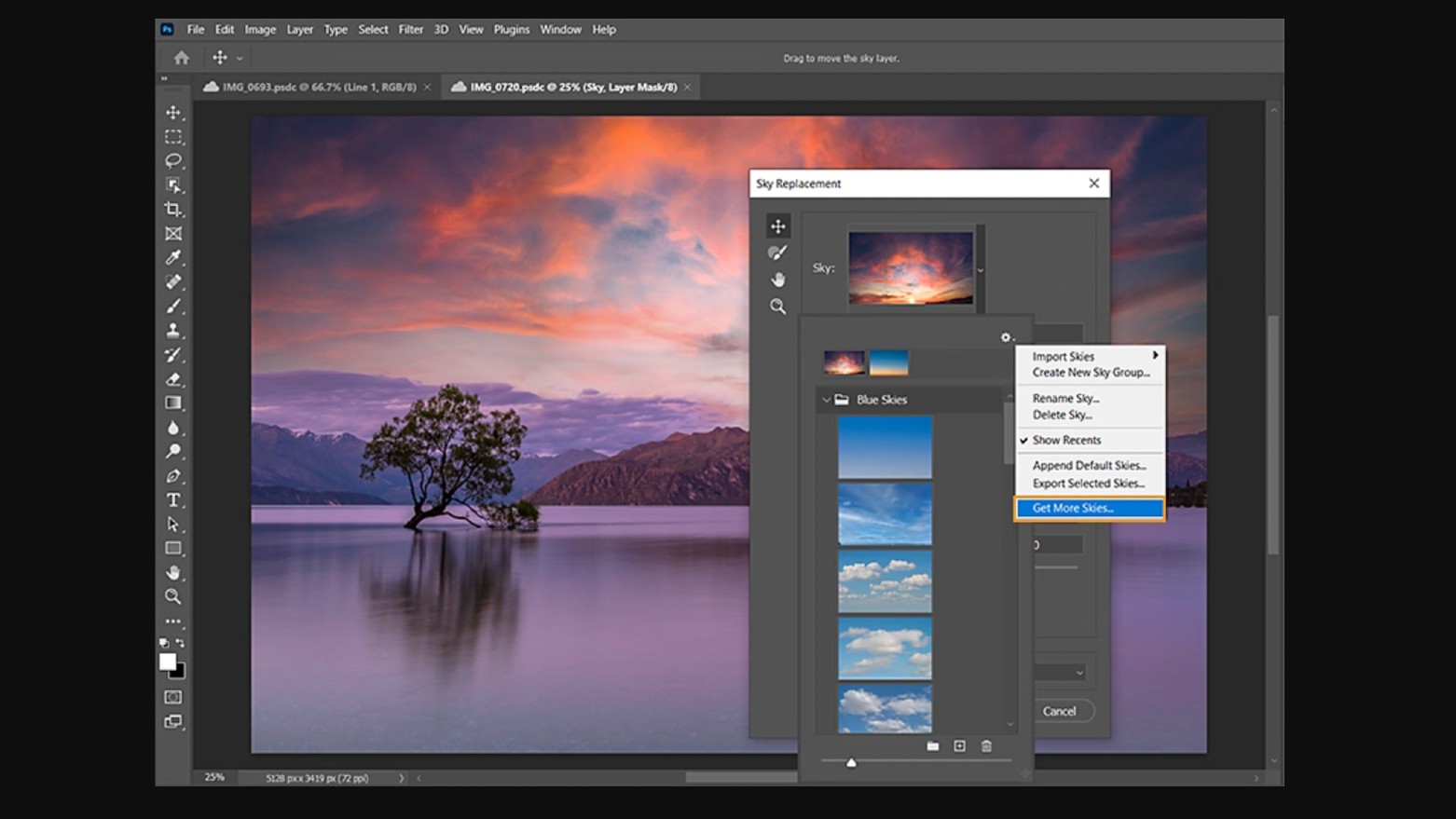

Take the new landscape masking tools in Lightroom, which automatically identify skies, water and foliage for one-click adjustments. Convenient? Absolutely. But when paired with the growing arsenal of generative capabilities, we're moving from adjusting what's in the frame to wholesale replacement of reality.

To put it another way, that azure blue sky with perfect cotton candy clouds wasn't what you saw that day; it's what an algorithm thinks would look better. And to my mind, that's a problem.

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The eclipse of personal perspectives

Photography has always been about choices. Where to stand, when to press the shutter, what lens to use. These decisions create a personal perspective. When we start replacing skies and other elements with AI-generated alternatives, whose vision are we actually presenting? Is it still photography, or have we crossed into digital illustration?

Don't get me wrong: I'm not advocating for an austere, photographic purism. Tools that save time on tedious tasks like complex selections are genuinely useful, and I want to use them as much as anyone else.

At Adobe Max, for example, the demo I saw of the new Select Details feature – which can isolate hair or tennis racket strings in a single click– looks like being an absolute godsend for retouchers who used to spend hours with the pen tool.

Similarly, the latest intelligent color adjustments, which enable you to modify specific hues throughout an image, streamline what used to be painstaking work.

But still, there's something unsettling about the direction we're heading. When Adobe proudly demonstrates Firefly Image Model 4 creating hyper-realistic portraits from text prompts, or showcases its Generative Extend feature for video that can fabricate footage that never existed, we should pause and consider the implications.

At what point does "enhancing" become "falsifying"? When we replace skies, extend scenes beyond their original boundaries, or generate elements that were never there, we're no longer documenting reality – we're manufacturing it.

This matters because, despite our growing cynicism, photographs still carry an implied truth value that other visual media don't.

A new categorization?

To Adobe's credit, it's developing authentication tools like Content Credentials that can reveal how much AI was used in creating an image. Its browser extension for Chrome enables viewers to see who produced an image, what tools were used, and whether generative AI was involved.

But will these authentication markers become widely adopted, or will they remain a niche concern while AI-fabricated imagery floods our visual landscape?

Perhaps we need to reconsider how we categorize these new hybrid images. A photograph that has had its sky replaced with an AI-generated alternative isn't purely a photograph any more, it's something else – a composite, a digital creation, a photo-illustration.

There's nothing wrong with that in itself, but presenting it as straight photography feels disingenuous.

For professional photographers, these developments raise existential questions. If anyone with a smartphone and the right app can generate perfectly exposed landscapes with ideal lighting and dramatic skies, what value remains in the technical and artistic skills that photographers have spent years developing?

The democratization of image creation is wonderful in many ways, but it also threatens to devalue the craft of photography itself.

Undermining reality

The most concerning aspect might be how these tools change our relationship with reality. When every sunset can be made more dramatic, every portrait more flattering and every landscape more epic with a few clicks, our expectations of what the world actually looks like may become distorted.

As a society, we risk creating a visual culture where even reality itself seems disappointing by comparison. How many have flown thousands of miles to an Instagram-favorite destination to glory in the sunrise, only to discover that it looks pretty much the same as one back home?

So yes, these new AI tools in Photoshop and Lightroom are impressive. Yes, they'll save time, simplify workflows, and open creative possibilities. But as photographers and image makers, it's up to us to use them thoughtfully, with awareness of where enhancement ends and fabrication begins.

And maybe, just maybe, we could leave a few skies as we actually found them.

You might also like…

Take a look at the best photo editing software and the best free photo editing software – just remember to use them responsibly!

Tom May is a freelance writer and editor specializing in art, photography, design and travel. He has been editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine. He has also worked for a wide range of mainstream titles including The Sun, Radio Times, NME, T3, Heat, Company and Bella.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.