Virtual Photography: taking photos in videogames is imaging's next evolution

Virtual photography is a growing movement of taking photos in videogames. The head of GamerGram tells us more…

Photography is a unique industry. It is at once the product of science and the byproduct of art. It is simultaneously a community that’s enthralled by what is new, yet appalled by what is different. And it is at once experiencing the greatest popularity it has ever seen, and the greatest depression it has ever witnessed.

There are those who retreat further and further towards the old analog ways, shooting on film with “real” cameras that possess no electronics whatsoever. And there are those who embrace photography’s most ultramodern aspects, including software-driven smartphones that purists often decry it as the death of the art form.

Meanwhile there are those who have discovered, or rediscovered, a love of that art form in via the increasingly popular movement of virtual photography – a modern evolution of the craft often dismissed as not “real” art, not “real” photography.

It’s a familiar refrain. It wasn’t long ago that digital cameras were accused of the same thing by 35mm users, just as 35mm was by large format users before that. And all the while, the photographers using the latest tech are as “real” as they ever were.

“Most of our followers are photographers in the real world,” explains Alex Coley, founder of GamerGram – a budding online portal for virtual photographers. “They’re bringing those skills they learn outside into these gaming worlds, and they apply the skills and get beautiful shots like these.”

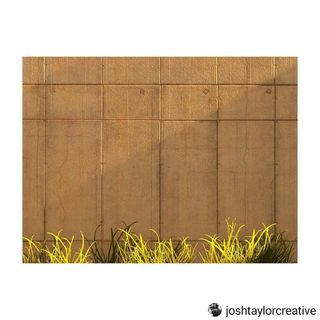

The photographs themselves are inarguably beautiful, inarguably possessed of artistic merit, and inarguably the result of genuine photographic technique and discipline. In the bespoke ‘photos modes’ specially coded into certain videogames, you can do everything from change your focal length to choose lenses based on how much chromatic aberration they exhibit.

“It mainly started off as [gamers] taking simple screenshots, uploading them to the internet via different social medias,” recounts Coley, “and I think game developers noticed how big that was becoming so they started creating these photo modes built into their games with basically all the same settings as you’d get in a DSLR camera, but without the lens – that’s the only difference I can really see with the tech.”

Get the Digital Camera World Newsletter

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

It’s worth reiterating the fact that videogame developers are actively investing in virtual photography. Titles like Grand Theft Auto V and Red Dead Redemption 2 cost in the region of $200 million apiece to make, but developer Rockstar Games sees sufficient demand for (and value in) the art form that it devotes a sizable part of that budget to creating a photo mode.

“And putting these photo modes into their games, they’ve realized how much more time people are spending in them, compared to games without photo modes.” When an industry the size of videogames – which is worth more than the music industry and movie industry combined – sees value in something, you cannot simply dismiss it out of hand.

Nor can you account for how a different medium can evolve the art form. Ubisoft’s acclaimed Assassin’s Creed titles – a series of historically situated games that span everything from ancient Egypt to Victorian London – have been famously described as ‘historical tourism’ by the videogames press, for the way they enable players to experience historically accurate recreations of places and people.

“In Assassin’s Creed Origins, you can take tours throughout the whole of Egypt, and there’s a voiceover explaining what [you’re seeing in] the game, where they got their inspiration from. This is all real – this is like a history lesson as you’re walking through.”

The potential for historical photography is utterly unique; who wouldn’t want to wait for the in-game sun to rise, so you can shoot golden hour landscapes of the Pyramids, blue hour images of the Acropolis, or candid street photography along the Via Sacra? “It’s like a one-to-one tourist experience,” says Coley, smiling that it’s also great just being able to take photos of present-day landmarks like the Eiffel Tower without tourists getting in the way.

Virtual photography, then, isn’t some haphazard thing that just happens – no more than real-life photographs in the real world do. Specific locations in specific games have to be scouted and searched, just like non-virtual shooting locations.

“Most of our followers they’re not really playing the game for the story,” Coley states. “If they have a passion for photography, they’re in the game worlds looking for these beautiful photo opportunities, beautiful parts of the game that nobody else has seen.”

Virtual photographers have sizeable followings online, just like traditional photographers do, and they even have their own specialisms. Just as there are astrophotographers and landscape photographers and wildlife photographers in real life, there are equivalents in the digital realm.

“We’ve got people who like space worlds, people who are dedicated to trees, we’ve got people who are dedicated to animals,” agrees Coley, “basically everything you can think of in real-world photography is portrayed into virtual photography. Because as I say, most of our followers are photographers in the real world anyway.”

As ultra-niche as the art form – and these sub-genres within it – may appear, some of the bigger names are finding commercial recognition from their photographic specialisms.

“We have this guy here called mr.hasgaha – he takes photos of Star Citizen, and that’s the only real game he plays and takes images of. But the developer, Robert Space Industries, actually use his images to promote their game online. So he’s building a name for himself, he’s doing really well.”

The ability to photograph bygone historical eras and exotic extraterrestrial locations isn’t the only allure of virtual photography. Far from being a juvenile pursuit, it provides a legitimate outlet for disabled photographers who are no longer physically able to get out and explore – or perhaps even able to operate a camera – to enjoy their pursuit of picture-taking.

“We’ve seen quite a lot of that, a lot of disabled people seem to enjoy these worlds because it’s somewhere they can get around and see new things.”

Coley’s vision with GamerGram is to provide a centralized showcase-come-portfolio for virtual photographers to collect and share their work, where the art form can be appreciated and discovered.

“Our end goal is to have our own app. That’s something that I can’t fund myself at the moment, and I’m trying to get awareness that this is a thing. We want an app dedicated to virtual photography – and we want it to be like the LinkedIn of virtual photography.

“All our virtual photographers are spread across social media, so they’ve got all these different accounts all over the place. In our app we would like them to not only upload their own images, but to drop their links from all over the internet – so someone could just go to our app, find a specific person they like, look at their images, and also click on their links to Instagram, Flickr, Twitter, where they can look at their past work as well.”

It seems so alien, and so non-traditional, that many photographers might look past it – just as they looked past the legitimacy of camera phones, which are now far more relevant to modern photography than ‘proper’ cameras are. And virtual photography only seems destined to become bigger – especially when you consider the inevitable convergence of technologies such as VR glasses.

“I was talking to somebody yesterday about virtual reality. I mean, the graphics aren’t the best at the moment, but in ten years they’re going to be where these are [motions to the virtual photographs around us]. So you’re going to be looking through the virtual lens, looking up and down and around, crouching down to take images, and press a little button on the side [of your headset] to take a picture.”

It may seem pie in the sky, but it is happening right now. Millions of children are growing up with their first exposure to photography being via their smartphone, and their second exposure being via photo modes in videogames. As those children become older, those experiences will be the new norm.

“It’s like we say here,” concludes Coley, referring to GamerGram’s mission statement. “We have loved being at the forefront of the art form’s growth and we like to think it inspires young gamers to pick up a camera in the real world. And I think it does.”

And so do we. Follow GamerGram for the latest developments in virtual photography on Instagram and Twitter.

Read more:

The Matterport 3D VR system is like Google Street View for your house

Insta360 Evo review

The best tablets for photo editing and photographers in 2019

James has 22 years experience as a journalist, serving as editor of Digital Camera World for 6 of them. He started working in the photography industry in 2014, product testing and shooting ad campaigns for Olympus, as well as clients like Aston Martin Racing, Elinchrom and L'Oréal. An Olympus / OM System, Canon and Hasselblad shooter, he has a wealth of knowledge on cameras of all makes – and he loves instant cameras, too.