Early Verdict

As we just happened to have one lying around, we thought we’d see how many worlds apart the Nikon FM/FM2 35mm SLRs and the digital mirrorless camera they’ve inspired, the Z fc, are. While these cameras helped build Nikon’s reputation, what you’re buying today is the very different user experience embodied in the classical mechanical 35mm SLR. They demand total involvement and it’s as much about the journey as the destination. Here’s where you can learn the principles of exposure control, of focusing and of depth-of-field… in fact, you have to if you’re to achieve anything. But this purity of purpose is both refreshing and rewarding… you have to work for your results, but it’s really worth the effort. There are both the tactile and visual elements too – the FM look… well, classically classical, which Nikon has managed to very successfully replicate with the Z fc, but the big difference is that these 35mm SLRs are the real thing.

Pros

- +

Classic film camera

- +

Robust workhorse of a camera

- +

Can still work without a battery

Cons

- -

Film adds to running costs

- -

Maximum 1/1000sec shutter speed

- -

Very limited range of features

Why you can trust Digital Camera World

So what do the Nikon FM and the Z fc have in common exactly? Well, in reality, not very much. It’s interesting that Nikon chose the Nikon FM2 – the FM’s successor – as the inspiration for the Nikon Z fc as the two really couldn’t be more different. Even the semi-auto FE and FE2 are a tiny bit closer, but both the FM and FM2 are fully mechanical, and so, obviously, also fully manual.

Both were built uncompromisingly tough, which was partially based on an all-metal construction and partially on the simplicity of a camera using very little in terms of electronics. There’s a built-in exposure meter that requires a battery and drives a simple LED display in the viewfinder, but that’s it. The Z fc on the other hand…

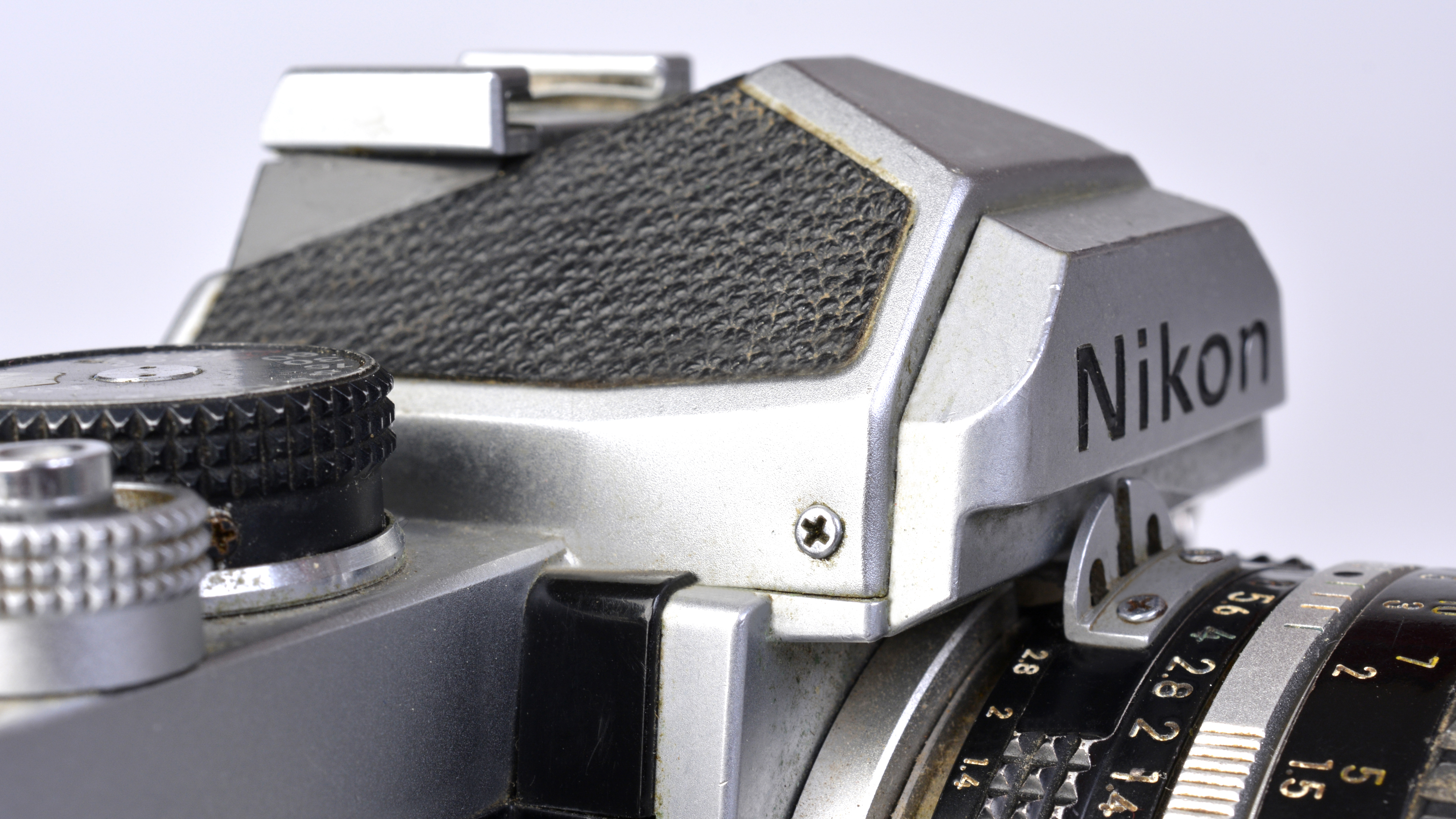

The FM featured here is an old press and sports camera, so there’s plenty of scuffs and scratches, but everything is still working fine… metering, quick-return mirror, shutter and film transport. The viewfinder has a few marks on it too but, since the focusing screen is fixed, it can’t be cleaned properly and you soon learn to live with them. The one casualty of its hard life is that the plastic depth-of-field preview lever has snapped off at some point, rendering this feature unusable.

The shutter goes off with a resounding ‘ker-lunk’ and the subsequent film advance is accompanied by the sound of intermeshing gear wheels. Quiet the FM most certainly ain’t, but it is definitely near indestructible as this 40+ years-old example attests.

The FM was launched in May 1977 and introduced a new generation of non-professional Nikon 35mm SLRs. The “Nikkormat” title – used since 1965 – was dropped in favor of “Nikon”, and there was a completely new and more compact bodyshell with an updated version of the F mount. This incorporated a facility called Automatic Maximum Aperture Indexing – Ai for short – which allowed for the lens’s largest aperture setting to be automatically conveyed to the camera’s metering. Prior to this, the procedure had to be performed manually and required the lens to be first set to f/5.6 to align a ping on the camera body with a coupling prong fixed to the lens’s aperture collar (not surprisingly, at the f/5.6 position). After the lens was attached to the body, the aperture ring was first twisted to the minimum (i.e. smallest) aperture and then to the maximum aperture in order to communicate this range to the meter.

Ai lenses have a shaped ridge near the mount that couples with a lever on the camera body’s side to automatically convey the maximum aperture as the lens is attached. This distinctive, rapid right-left twisting action after attaching a lens had subsequently come to easily identify a Nikon 35mm SLR user even if observed from a distance! However, it was clunky to say the least, and the Ai coupling meant everything was relayed to the metering system as the lens was being mounted. However, the prong was retained on the Ai series Nikkor lenses for a while to maintain compatibility with the pre-1977 bodies. Additionally, these lenses have not one set of f-stop markings, but two; the second being closer to the camera’s mount and with smaller digits that are ‘read’ by a small lens set into the base of the nameplate enabling the set aperture to be shown in the viewfinder.

Nikon maintained the Ai arrangement on its lenses – updated in 1981 to AiS to allow for fully automatic aperture control – right up until the G-type lenses were introduced in 2000 which no longer had a manual aperture collar. However, camera bodies kept the coupling ring on the lens mount well beyond this, although in the digital era this is only the case with the higher-end and pro-level DSLRs (meaning that light metering capabilities are only available with Ai lenses on these models).

Nikon FM: Specifications

Lens mount: Nikon F

Exposure control: Manual

Shutter speed: Mechanical 1/1000 sec to 1 second, plus bulb

Exposure metering: Center-weighted

Battery: Two 1.55V SR44 / 1.5V LR44 batteries

Dimensions: 42.0 x 89.5 x 60.5mm (body only).

Weight: 580g (body only without batteries)

Full metal jacket

Following the FM, Nikon launched the FE in early 1978 and this camera had an identical all-metal bodyshell, but an electronically-controlled shutter with aperture-priority auto exposure control. The FM was replaced by the FM2 in 1982 which, again, retained the same body, but with a new focal plane (mechanical) shutter capable of up to 1/4000 second… then a world first and achieved by using lighter-weight titanium shutter blades. Flash sync was initially up to 1/200 second, but FM2 bodies built after March 1984 had flash sync up to 1/250 second (and are known as the FM2N, although they are still just badged “FM2”).

The FM’s spec was more humble, although pretty much standard for the day – a top shutter speed of 1/1000 second with flash sync to 1/125 second, and centre-weighted average metering driving a basic over/OK/under LED exposure display in the viewfinder. And while there was a growing emphasis on automatic exposure control modes, every major manufacturer still had a mechnical model in its 35mm SLR line-up. For the FM, the main competition was Olympus’s OM-2, the Canon AT-1, Minolta’s venerable SR-T series and the Pentax MX along with the K1000. Nikon’s main emphasis was on rugged reliability, and while the FM was more compact than the previous Nikkormats, both Olympus and Pentax were concentrating on making their cameras as small as possible.

The FM’s bodyshell is cast from an alloy of silumin-copper-aluminum with a tensile strength of 33.5 kg/mm², which very strong indeed. The top and bottom plates are brass, the camera back is aluminum and all the important stuff on the inside – such as the film transport gears – is also made of metal. Weather sealing of SLR bodies was still to come, but there are so few control joints, the FM can cope with a light shower or a bit of spray. Nikon carried on with including a leatherette insert on the pentaprism housing – a design element it had been using since its very first 35mm SLR, the legendary F, which was launched in March 1959. It’s since been reprised on the Df full-frame DSLR and now the Z fc.

The FM’s focusing screen is fixed – interchangeability came with the FM2 – and provides a split-image rangefinder with a microprism collar. The feature set is distinctly no-frills – depth-of-field preview, a multiple exposure facility, self-timer, cable-release socket and flash hotshoe supplemented with a PC sync terminal and… er… well, that’s it. Oh yes, there is a film memo holder on the camera back which is where you put the torn end of the film carton to remind you what you’ve got loaded (and replicated digitally on Fujifilm’s X-Pro3).

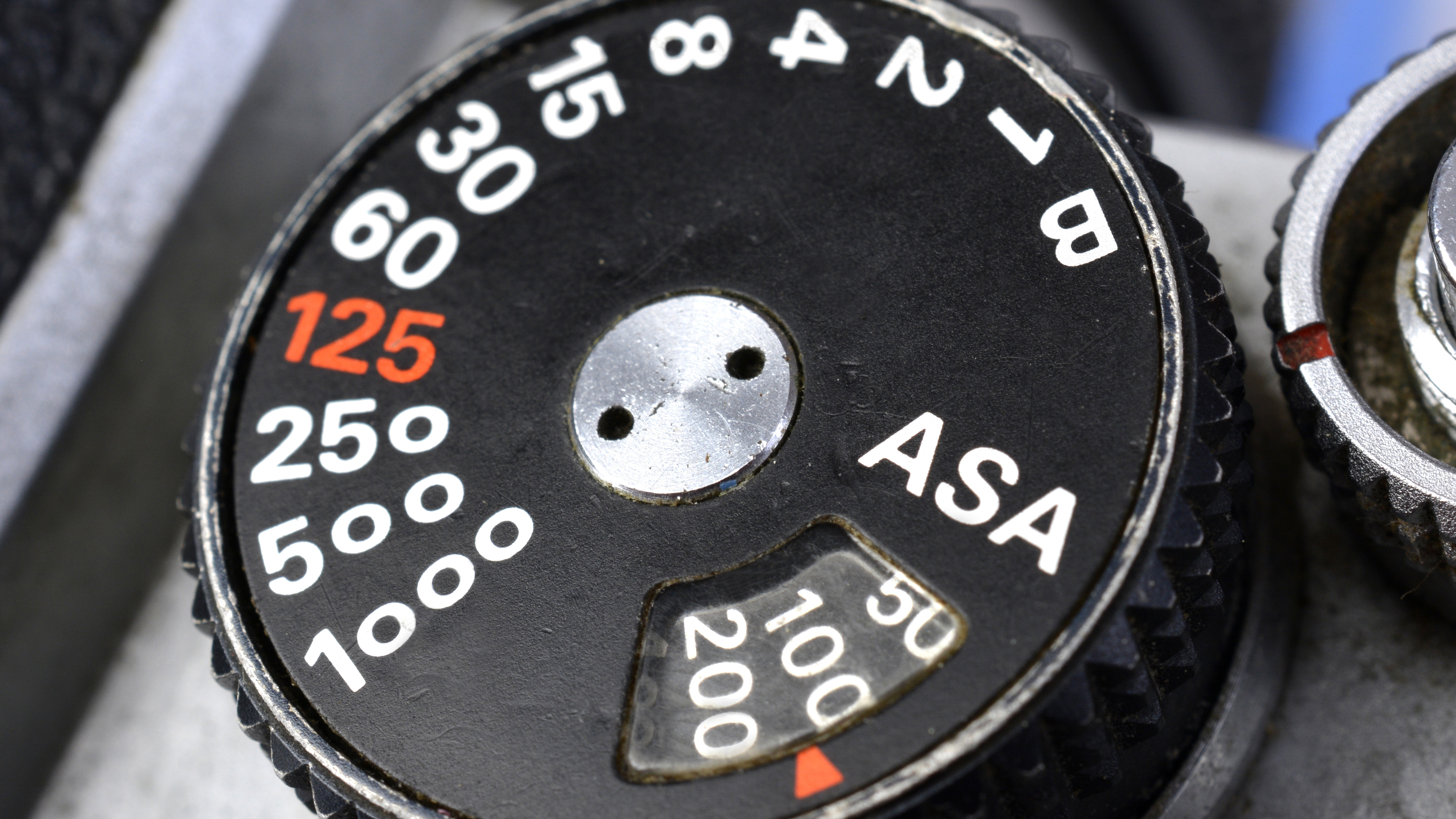

The ISO – then called ASA – setting range is from 12 to 3200, but back in 1978 ISO 400 was considered the limit for colour negative film and ISO 200 for color transparency film (Kodak Ektachrome 200 was introduced in 1977) as sensitivity was linked to the size of the silver halide crystals and so-called faster films were very grainy. When Kodak introduced Ektachrome P1600 increase sensitivity without adding grain so, by the 1990s, ISO 800 color negative films performed well enough to be offered as both amateur and professional products. There were a number of ISO 1600 colour neg films too, but these were lower in colour saturation with increased grain and significantly reduced exposure latitude. In B&W, Kodak’s T-Max P3200 led the way in faster monochrome films but, again, was actually really ISO 800 pushed two stops when developed. In comparison, Ilford decided to make graininess a feature of Delta 3200, which was essentially an ISO 1600 emulsion that could be both pushed and pulled in development (incidentally, both these films are still available). In practice though, many photographers rarely used anything faster than ISO 400 and, when the FM launched, slower films such as Kodachrome 25 and Kodak Technical Pan (which was also rated at ISO 25) were still popular.

Handling

Not surprisingly given all the metal used in its construction, the FM boasts a reassuring heft, but doesn’t feel excessively heavy as the earlier Nikkormats do. There isn’t a handgrip, which was common for the time, but the camera is still comfortable to handle and feels well balanced even with longer and heavier lenses – such as a 300mm f/2.8 telephoto – attached.

Being fully manual, the FM works entirely on your inputs of ISO, shutter speed and aperture plus, of course, focus. You’re it, and indeed these are the only controls in 1992 it was in fact an ISO 400 speed film that was pushed two stops during development in order to minimise graininess. Various technologies were employed to since varying exposure for visual effect is also entirely in your hands. Everything you need to know is provided in the viewfinder with the focusing aids, the LED exposure display – which simply shows plus, OK or minus – and read-outs for both the aperture and shutter speed. Additionally, the shutter speed is shown right there on the dial, along with the film speed setting. The light meter is activated by pressing the shutter release to its halfway position and then stays active for 30 seconds, which Nikon considered “long enough” for “the creative-minded photographer”. The meter is the only aspect of the FM that requires power. White balance is taken care of by selecting either daylight- or tungsten-balanced film and then using colour correction (CC) filters on the lens.

The one luxury is the facility to fit a motordrive and the FM was launched with the MD-11 – it’s good for 3.5fps, but needs six AA-size batteries to do the job. The FM can also be fitted with the later MD-12 that was launched with the FM2 and requires eight AA-size batteries, adding substantial weight to the camera in return for auto film advance (but you still need to rewind manually) However, you do get quite a nice handgrip to better manage the additional bulk and weight.

Loading film is something photographers soon could do blindfolded and provided the leader was correctly threaded on the take-up spool at the start was very rarely problematic. There was, however, always the risk of accidentally opening the camera back mid-roll (or before rewinding) and fogging all the exposed frames, so Nikon made this less likely to happen with the FM. The back is opened by lifting the film rewind crank, which pops the lock, but the FM has a locking ring that needs to be operated first, making it less likely that you’ll make this mistake (although it’s likely everybody did it at least once during their time shooting film).

Not surprisingly, the FM and Z fc don’t actually have a lot in common. Ironically, the modern mirrorless camera actually has more dials than the 35mm SLRs that have supposedly inspired it, and the handling is sort of similar. Of course, you can use the Z fc in manual mode with centre-weighted average metering should the mood take you, but the chasm between it and the FM/FM2 is immense… mirrorless-versus-reflex and digital-versus-film just for starters. Even in its day, the FM appealed to the traditionalists who trusted mechanical over electronic and manual over automatic. They liked to be in complete control and didn’t want anything other than the true basics of exposure and focusing… Nikon called it “command photography”. The closest thing to this in the digital camera world is probably Leica’s M10-D.

Speed and performance

Mechanical cameras were tested for the accuracy of their shutter speeds which could vary quite considerably at the faster settings. It was why getting to 1/1000, 1/2000 and then, finally, 1/4000 second was often celebrated in a 35mm SLR’s model number. Nikon worked hard to get the FM2’s shutter to reliably deliver 1/4000 second every time (and over time), designing titanium blades that were further lightened by using a honeycomb pattern etched onto their surface. Distrusted by the purists, ironically electronically-controlled shutters were very much more accurate and eventually allowed for a top speed of 1/8000 second.

Metering reliability was also tested and both the FM and FM2 scored well here, even though the older model uses the less sensitive gallium arsenide phosphide (GPD) cells which were changed to silicon photodiodes (SPD). Nikon opted for a 60% weighting on the central zone which had a 12mm diameter and provided a good balance in a great many shooting situations.

Unless you fitted the motordrive, the FM’s shooting speed was down to how quickly you could drag the film advance lever through its 135º arc. Some 35mm SLRs employed a clutchless design, so film advance could be completed via a series of shorter strokes, but the FM’s lever is single-stroke, so you have to go all the way. It’s debatable which was any faster in the end. Focusing accuracy is also down to you, but the split-image rangefinder is exceptionally accurate and was retained even when autofocusing became the norm.

Image performance is, of course, largely a product of the film you use, but as ever, the lens plays an important role. For decades, if you bought a 35mm SLR with a lens, it would be the standard 50mm prime in whatever speed you could afford… there were f/1.2, f/1.4, f/1.8 and f/2.0 Nikkors, plus a 55mm f/1.2 which was available as an Ai lens when the FM was launched.

A camera like the FM/FM2 was ripe for accessorizing, which was where photo retailers often made their money… motordrive (or autowinder), data back, flash unit, filters and a cable release. And no self-respecting sales person would ever have let you leave the shop without first trying to sell you an additional lens, a camera bag or a tripod.

Nikon FM: Verdict

Both the FM and FM2 were big sellers, the latter model staying in production from early 1982 until 2001 with two upgrades along the way – the FM2N in 1984 which lifted the maximum flash sync speed to 1/250 second while, in 1989, the titanium shutter blades were replaced by aluminum ones that could now be made just as lightweight, but were more durable.

Consequently, both models are plentiful on the secondhand market, but their overall reliability and long-term durability – not to mention the desirability of manual-focus Nikkor lenses – are keeping prices buoyant.

While these cameras helped build Nikon’s reputation, what you’re buying today is the very different user experience embodied in the classical mechanical 35mm SLR. They demand total involvement and it’s as much about the journey as the destination. Here’s where you can learn the principles of exposure control, of focusing and of depth-of-field… in fact, you have to if you’re to achieve anything. But this purity of purpose is both refreshing and rewarding… you have to work for your results, but it’s really worth the effort. There are both the tactile and visual elements too – the FM and FM2 look… well, classically classical, which Nikon has managed to very successfully replicate with the Z fc, but the big difference is that these 35mm SLRs are the real thing.

Read more:

• Best film cameras

• Best film

• Best darkroom equipment

• Best film scanners

• Best Lomography cameras

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.