Digital Camera World Verdict

The original Polaroid OneStep was one of the biggest selling cameras of the 1970s and the new camera replicates the retro shooting experience brilliantly. However, in the digital era it’s more of an enjoyable curiosity than anything else.

Pros

- +

Fun factor

- +

Classic Polaroid instant prints

- +

It’s a future collectible

Cons

- -

Polaroid Originals film is expensive

- -

Every shot is printed

- -

Development times are quite long

Why you can trust Digital Camera World

What is it about Polaroid that seems to resonate with us so strongly? Despite many ups and downs since the original company’s demise in 2001, the brand has retained both recognition and reputation. Yet the sales of Polaroid-branded cameras today is a mere fraction of the glory days back in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.

And virtually nobody is using Polaroid films to test for exposure, lighting or composition any more. It surely can’t all just be about sunglasses, can it? Even in the digital era, the idea of an instant camera has remained appealing, enough to keep Fujifilm’s Instax business ticking along nicely and convince other camera brands – including, remarkably, Leica – to get involved.

Lens: 103mm f/14.6 single-element.

Focus: Fixed from 122 centimetres to infinity.

Exposure: Automatic programmed via adjustable shutter speeds from 1/3 – 1/200 second and apertures from f14.6 to f45.

Flash: None built-in. Accepts bulb-type Flashbars or Polaroid Q-Light electronic flash unit.

Dimensions (WxHxD): 110x95x141 mm.

Weight: 390 grams (without film pack).

Yet even here, it’s still the classic Polaroid products that have most stirred the emotions of photographers, resulting in thriving businesses refurbishing, in particular, the legendary SX-70 camera and, of course, the establishment of the hugely ambitious and aptly-named, The Impossible Project. Back in 2008, an organization of enthusiasts took over part of an old Polaroid production facility in The Netherlands, and set about reviving the best-loved Polaroid instant print films, SX-70 and Type 600.

The challenge here was that, without access to the original patents and formulations, they had to start from scratch and attempt to achieve in just a couple of years what took Polaroid’s founder Dr Edwin Land virtually a lifetime. There’s been mixed success, but perhaps most importantly The Impossible Project kept the Polaroid dream alive, even attracting new aficionados along the way.

History has a strange way of taking unexpected turns and so it came to pass that a Polish entrepreneur headed a syndicate which, in May 2017, purchased the company which owns the Polaroid brand and, importantly, all the associated rights. Wiacezlaw Smolokowski also happens to be the largest shareholder in The Impossible Project so, very neatly, the will and wherewithal have been combined.

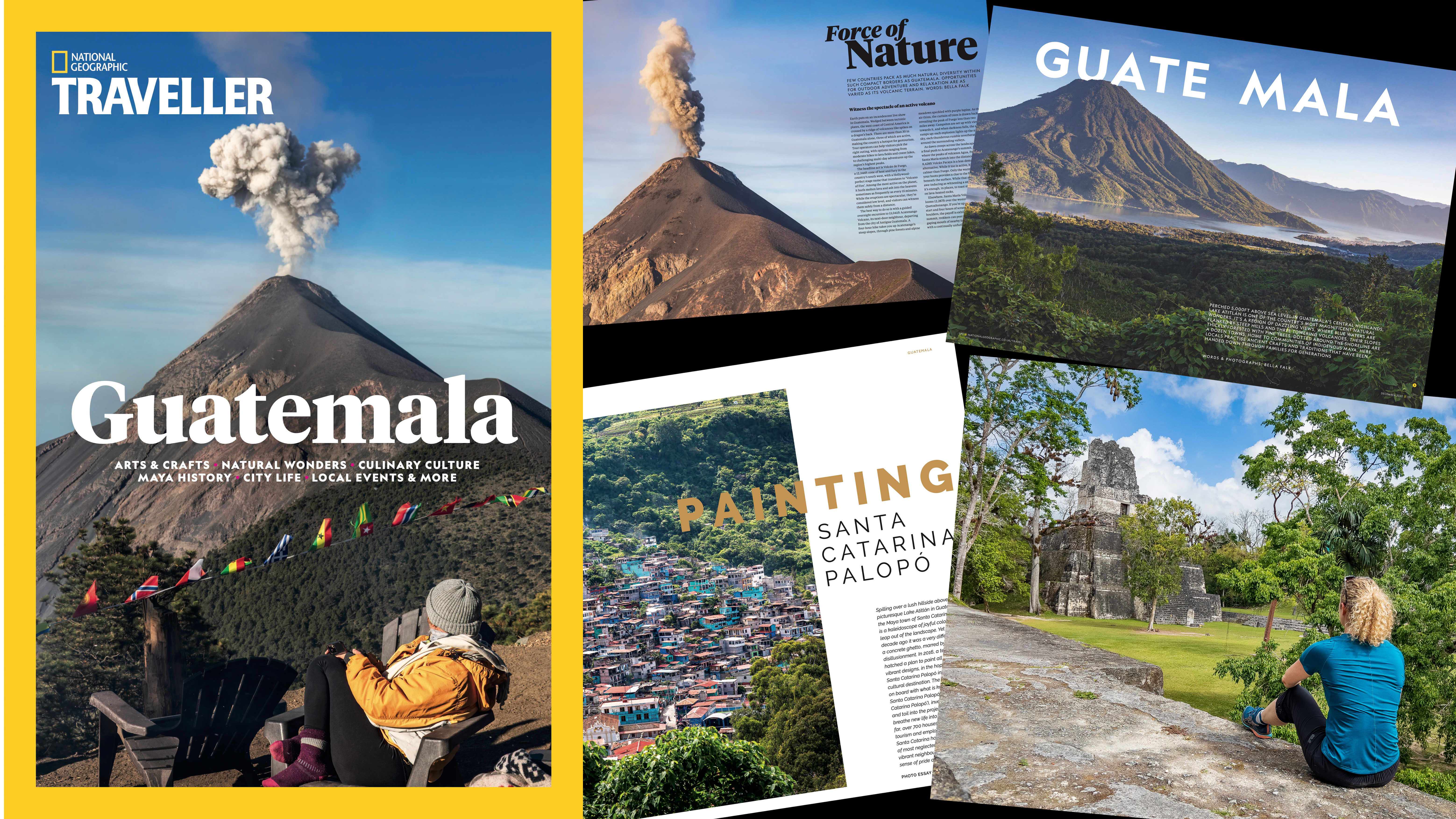

The first fruits of this marriage are a revival of the OneStep camera – a cheap-and-cheerful box-type model hugely popular in the 1970s – and the rebranding of The Impossible Project as Polaroid Originals.

The new OneStep 2 has already been a success in its own right, rapidly selling out after it was first announced and remaining in short supply until recently. There’s also a new instant film called i-Type, available in both colour and B&W, which replicates the square format of the classic SX-70 and Type 600 prints.

Polaroid Originals has also taken over all the Impossible Project products, including the various films it had re-created and its range of refurbished vintage Polaroid cameras.

Keep It Simple

The original OneStep, unveiled in 1977, was billed as “the world’s simplest camera” because all you had to do was press the shutter button… and the camera did the rest. There were no controls, not even an on/off switch and, while there was an adjustment for exposure, you didn’t necessarily have to use it. The print was automatically ejected via a motorized transport and was self-developing, a big advance on the previous peel-apart Polaroid materials.

Initially, the OneStep cameras used the SX-70 print film, but moved on to the improved Time Zero series film in 1981. In the mid-1980s, the name was carried on, but on a new generation of cameras which used the faster Type 600 film as part of a new balanced daylight-and-flash auto exposure system. Type 600 film is rated at ISO 640 versus SX-70 film’s ISO 125. As it happens, the original OneStep will physically accept 600 Series film packs after they’re very slightly modified, but it’s then necessary to reduce the exposure by two stops by using a neutral density (ND) filter over the lens. Fiddly, but possible.

Unlike the revolutionary SX-70 camera (introduced in 1972) which had a novel folding design, the OneStep was rigid-bodied to reduce manufacturing costs and make it easier to use. Over the years, there were many variants, some specific to certain markets and with different model numbers (for example, the 1000, 1000S and 1000SE in Europe). The basic fixed-focus lens was upgraded to zone focus in the later models and then stepped up again to Polaroid’s sonar-type autofocusing (introduced on the SX-70). Additionally, there was a choice of black or white body colours and a few subtle styling variations such as a round or square lens housing and either red or green shutter buttons.

The OneStep spearheaded Polaroid’s very successful sales strategy of pricing its consumer cameras extremely affordably with the profits coming from the consumables, namely the film. It worked, and in its first year on-sale, the OneStep became the best-selling camera in the USA. Interestingly, Polaroid manufactured the OneStep cameras itself at one factory in Massachusetts and another in Scotland (it also had plants for making film, batteries and sunglasses, and this heavy investment in manufacturing would eventually prove problematic down the track).

Over The Rainbow

The OneStep was also the first camera product to carry the iconic rainbow stripe (eventually officially called the Polaroid Color Spectrum) which had previously been used on Polacolor film packaging since 1968. It subsequently became part of Polaroid’s corporate logo and branding, surviving the various changes of ownership which have taken place since 2001. A slightly restyled version has now been adopted by the new Polaroid Originals company.

An all-plastic construction – including the one-element lens – and fixed focusing helped keep the price down, but the OneStep still had built-in metering with automatic exposure control via an electronic shutter and lens diaphragm. In the USA, it sold for $39.95 which, given the comparatively sophisticated exposure control system – at least for a snapshot camera – can’t have left much room for any profit margin at all. Power came from an ultra-slim, six volt battery – another piece of Polaroid engineering genius – housed in each SX-70 film pack, an arrangement that was continued with the later Type 600, Spectra, Captiva and Vision films.

Not surprisingly, the OneStep 2 has the more modern arrangement of a built-in rechargeable lithium-ion battery pack (with in-camera charging via USB cable no less), but it will accept Type 600 films, both new and vintage, but whether it switches to using the pack’s power supply is unclear, especially as there’s a voltage difference between the two sources. Presumably one challenge that Polaroid Originals could well do without, is that the new i-Type films (again rated at ISO 640) don’t have built-in batteries and so the boxes are boldly marked “Not for Vintage Cameras”.

Retro Repro

If the original OneStep’s specifications aren’t especially detailed (even with the benefit of history), they’re positively encyclopedic compared to what’s been published about the new model.

The lens – made from optical-grade polycarbonate and coated to reduce flare – has a focal length of 106mm (roughly equivalent to 40mm) and again the focus is fixed, this time from around 60 centimetres to infinity.

The aperture range isn’t known, nor the shutter speeds, but exposure control is programmed to some extent, including again balancing flash and daylight. According to Polaroid Originals, the shutter is a “custom design using [a] precision step motor”, but that’s as much as they’re giving away.

The built-in flash is the biggest change over the original, which only has a dedicated port – shared with the SX-70 – for fitting either a ‘Flashbar’ module which housed ten flash bulbs (five on each side) or the accessory Q-Light electronic flash unit. Incidentally, the latter has been re-created by MiNT and is available from Polaroid Originals.

Beyond the built-in flash though, the OneStep 2 is a pretty faithful reproduction of the original mainly because, of course, the basic shape still has to be the same. The new bodyshell is a combination of polycarbonate and ABS plastics with the choice of white or black finishes. And the white really is white, unlike the original which was more of a pale grey color. However, the rainbow logo is reduced to just a small block rather than the full-blown ‘racing’ stripe which would have just finished things off nicely. Nevertheless, there’s no question the new camera looks spot-on in terms of beautifully re-creating the nostalgia, but with a 21st century smartening-up of the styling.

The shutter release button is regulation bright red, but exposure adjustment is now by a small sliding switch rather than the original’s rotating knob (although this is replicated in miniature to still house the metering cell). There’s an on/off switch – something the originals didn’t need because of the film pack-based power supply – a button for the self-timer and another button to override the flash (which otherwise will always fire, providing fill-flash in brighter conditions).

Surprisingly, the new camera’s viewfinder is a lot harder to use as it doesn’t have the extended eyepiece of the original which ensures your cheek clears the sloping back of the camera.

The OneStep 2’s finder is bigger, but this really doesn’t mean much when you have to tilt your head at an awkward angle to actually use it.

Counting The Cost

Film packs load through the front of the camera in the traditional way, but instead of an analog frame counter, the OneStep 2 uses a nifty arrangement of eight orange LEDs – located in a 4x2 pattern on its top panel – which extinguish one by one to show how many unexposed prints are remaining.

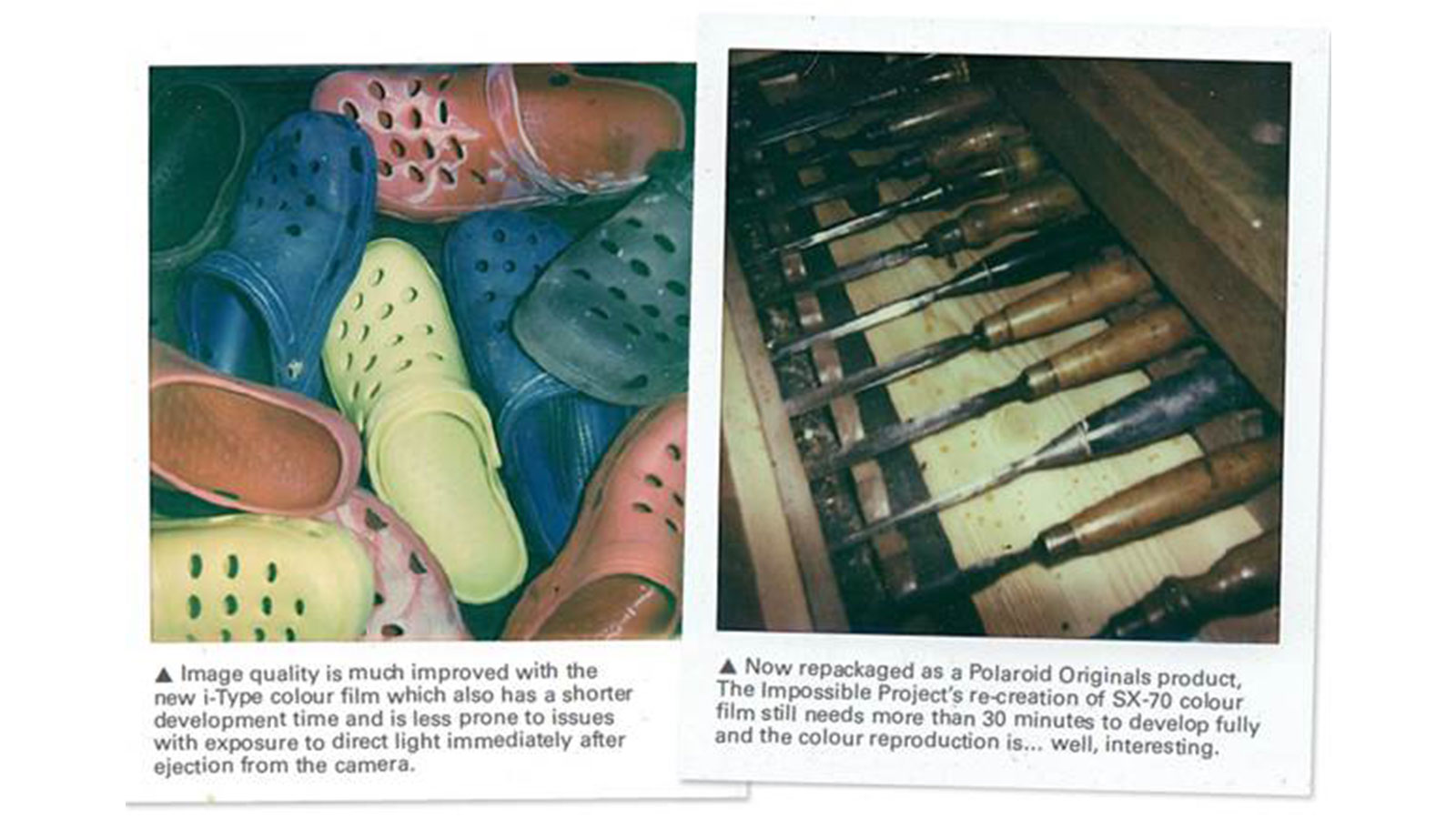

Print ejection is motorized, but while the SX-70 cameras simply spat one out and development began immediately, it’s a bit more complicated with the Polaroid Originals film. After taking the shot, a flexible protective cover unfurls from the camera to prevent the exposed print being instantly dosed with available light. You then need to place the print face down (and away from direct light) to await complete development which is now thankfully shorter than the 30+ minutes required by The Impossible Project films, but still longer than we suspect Dr Land would have approved of.

That said, the new i-Type colour film is a significant improvement, not just in terms of the shorter development time and reduced susceptibility to direct light exposure post-camera, but also the image quality, notably both the colour saturation and the contrast.

The “i” apparently stands for “incredible” which is a bit of an overstretch, but things are definitely looking up compared to the valiant but problematic early IP products (and, in fact, should now only get better). Of course, you get the classic Polaroid instant print format – the product of the developer pod’s location – which is sized at 8.8x10.7 centimetres with a square image area of 7.9x7.9 centimetres. This is quite a bit larger than Fujifilm’s new Instax Square film which has an image area of 6.2x6.2 centimetres, but i-Type film is significantly more expensive, working out at $4.85 per print versus $2.75 (based on digiDIRECT’s current pricing). At this sort of cost, it’s hard to see the OneStep 2 being quite the party camera that made its predecessor so popular, and its usage is likely to be more circumspect… even artistic (although a refurbished SX-70 is perhaps a better option here, currently around €400 from Polaroid Originals).

Verdict

Fun, fun, fun. Forget any rationalization and just enjoy the experience. Even if you aren’t a classic Polaroid camera enthusiast, the OneStep 2 is still strangely appealing and while it’s never going to match its predecessor’s sales success, it has the potential to be every bit as significant in historical terms (so, if nothing else, it’s already a nice collectible). Polaroid is back – properly so – and the OneStep 2 is just the start of a much more significant renaissance than The Impossible Project has been able to achieve despite its commendable efforts so far. Perhaps more importantly though, it’s the continued improvements in the film products – now more certain than before – that are likely to make this and any future Polaroid Original cameras something more than just nostalgic curiosities. SX-70 Mark II anybody?

Read more:

The best instant cameras today

Best digital instant hybrid cameras

Best portable printers for photos

The best camera for kids in 2020: child-friendly cameras for all ages

Australian Camera is the bi-monthly magazine for creative photographers, whatever their format or medium. Published since the 1970s, it's informative and entertaining content is compiled by experts in the field of digital and film photography ensuring its readers are kept up to speed with all the latest on the rapidly changing film/digital products, news and technologies. Whether its digital or film or digital and film Australian Camera magazine's primary focus is to help its readers choose and use the tools they need to create memorable images, and to enhance the skills that will make them better photographers. The magazine is edited by Paul Burrows, who has worked on the magazine since 1982.