Baked Beans on Weetabix? Tweet the tastiest pic with these food photography tips!

Social media has gone crazy for Baked Beans on Weetabix – here's how to share your best shot!

Baked Beans on Weetabix has gone bananas on social media, thanks to a brilliant bit of marketing by two giants of the breakfast food business. Twitter has exploded with people hashtagging, snapping and sharing shots of their own beans and 'bix concoctions – but if you want your tweet to trend, you'll need to take something worth retweeting!

That's where some classic food photography tips come into their own. Yes, the current hashtag mania is a bit of silly fun, but that doesn't mean it's not worth taking a bit of time to set up a proper shot and do things properly – and a great photograph is far more likely to go viral than a grainy snap on your phone!

Food photography has taken on a new lease of life in recent years. No longer is it the niche preserve of cookbooks and the menus at cheap restaurants – social media has made food photography one of the most popular genres in the art form, with the cooking (and even eating) of the meal often being secondary.

• The best lenses for food photography

• The best books on food photography

Photography projects at home

• More home photography ideas

Useful home photography kit

• Best tripods

• Best lighting kits

• Best reflectors

• Best macro lenses

The current lockdown situation makes food photography an even more appealing choice for frustrated photographers unable to head into the real world. With little more than your core camera kit and your kitchen surfaces, you can create some truly tasty looking shots.

While the general principles have much in common with still life and product photography, shooting food has plenty of pitfalls all of its own. Either way, you will need solid foundations of photographic theory and technique – and obviously practice makes perfect! Just like cooking up your favorite dish, getting things just right can be a lot more complicated than it seems.

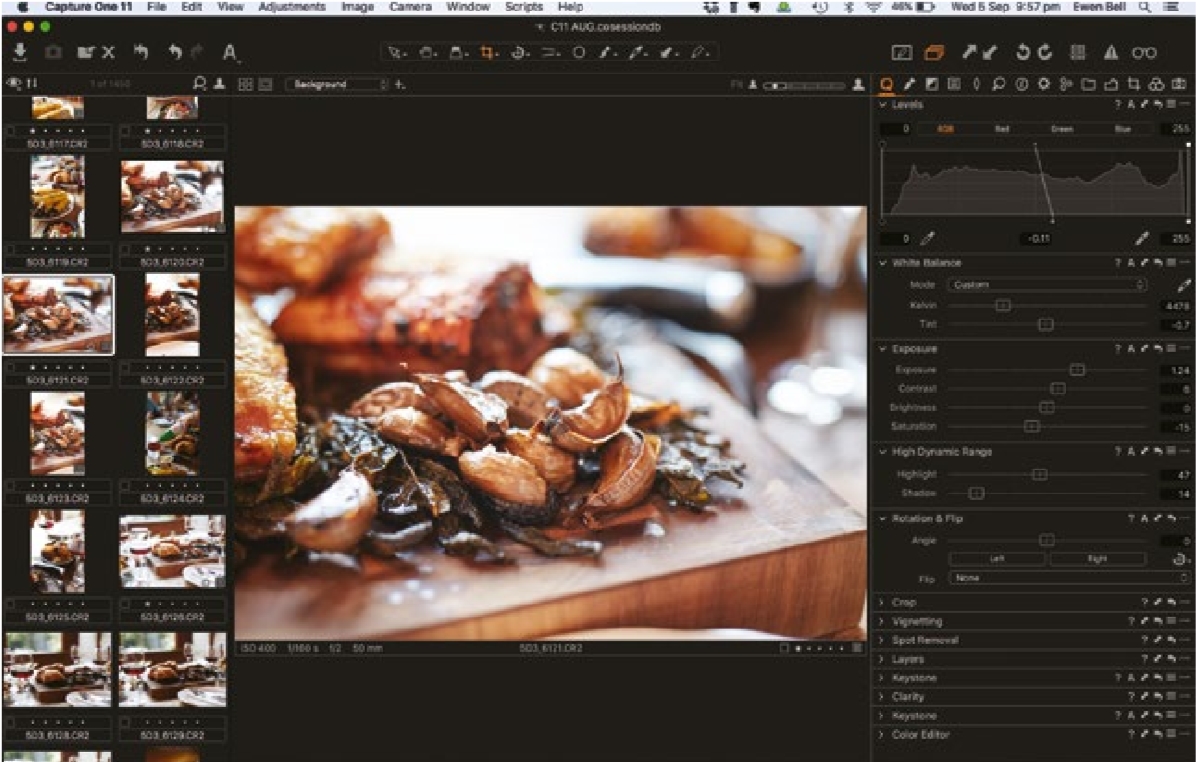

To get you on the right track with capturing your culinary creations, we popped into the kitchen with professional food photographer Ewen Bell to examine both the equipment and the key skills to get shots that are as much a feast for the eyes as they are for the stomach…

Why should bread have all the fun, when there's Weetabix? Serving up @HeinzUK Beanz on bix for breakfast with a twist. #ItHasToBeHeinz #HaveYouHadYourWeetabix pic.twitter.com/R0xq4Plbd0February 9, 2021

1. Work in good light

The most common mistake is trying to shoot beautiful food in bad light. Cameras see light, not subjects, even when that subject is delicious!

Food photography always begins with the light. The perfect light is soft, abundant and angled. You want lots of light to play with, but you definitely don’t want direct sunlight streaming onto the scene; it’s too harsh and too contrasty. The best table in the restaurant has the window seat, with bright daylight outside and only filtered light coming through.

This scenario turns the window into a large softbox, filling the table with useful light that offers a range of shooting angles. The starting point is to shoot at an angle across the light source. That angle gives sufficient contrast to reveal detail in the scene, and brings up the colors. You don’t have to fill in the opposite side of the scene with a bounce board, or fill-in flash, because you can brighten underexposed areas of the raw images when you process the files – it’s often quicker and more precise to fine-tune the raw files than trying to get it perfect in-camera.

As you change your angle, you create a different quality of light for the scene. The more you shoot into the light the more contrast and drama you build. Color richness gets reduced, blacks are hardened and some areas might even blow out, and that’s acceptable for the purpose of style, if drama is what you’re looking for.

Alternatively, when you change your angle to have light coming a little more from behind you, the scene fills in more and the contrast flattens out. By controlling the angle at which you shoot relative to the window, you control contrast and color as well – even when the light is very, very soft.

It won’t matter how amazing your food looks on a plate if the light isn’t working for you – good food in bad light makes for failed photos. In the right light, on the other hand, almost any scene can be made to look inviting.

2. Editing your shots

The treatment of your Raw files is just as important as the shoot. The most natural colors often result from going easy on the saturation, or even pulling back on it a little; if you’re struggling with color balance, it’s likely that you have the saturation dialled up too high.

In very flat light you may need to bump contrast a little in order to give hardness to edges – adding contrast only at the blacks end of the histogram will help to preserve tones elsewhere in the scene.

Additionally, shadow detail can be lifted to balance out the scene. Be sure to use selective adjustments to add exposure or more shadow detail if critical elements are lost in shade.

3. Consider flash

The problem with relying on natural light when shooting food is that it isn’t always that natural. Color casts can be thrown across the scene by trees outside, interior lights can add color spots to the room, and the movement of clouds throughout the day can cause dramatic changes to contrast and color temperatures.

You’ll never get a nice, clean white light unless you bring your own. Flash gear will bring consistency to your photography and reduce processing effort. Reliable strobes deliver the exact color and quantity of light from one frame to the next. If you’re shooting content across several days but need the look and feel of each frame to be consistent, then studio flash is the way to go.

Aside from being very practical and reliable, once you get your flash gear under control you’re freed up to concentrate on your creativity. Scale is critical here. Just as we enjoy soft, abundant, angled light in the window seat of a restaurant, we try to achieve that same result in the studio.

A large softbox is required, powered by a sufficiently capable light source. 100W of flash is more than enough to shoot a table scene and pull out moments of inspiration within it.

Battery-powered flashguns can do the job, but you’ll burn through the batteries, and they’re painfully slow to regenerate as the power drains. For the same price as a decent flashgun you can buy monoblock kits that offer a plug-in unit with a inbuilt receiver; just connect to the mains power and slip the trigger unit onto your camera, and you’re ready to go.

A reliable light source is essential, and so is consideration for how you want to shape the light. Softboxes for food photography should be very large, and offer generous amounts of internal diffusion. You need to get the softbox close to the scene, as close as possible to keep the light as diffused as possible.

If your light-shaping boxes are not soft enough, and too much contrast is coming through to the scene, simply add an additional diffusing screen between the food and the flash.

4. Stop motion

Consistent lighting from studio flash gear is perfect for making short stop-motion clips of the step-by-step assembly or presentation of a dish.

Lock down the camera on a tripod, and lock off the focus and exposure – you need these to be the same for every scene. Make small adjustments between frames to mimic a scene in motion.

Process the raw files to perfection before you output the individual frames, then bring the stills into your video-editing tool, and use soft transitions to smooth the motion.

5. All the magic happens at 50mm

The field of view from a 50mm lens is the sweet spot for still-life photography, including food. As your field of view goes wider, such as 35mm, you start getting perspective issues, and the wider you shoot the closer you need to get, which can further exaggerate perspective. It also gets difficult to control the background with a wider lens; you don’t always want the rest of the room to be drawn into the frame.

Narrowing the field of view with a telephoto lens can be a problem too. Longer focal lengths, such as 100mm, will compress the scene – you can lose the sense of depth, and your compositions can look flat. Longer lenses also create logistical problems when you’re working in confined spaces, as you may not have the room to step back far enough for a shot.

Everything works much better when you start with 50mm. If you’re shooting on a full-frame sensor the other advantage of 50mm is that there are lots of affordable primes on the market.

An aperture of f/2 is ideal, and it’s tempting to use a 24-70mm f/2.8 if you already have one, but then you won’t be t enjoying the full effect of a prime lens at f/2 – and you also have to deal with a big, clunky lens which can be a drag on your creative process.

The equivalent lens for APS-C cameras is a 35mm f/1.4, or for micro four thirds cameras a 25mm f/1.4. the smaller your camera sensor, the greater the depth of field you get at a given f-stop, so you may want to experiment with going all the way to f/1.4 instead of f/2 with these smaller camera bodies. The difference between f/2 and f/2.8 is significant for background bokeh, and it’s even more pronounced at f/4.

Shooting shallow is about bringing attention to one element in the scene, and the degree to which you melt away the rest of the scene is essential to your composition.

Your depth of field expands as you step back from the subject too, so the bigger the scene you shoot at 50mm, the further south you may have to drop the f-stop to get the desired degree of blur.

Shooting at f/4 might look dramatic when your frame is the size of a tea cup, but it offers zero impact once you step back to capture a full table setting.

6. Consider scale

We have a tendency, when we have a lens in hand, to keep stepping inwards, trying to tighten the composition by cutting out all the things we don’t want in the scene. This is a reductive process. We end up with very simplistic compositions, and no idea where we went wrong.

The trick to building richer and more detailed compositions with still life and food is to step back and bring more into the frame, not less. It’s not just a matter of a different lens, it’s a different perspective; thinking bigger is better. We get obsessed with what’s on the plate, without realising that there’s a bigger scene on offer.

As you step back a little you find yourself shooting the table, not the dish. Now you have options for your compositions. Step back a little further and you have a restaurant, not just the table. At each level of scale you get different options for composition.

Stepping back lets you put the dish into a bigger context, with room to include a sense of place. When working in the studio, it’s a common mistake to keep the scale small. Limiting yourself to a fraction of a bench, or a small piece of plywood you painted to look like weathered timber, is limiting your creativity as well.

For big results you need to think bigger than a bread box. Expanding the scale of your shoot zone also enables you to make room for multiple dishes. One plate offers far fewer options than two or three.

With multiples of the same dish on a table or studio bench, you create the potential for layered compositions. As you move around you’ll find shots within the scene, and those multiples of a dish give you multiple moments of inspiration.

7. Include a little action

Still life doesn’t have to be still when it comes to food. Get a little movement into the scene, and bring it to life. Capturing motion within your scenes adds impact to good composition – for example the pouring of liquids, steam rising off hot dishes, or simply the sprinkling of salt onto a dish.

Additionally, the preparation of food, and the people who prepare it, are great elements to include in a photo series. Messy is magic; a sense of the chaos in a kitchen, or ingredients on a workbench, add interest.

8. Style the shot

Building an interesting composition requires a spectrum of approaches, with food styling at one end and photojournalism at the other. You can either create the exact scene you want from scratch using props and styling, or you can look for moments within a scene that already exists in the real world; the best results often come from a combination of the two.

Styling is a dedicated skill – on a commercial shoot the stylist can actually earn more than the photographer. Stylists supply their props and ideas, and typically the concept of the overall shoot rests most heavily in their hands.

The photographer will have to take their lead, manipulate the light to their advantage, and ensure that the final scene is technically competent.

As a photographer, it’s a joy to work with a good stylist, because they carry so much of the creative load. With the stylist preparing the scene, you’re able to devote your attention to the task of finding the ideal composition – for one person to be handling both the photography and the styling can be demanding, as your brain is jumping between two tasks and you may not be able to successfully complete either to your satisfaction.

When you’re shooting on location it’s important to consider how much of the original character from the restaurant or kitchen you want to pull through into the images. Photojournalism imperatives dictate that you reveal the nature of your subject, while styling is an attempt to create it through art. In practice there is always a degree of both.

I like to ‘shoot around the scene’ when I visit a restaurant or other location. I ask the staff to set tables as they would for guests, and to present dishes with wines poured – I want to see how they present their work. With a fully dressed table I then start to look for elements within the scene.

I seek out a ‘hero’, and dig out compositions that pull through multiple elements. And then I might start styling the table a little – not a lot, just a little. I make adjustments, I remove distractions, and I add layers to the background. I do this with location shoots, and when working with a stylist in the studio.

Bringing these two approaches together yields diversity in the images you’re able to collect, and opens the door to innovative compositions that are unexpectedly rewarding.

9. Remember to use props

The key to great food styling is having props on hand to complement the scene. If you’re planning to shoot a lot in the studio, you’ll want to start collecting some interesting props to spice up your scenes.

Ingredients to a recipe can be used as props, as well as crockery and tableware. People can act as props too. Think about hands involved in the scene, or perhaps kitchen staff handling a dish – scaling out to shoot wider allows room to bring those props into the composition.

The right prop can add context to a scene, like a pot of tea and cups alongside a slice of cake. Props can also be used to carefully add specific colors to a scene that embellish the main subject.

10. Take full control

What makes food photography so different to other genres is the degree of control you have over the subject. You can do just about anything you like to the scene – you can even eat it! It’s easy to control the light over a scene the size of a table, compared to shooting a full studio set or waiting for sunrise over a landscape.

Food doesn’t have to pull a pose or deliver an expression; it sits there and silently accepts the attention without moving. Within limits of course – do be careful with ice cream, as it can melt in minutes if you’re not ready for the shot.

The scale and inanimate nature of food photography means you have excellent opportunities for composition. It’s a great genre for exploring the use of color, perspective and repetition.

Don’t feel that you need all the colors of the rainbow jammed into a single frame – instead try initially working with a limited color palette, and find ways to repeat colors through the scene. And use more than one dish in your styling, taking advantage of a bigger scale and bigger ideas.

Change your perspective as you shoot – try the top-down view, but then look for different angles that reveal more or less of certain elements.

Food photography lends itself to tethered shooting, and it’s a good idea to work with a laptop and tether cable when in the studio or on location. It’s a big advantage compared to viewing on-camera only, because you get much better feedback on subtle variations in your shots, and more accurate confirmation of where your shallow depth of field is hitting.

Additionally, the clarity of a large laptop screen also gives you better renderings of your compositions, complete with your preferred processing treatment as each frame rolls off the camera. the prime rule, though, is to always start with the light – it doesn’t matter how interesting the food is if you don’t have good light. Aim for soft, abundant, angled light.

As you change your perspective you can also change your angle of light – like adding salt and pepper to season a dish, changing your angle is fine-tuning the feel of the shot.

Read more:

The best macro lenses

How to take photos magazines and companies want to use

215 photography techniques, tips and tricks for taking pictures of anything

The 50 best photography and camera accessories

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Digital Photographer is the ultimate monthly photography magazine for enthusiasts and pros in today’s digital marketplace.

Every issue readers are treated to interviews with leading expert photographers, cutting-edge imagery, practical shooting advice and the very latest high-end digital news and equipment reviews. The team includes seasoned journalists and passionate photographers such as the Editor Peter Fenech, who are well positioned to bring you authoritative reviews and tutorials on cameras, lenses, lighting, gimbals and more.

Whether you’re a part-time amateur or a full-time pro, Digital Photographer aims to challenge, motivate and inspire you to take your best shot and get the most out of your kit, whether you’re a hobbyist or a seasoned shooter.