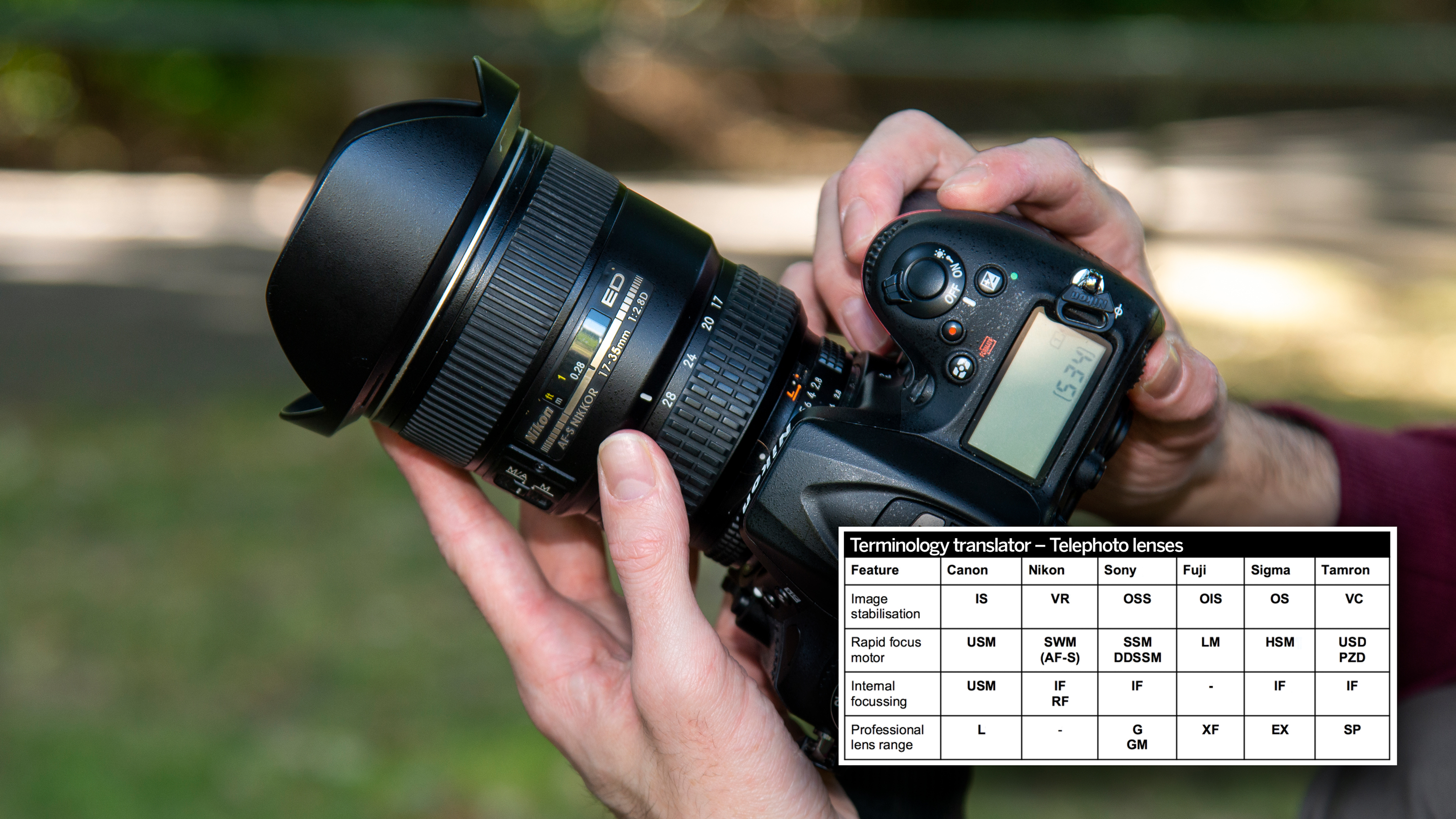

Photography cheat sheet: lens terminology translator

Bust through the technical jargon with these cross-manufacturer guides – they'll help you understand what you're getting in a lens

Understanding the technology present in a lens is essential for making informed decisions about which models you need in your kitbag. As with most photographic equipment, there are times when you will find that a feature does not offer a significant-enough advantage to justify the financial outlay, while in other circumstances it may be almost impossible to create the images you need without a certain piece of kit.

With photographic lenses the presence of such features may not be indicated as obviously as by having a physical switch, for example lens coatings or internal mechanisms. Often features will be denoted by prefixes or suffixes in the lens nomenclature – those letters and numbers that make up the often unwieldy and confusing lens names.

Read more: photography cheat sheet: jargon-busting lens glossary

This can make lenses seem like an obscure and intimidating area of the market, but they're really not! Here we’ll take an in-depth look at lens technology and the terms that are commonly used to indicate its inclusion. We haven't got every single lens manufacturer here, but have tried to cover the most common.

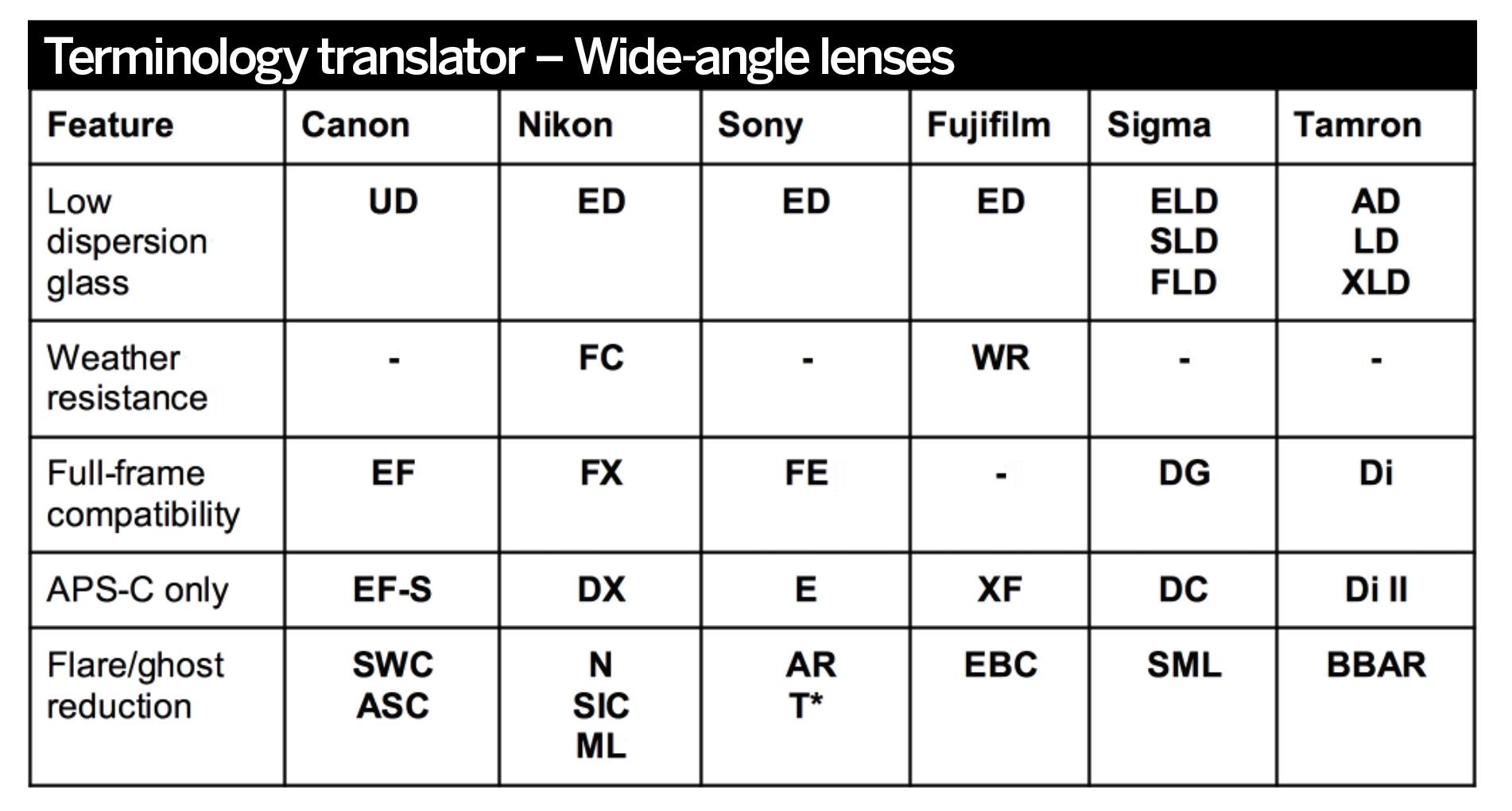

Wide-angle lenses

Wide-angle lenses are generally accepted to be optics with a focal length of less than approximately 40mm, and today they cover everything down to 10mm for APS-C camera models and around 12mm for full-frame sensors. These are the optics of choice for professional landscape and travel photographers, but they find a use in a wide range of shooting scenarios, from environmental portraiture to sports.

In some respects it is in this range of optics that naming conventions have the most potential to confuse buyers. This is because, as digital photography developed, there was a division between lenses that were needed for wide-angle photography on digital models, and those that were capable of being brought over from film systems.

Due to the smaller sensor area of early digital cameras and the APS-C models available today, the multiplication factor applied to the focal length of mounted lenses means that wider than usual settings are needed to produce truly wide-angle perspectives. The optical designs required to enable this to happen, however, mean that standard full-frame compatible lenses would be prohibitively large, heavy and expensive to manufacture. The solution has been to produce lines of digital-only lenses, with smaller image circles to cover the smaller sensor formats. This enables reduced focal lengths without enormous element diameters.

It is important to recognize which lenses are available for use on both crop-frame and 24x36mm format sensors. While there are now telephoto lenses with smaller image circles, this is usually for weight and portability benefits in mirrorless camera systems.

Other key features of wide-angle lenses are those that address the optical challenges of wide perspectives. These include chemical coatings and glass element designs to reduce edge fringing and geometric distortions, among other things. Designations to look out for are ASPH, which indicates the use of aspherical elements for reduced distortion, and ED or ULD, which denotes special low-dispersion glass. These lens elements are designed to more effectively focus light of different colours at the same point, thereby reducing chromatic aberration.

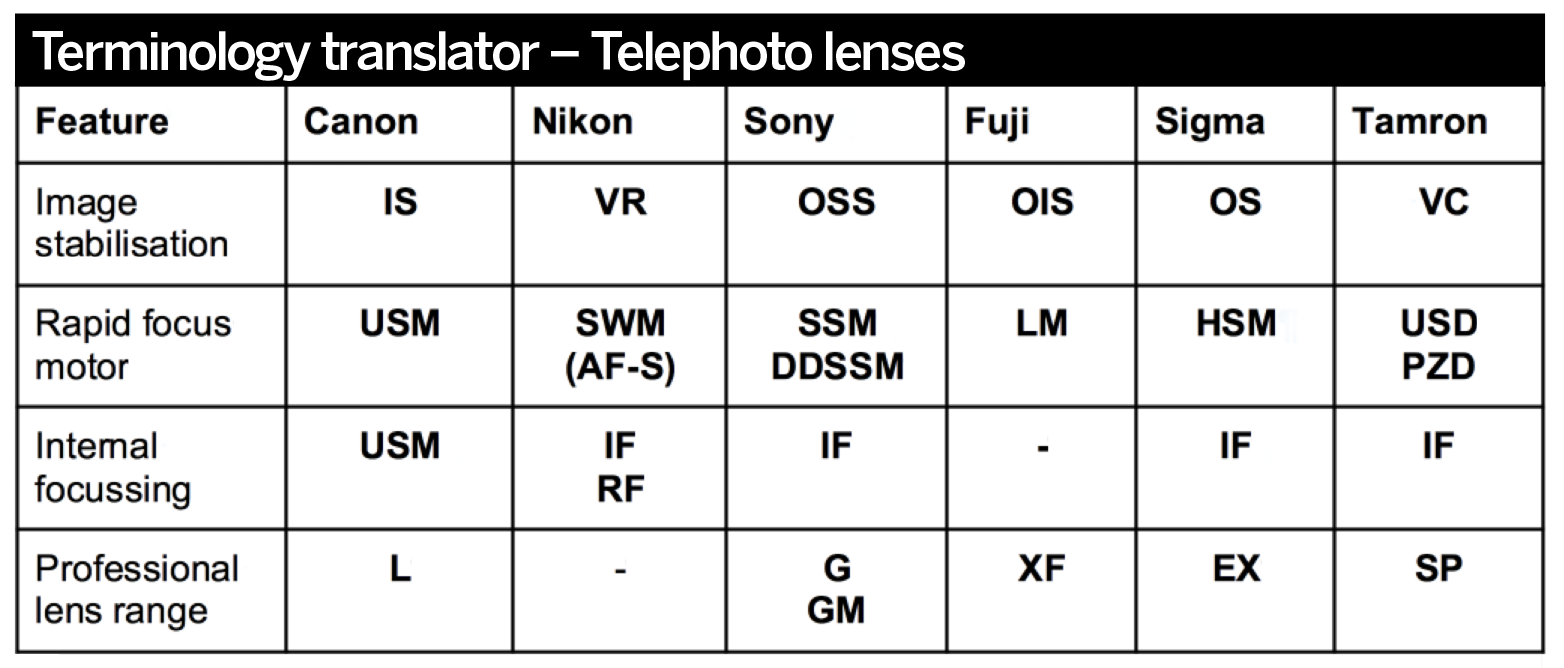

Telephoto lenses

Just as ultra-wide lenses are required for stretched perspectives, frame-filling shots of far-off subjects cannot be achieved without the use of telephoto optics. Whether you select a long telephoto prime lens, such as a 500mm f/4, or a telephoto zoom, like a 70-300mm f/4-5.6, these models enable the photographer to refine their composition precisely, cropping out unwanted environmental detail.

These lenses are usually the choice of wildlife and sports photographers – most notably models with focal lengths of above 300mm. For this reason the features incorporated into telephotos are usually geared towards allowing rapid work – quickly achieving focus and enabling near-instantaneous recomposition.

Due to the higher magnification, camera shake is also a far greater probability when using telephoto optics, so professional models almost always make use of image stabilization technology. This makes handheld shooting in lower ambient lighting a possibility, by varying the position of specialized lens elements to counteract camera shift. The effectiveness of this system varies from lens to lens, although most contemporary stabilizers enable up to three stops of shake reduction as a minimum.

On more advanced lenses you will find additional speed-beneficial features, such as supersonic wave autofocus motors, internal and rear-focusing mechanisms, and the ability to apply manual focus adjustments at any time, even if AF is active. While these may not be worth the extra investment if you rarely shoot in extremely fast-moving scenarios, for working pros and advanced enthusiasts they can mean the difference between grabbing a shot and missing a winning opportunity.

Read more

The best lens for portraits

The best professional cameras

The best Canon lenses

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Digital Photographer is the ultimate monthly photography magazine for enthusiasts and pros in today’s digital marketplace.

Every issue readers are treated to interviews with leading expert photographers, cutting-edge imagery, practical shooting advice and the very latest high-end digital news and equipment reviews. The team includes seasoned journalists and passionate photographers such as the Editor Peter Fenech, who are well positioned to bring you authoritative reviews and tutorials on cameras, lenses, lighting, gimbals and more.

Whether you’re a part-time amateur or a full-time pro, Digital Photographer aims to challenge, motivate and inspire you to take your best shot and get the most out of your kit, whether you’re a hobbyist or a seasoned shooter.